Design

Tools

Wendy Mackay & Michel Beaudouin-Lafon

Laurent Grisoni, Président

Professeur des universités, Université de Lille 1

Yannick Prié, Rapporteur

Professeur des universités, Université de Nantes

Peter Dalsgaard, Rapporteur

Professeur associé, Université d’Aarhus

Annie Gentes, Examinatrice

Maître de Conférences HDR, Télécom Paris-Tech

Gillian Crampton-Smith, Examinatrice

Professeur Émérite, Univ. de sciences app. de Potsdam

Michel Beaudouin-Lafon, Directeur de thèse

Professeur des universités, Université Paris-Sud

Wendy Mackay, Co-encadrante de thèse

Directrice de Recherche à Inria Saclay

Summary

Mainstream digital graphic design tools seldom evolved since their creation, more than 25 years ago. In recent years, a growing number of designers started questioning the resulting invisibility of design tools in the design process.

In this dissertation, I address the following questions: How do designers work with design software? And how can we design novel design tools that better support designer practices?

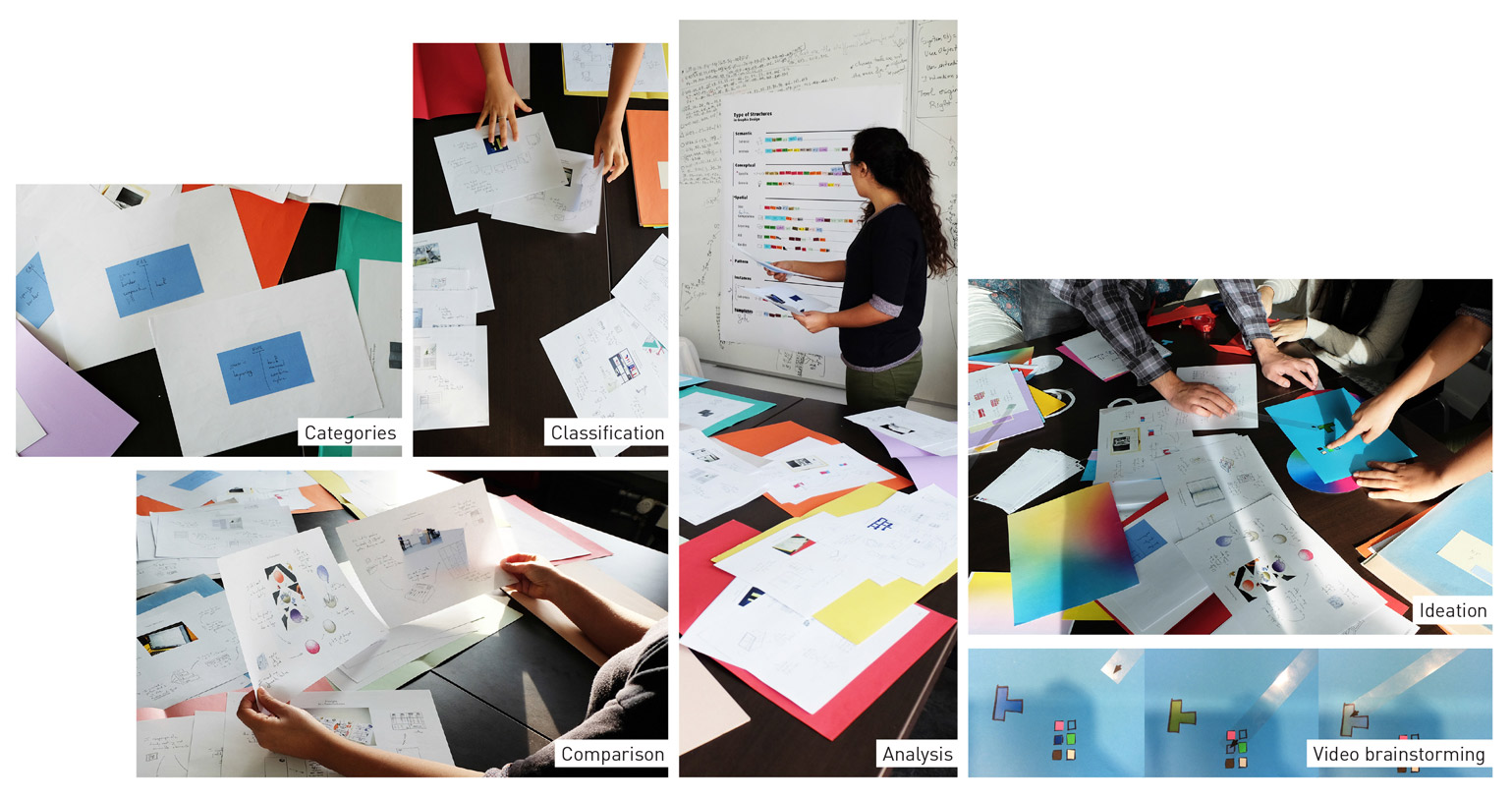

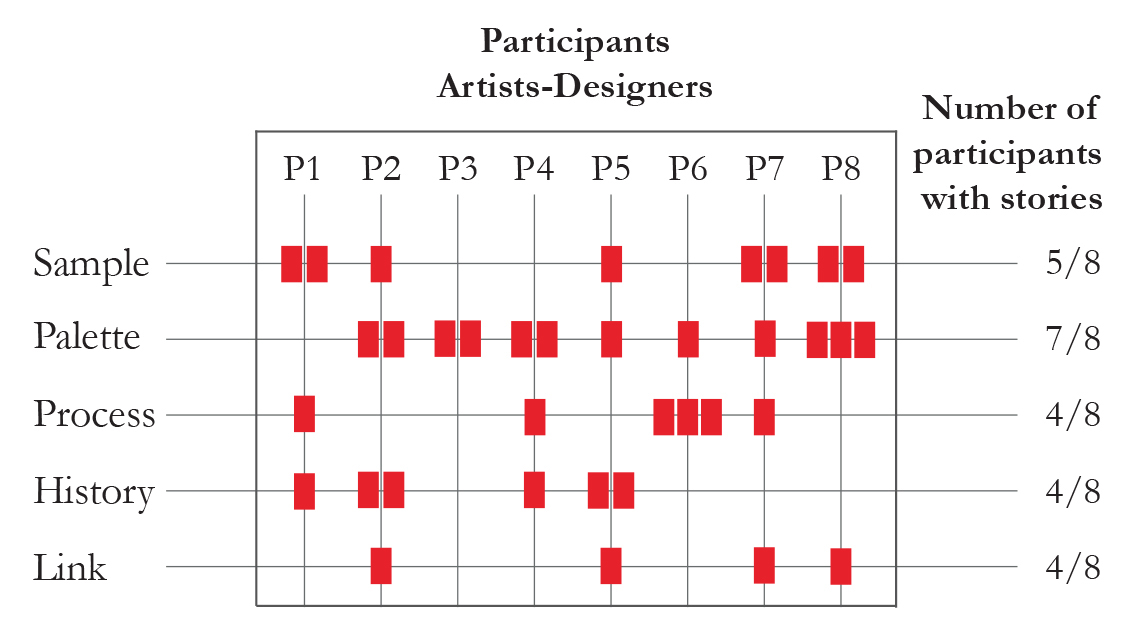

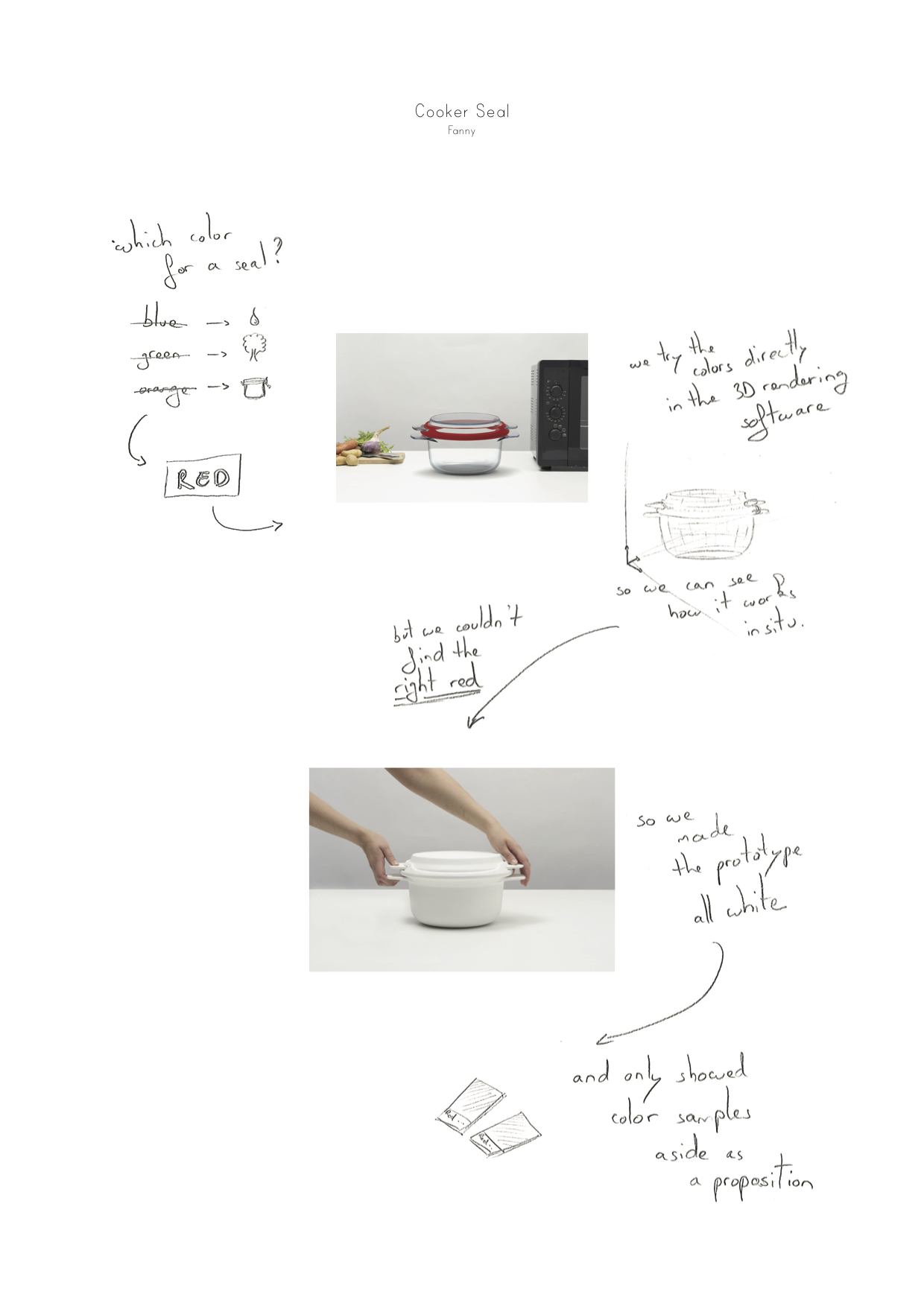

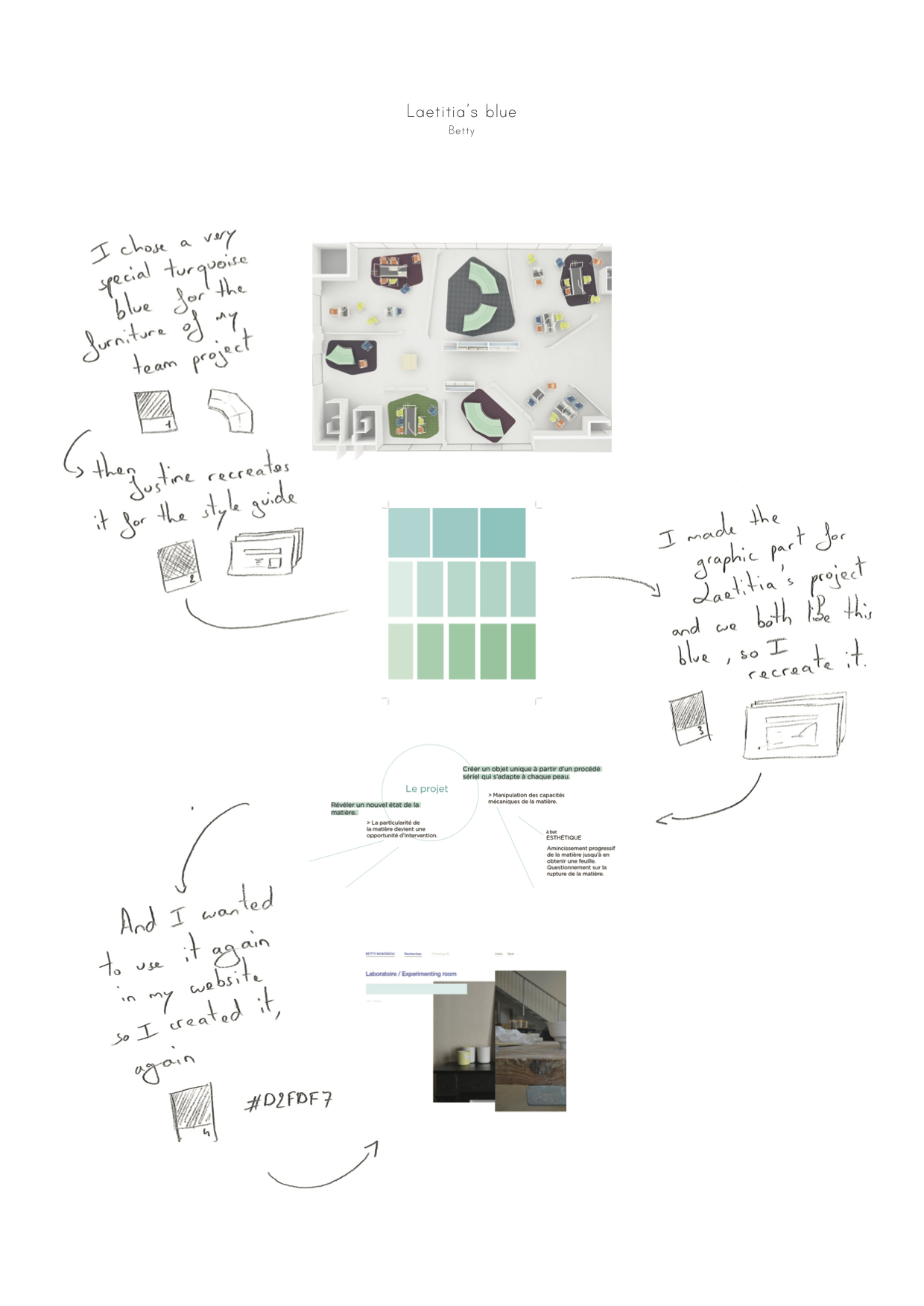

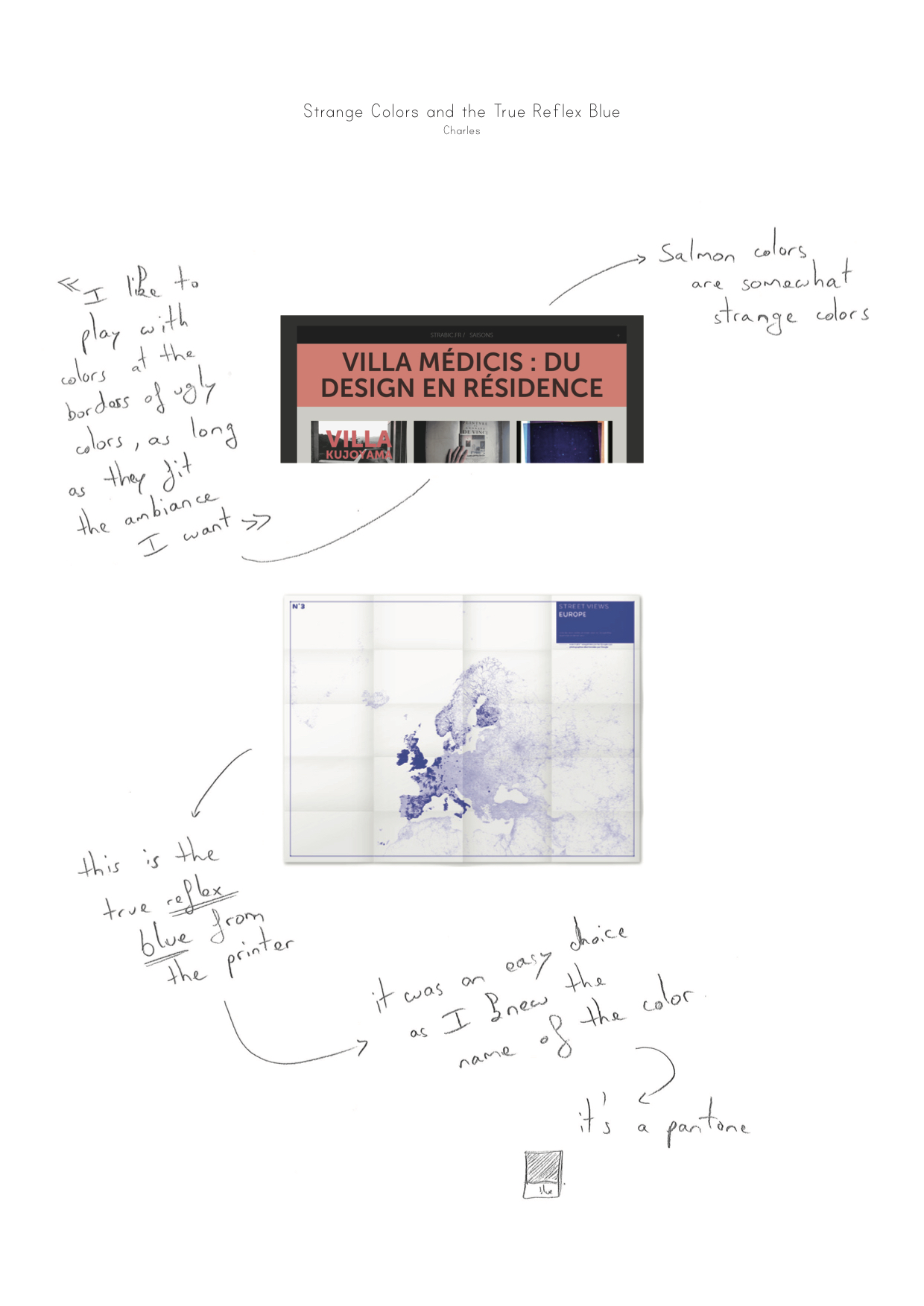

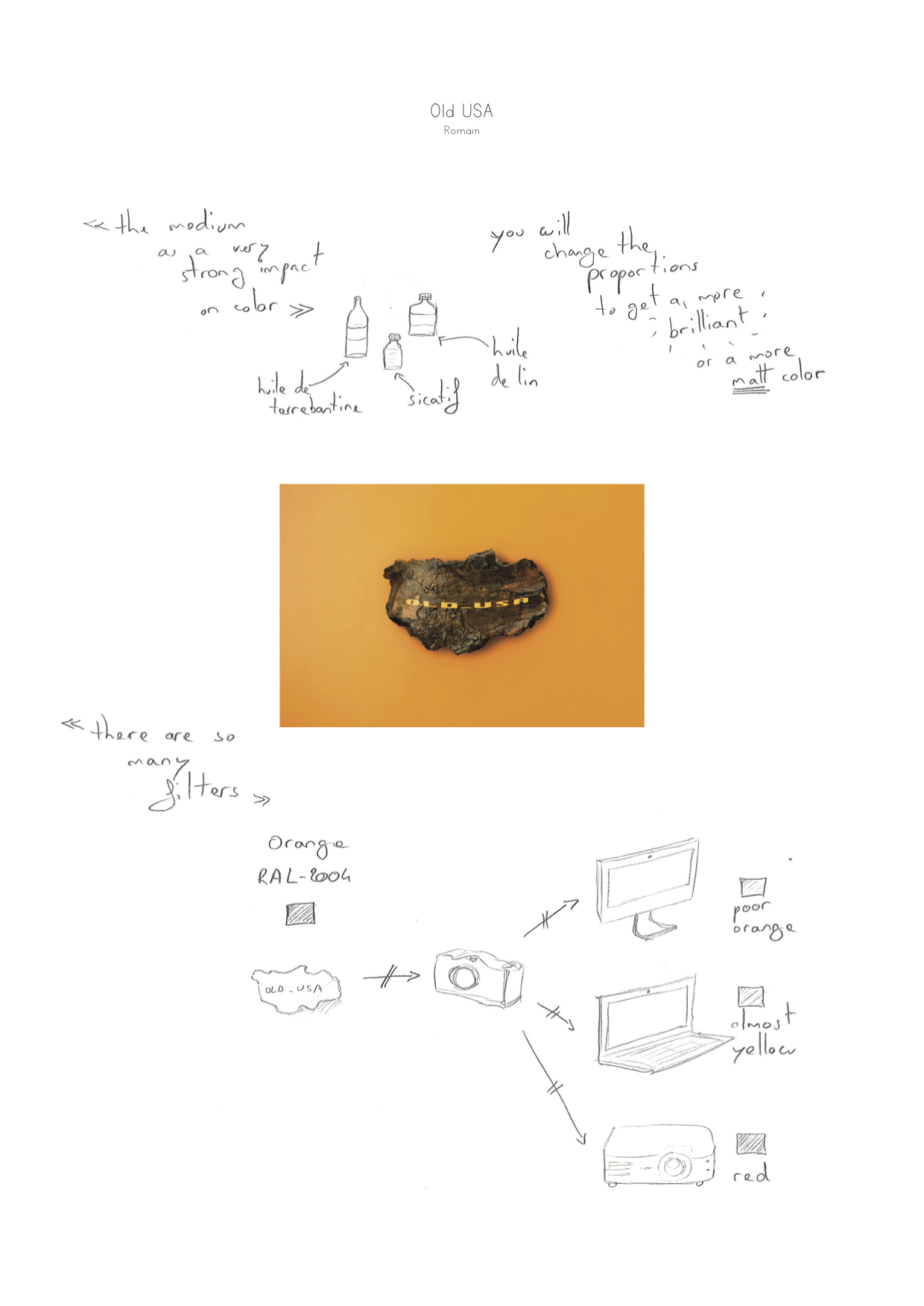

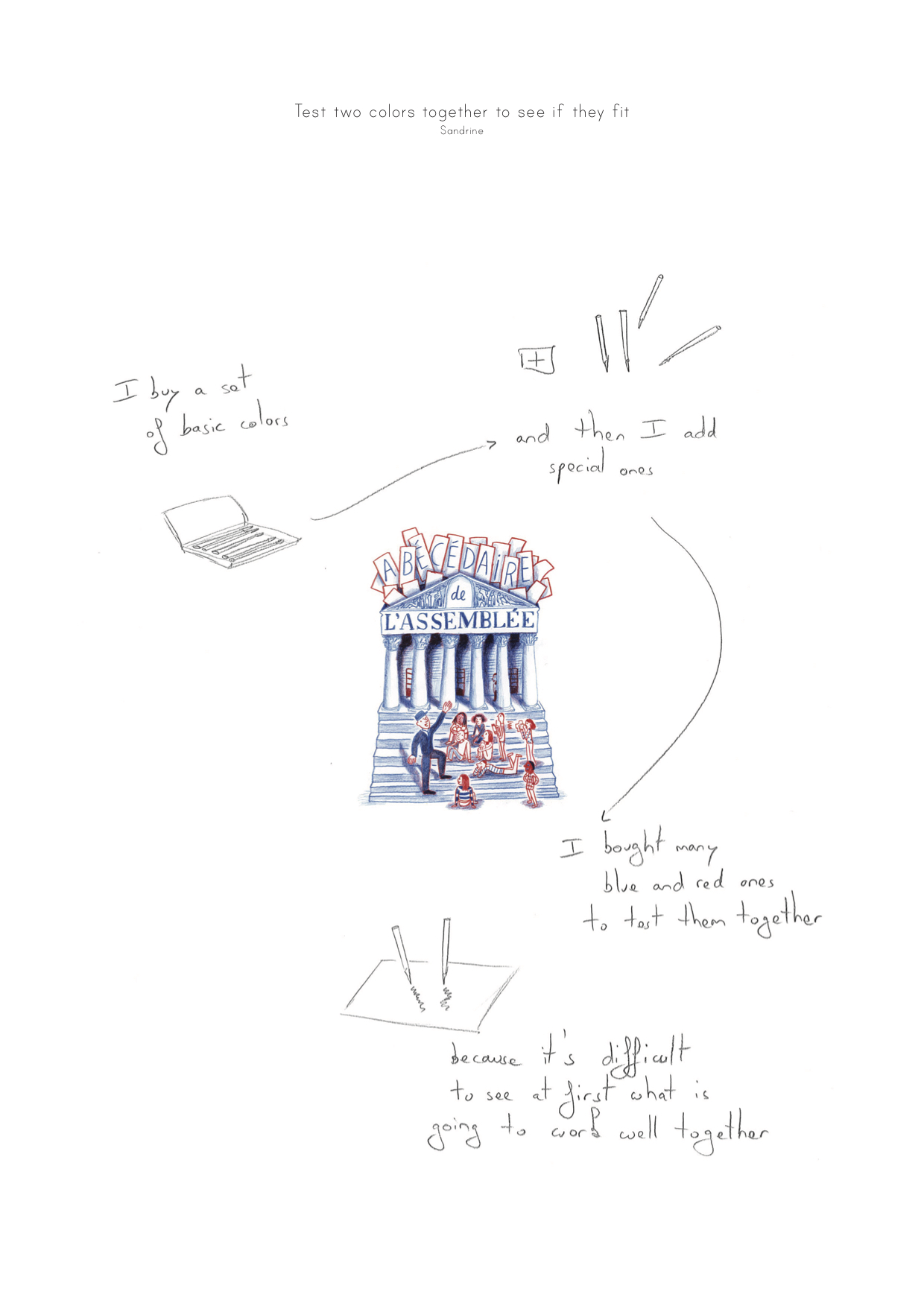

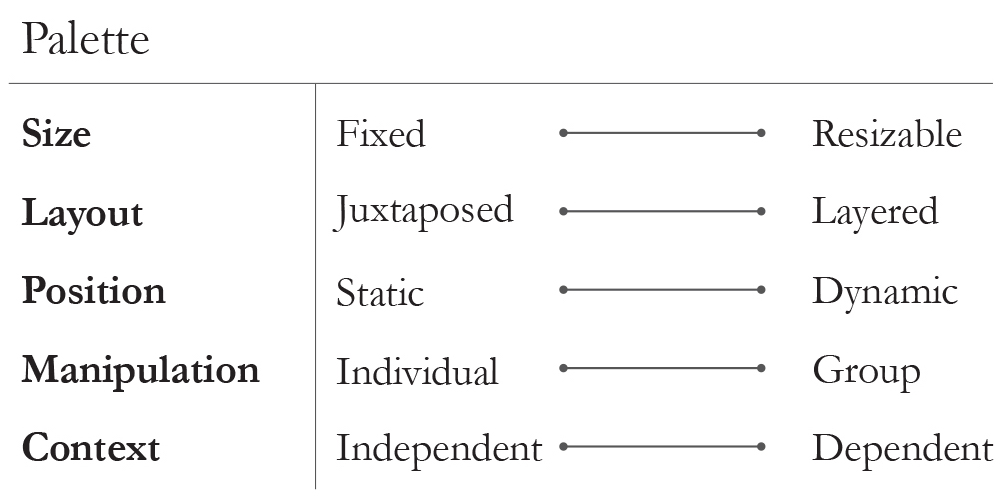

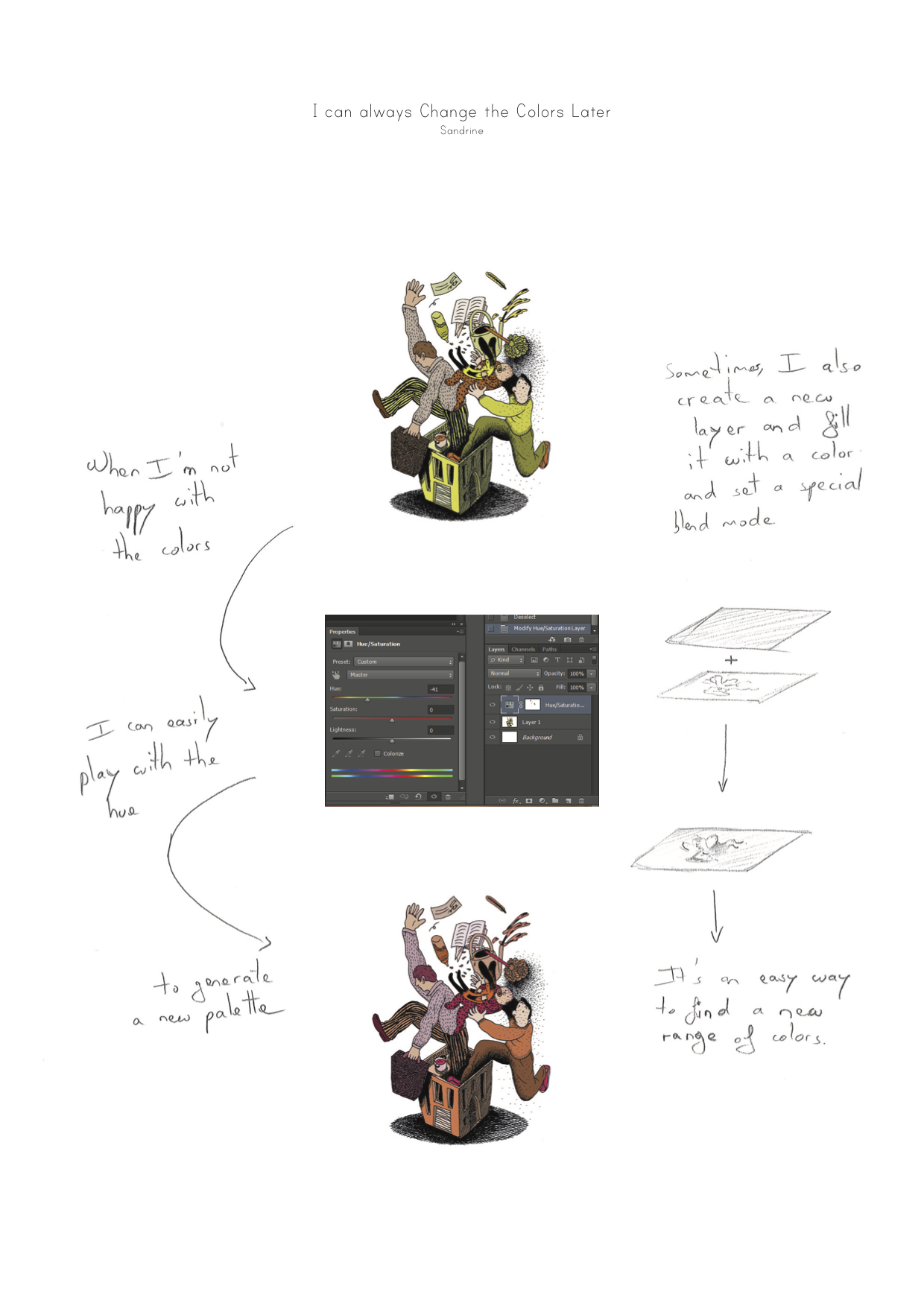

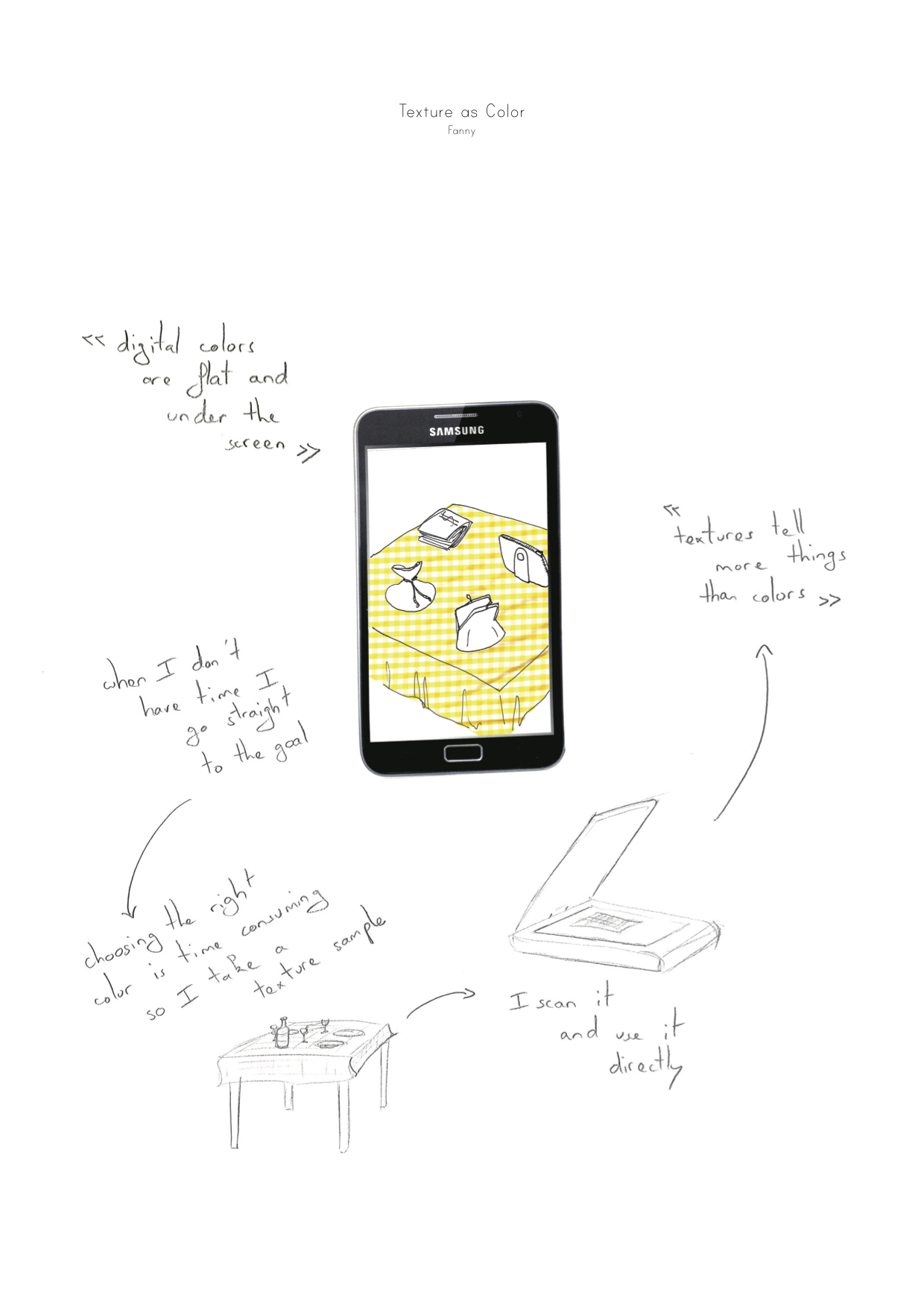

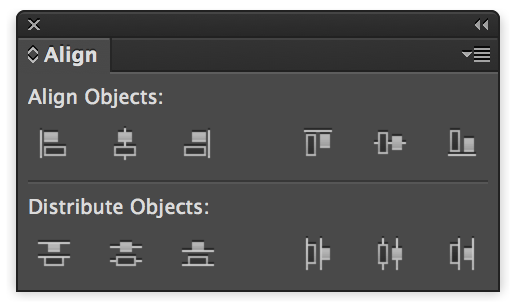

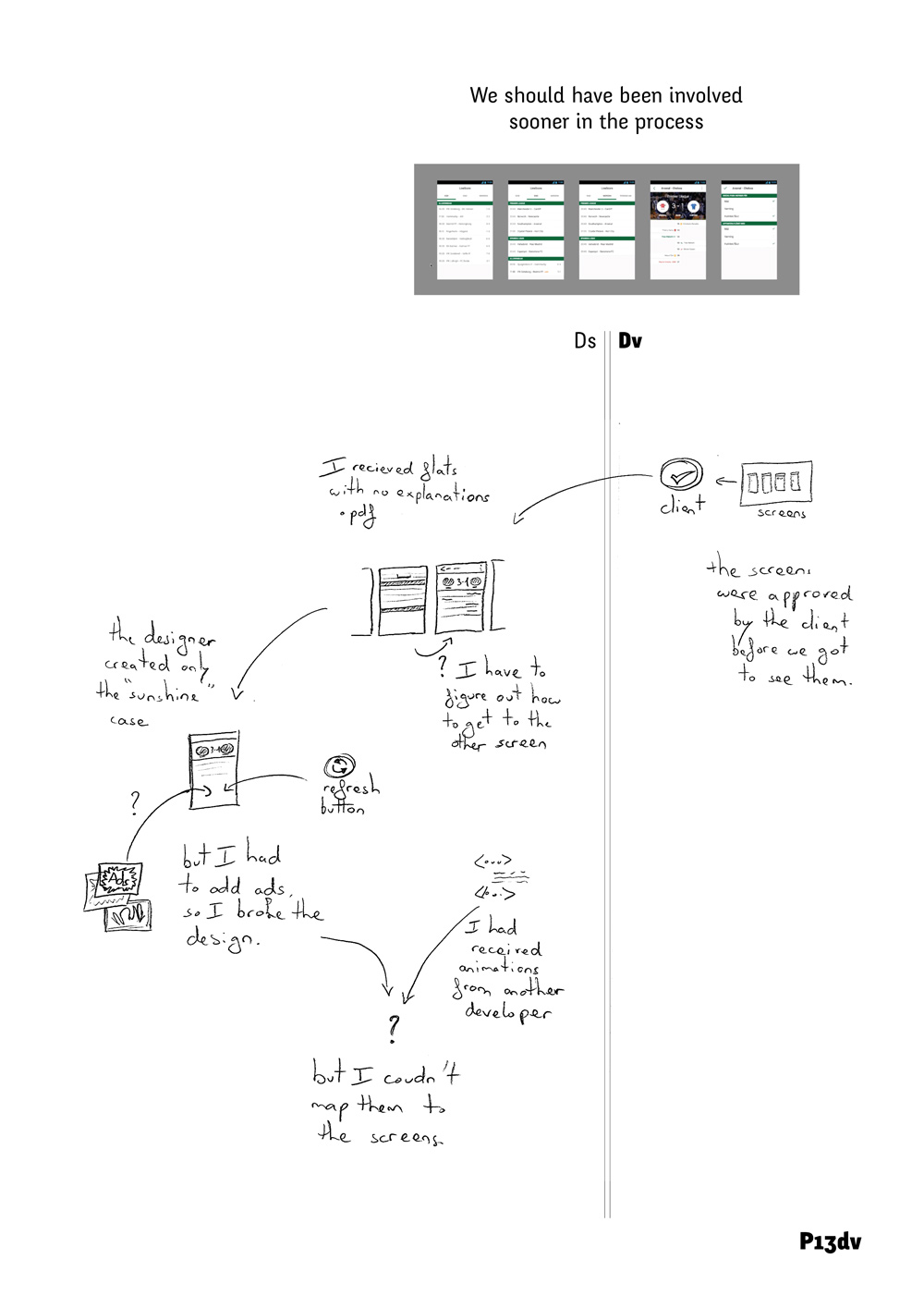

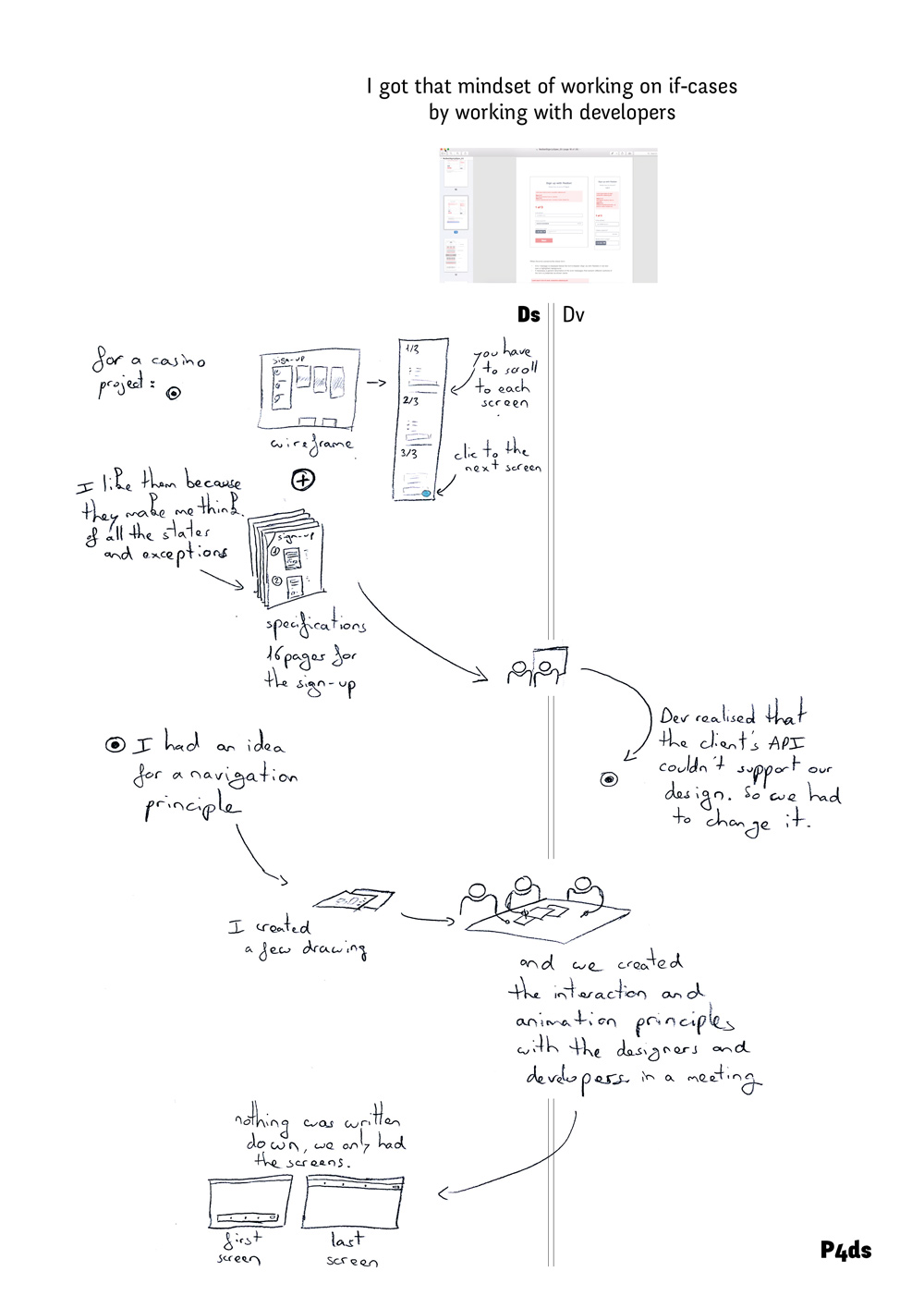

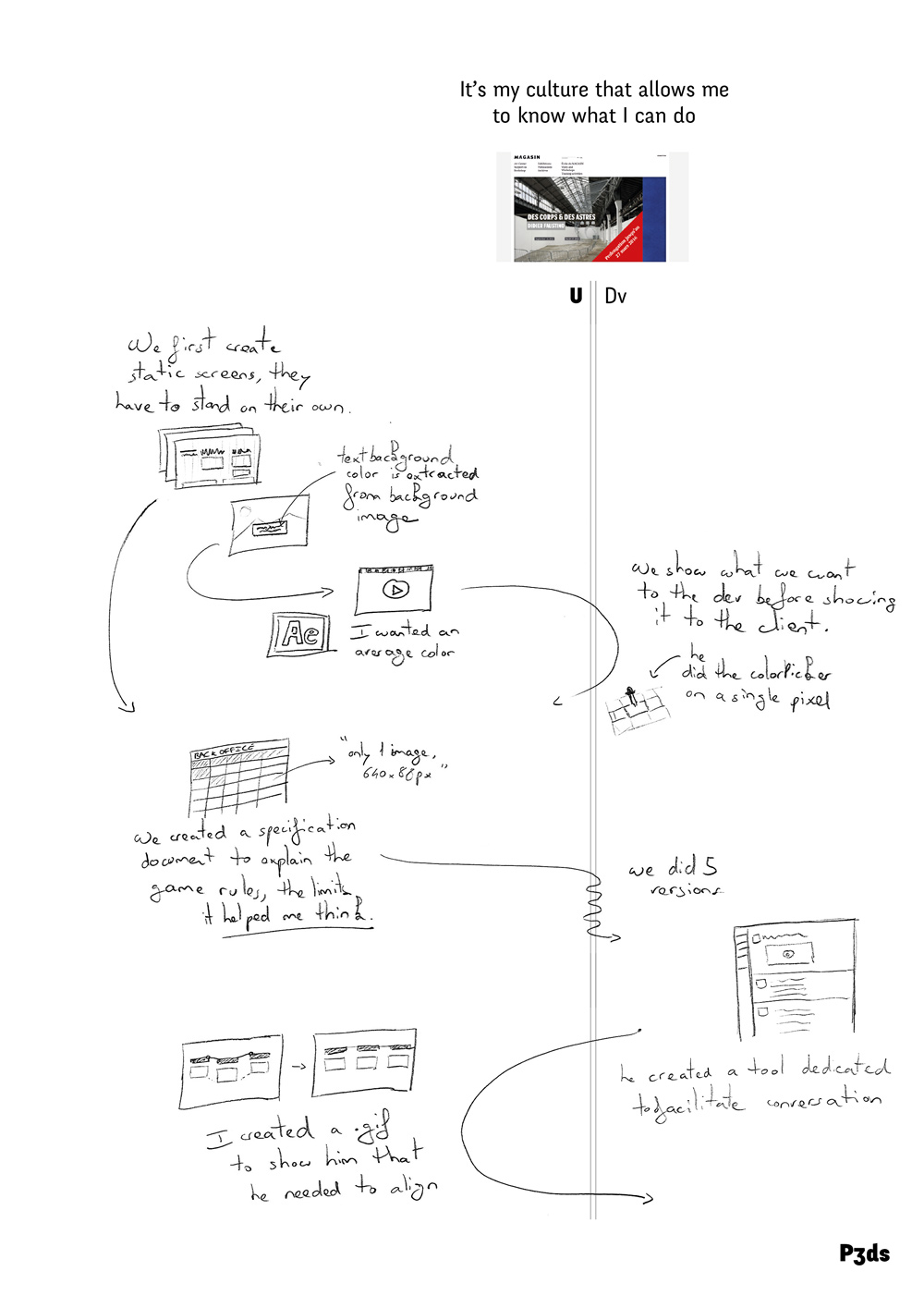

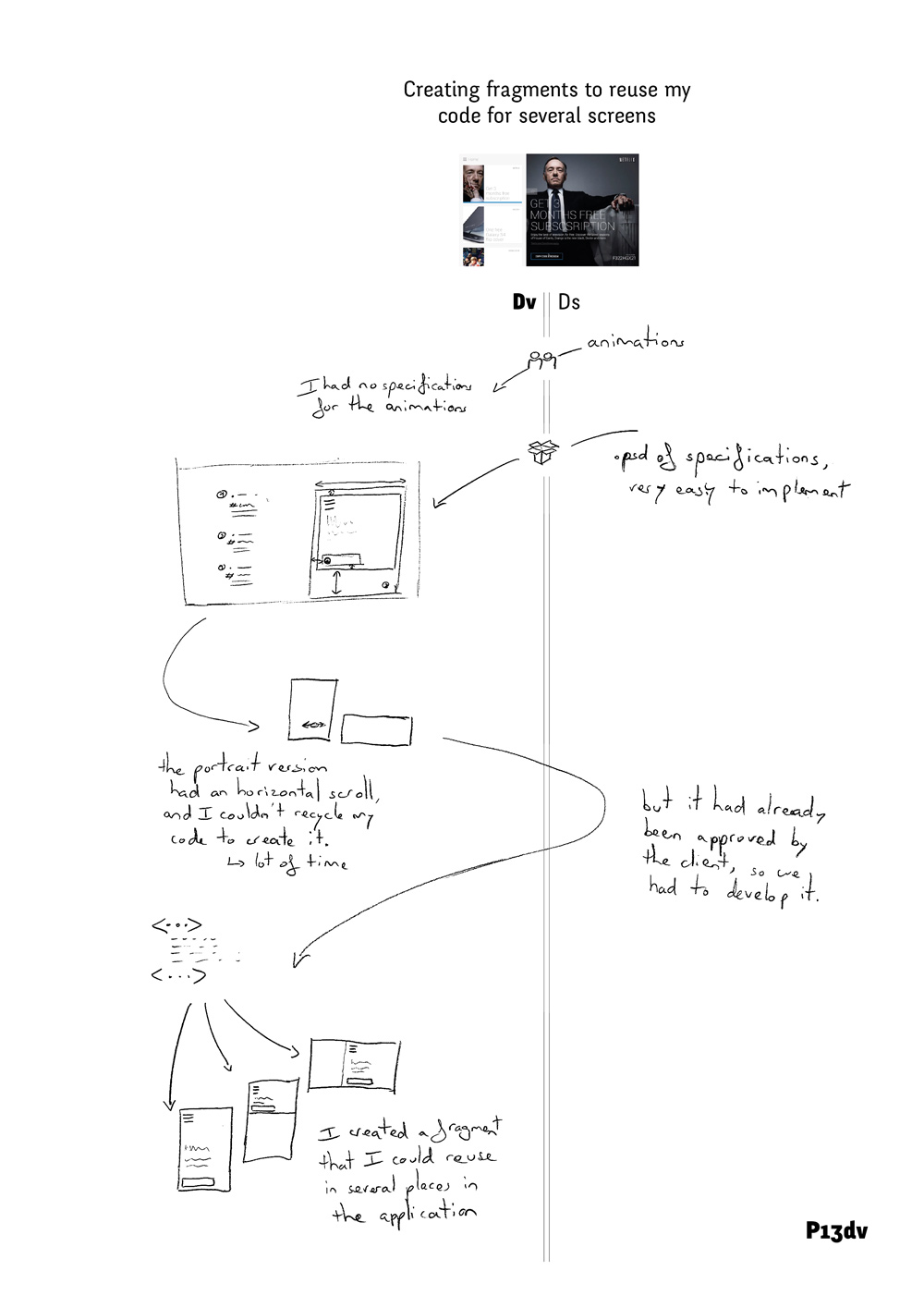

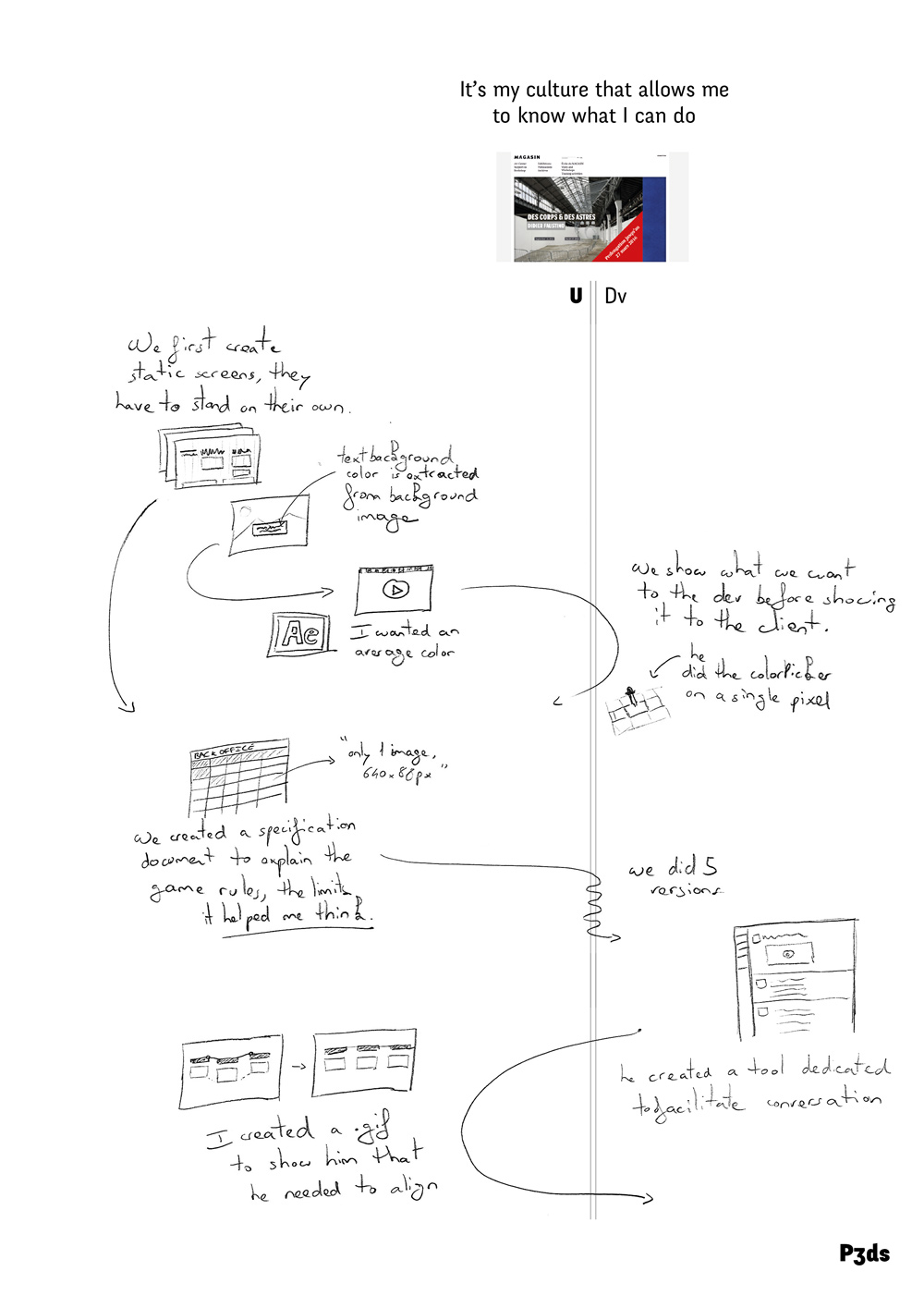

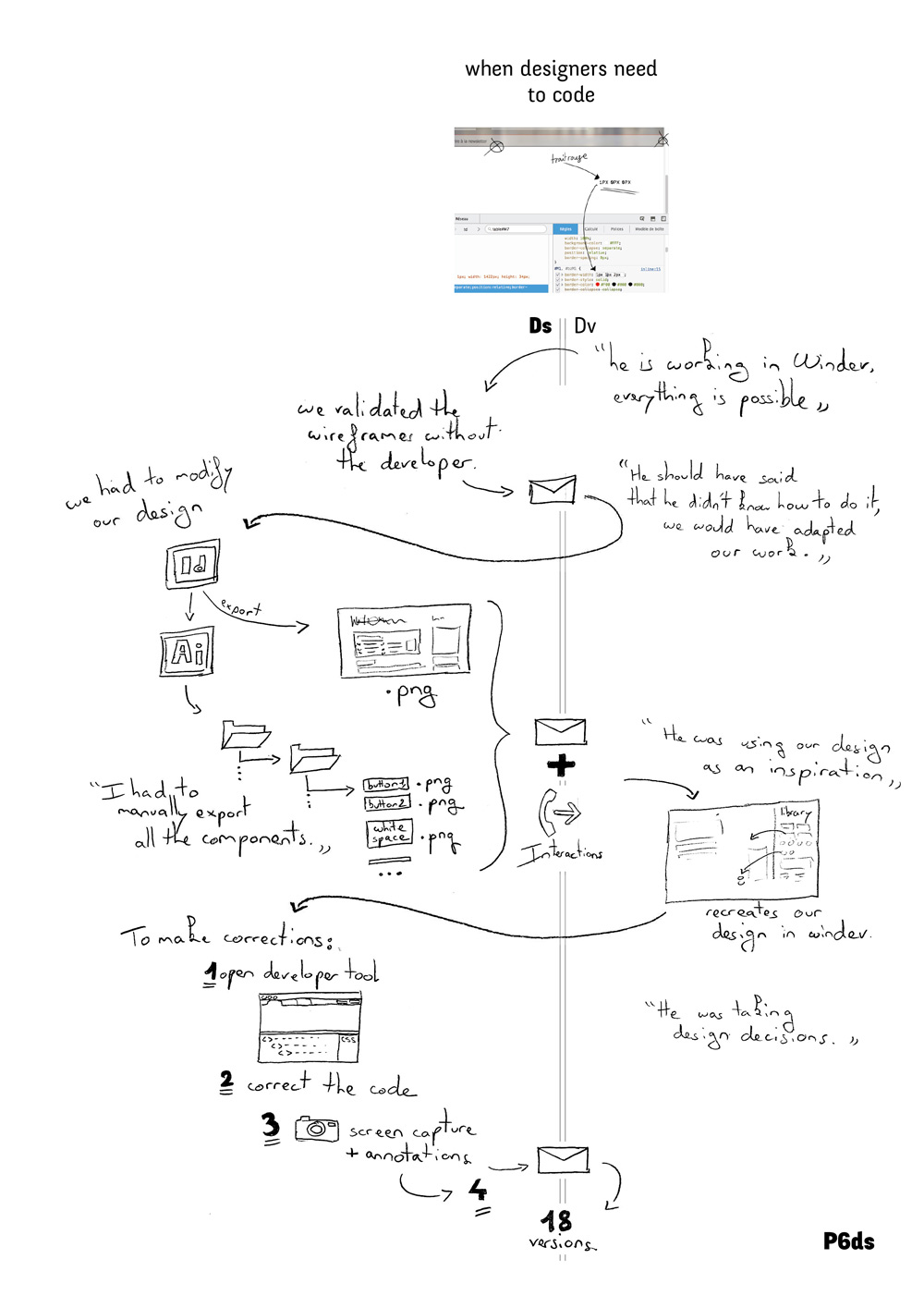

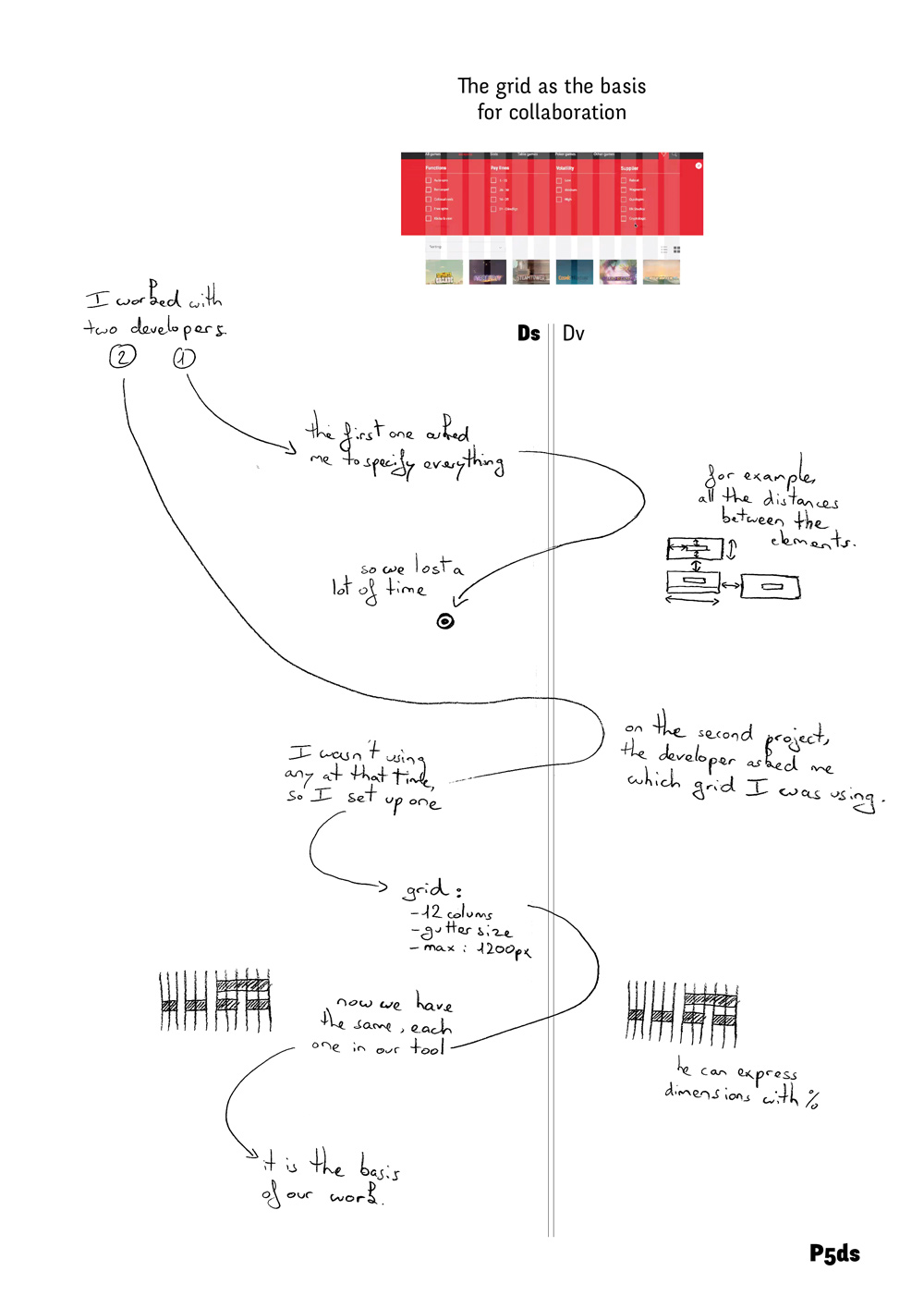

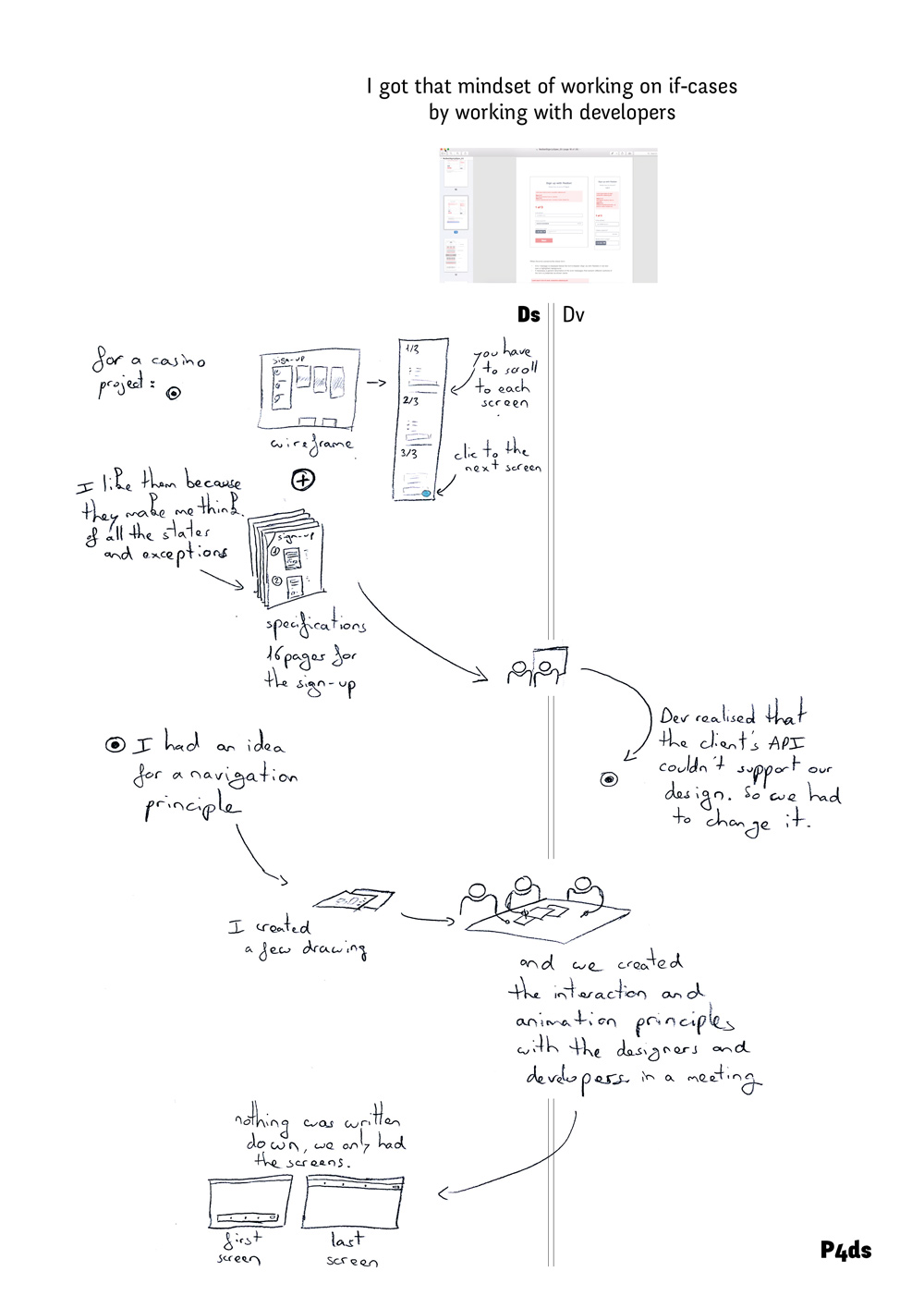

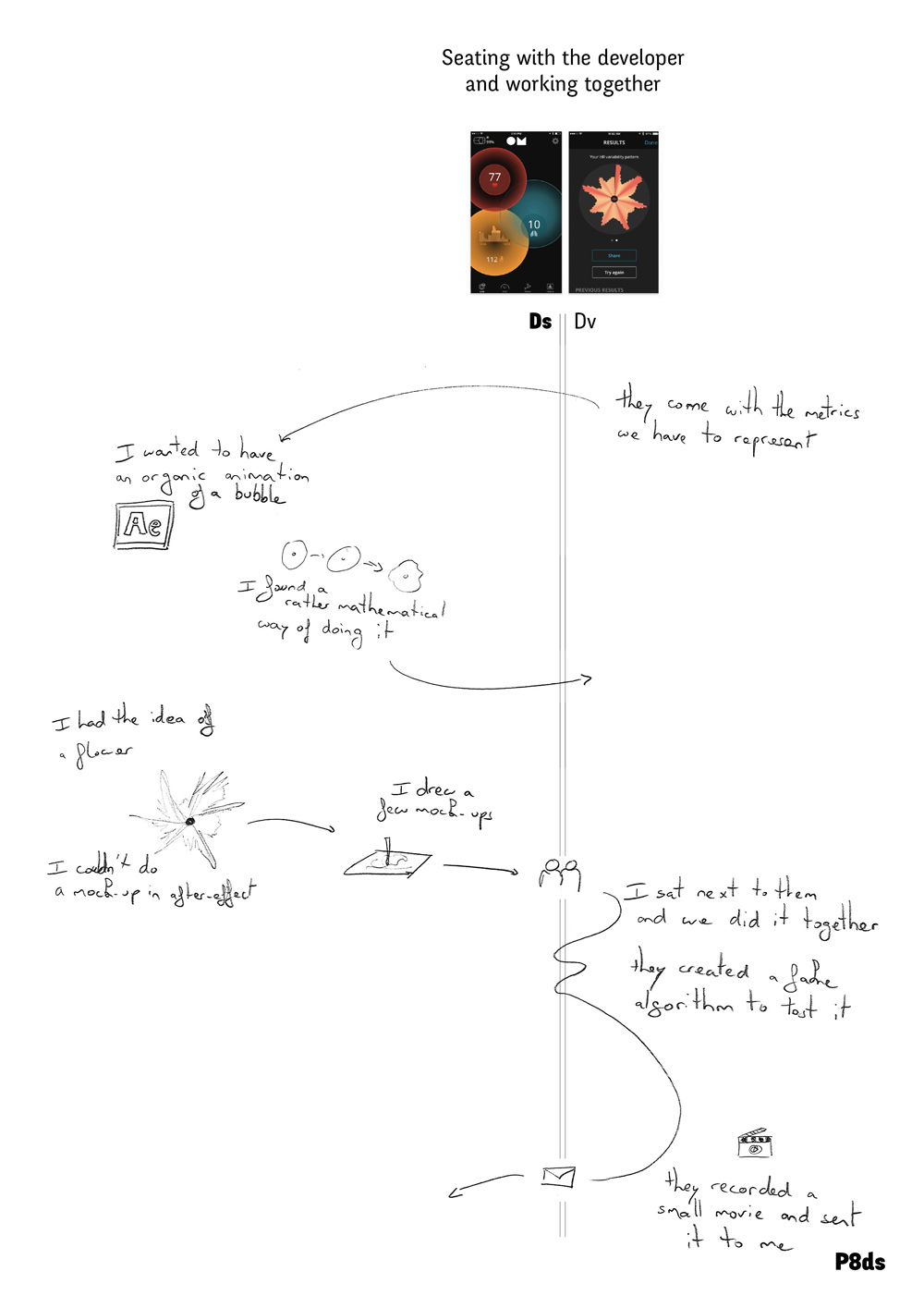

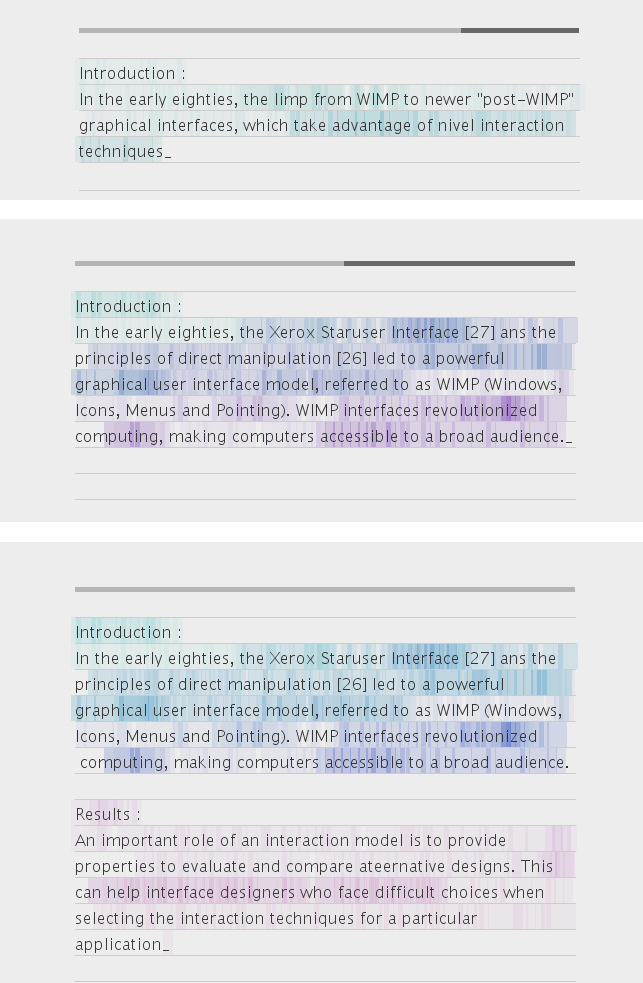

Using StoryPortraits, a method designed to capture rich qualitative insight in a form that supports both analysis and design conversations, I first study four designer practices, ranging from specific design operations such as color selection, alignment and distribution, to more complex endeavors such as layout structuring and collaboration with developers.

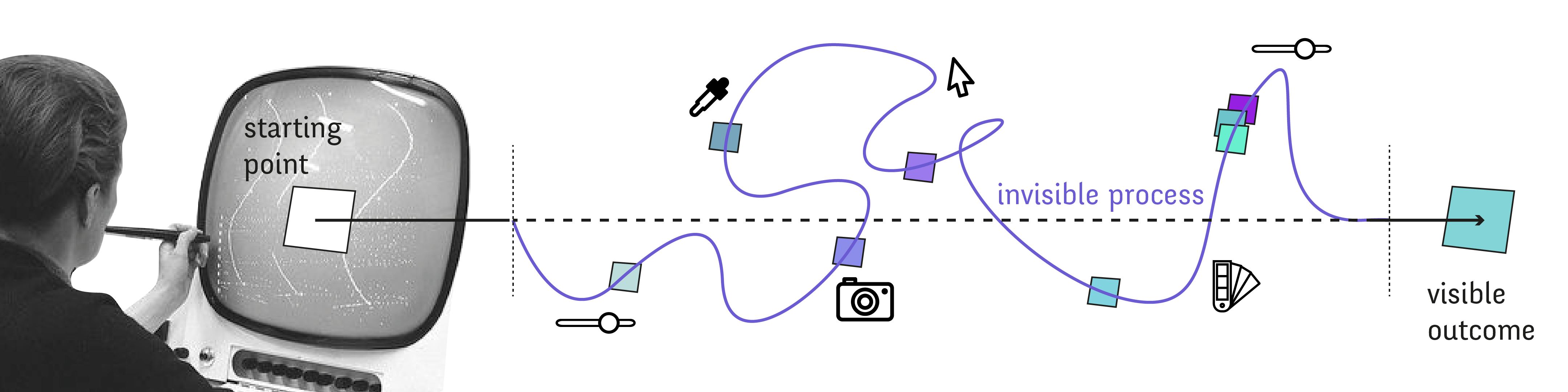

In these empirical studies, I analyze the wealth of designer practices and I characterize the existing mismatch between current digital design tools and designers practices. I show how design tools, because they decouple creativity from tool use, prioritize values such as efficiency and user-friendliness that do not support existing creative practices.

Facing this mismatch, designers need to resort to programming to benefit from the computational power they can't access with traditional tools.

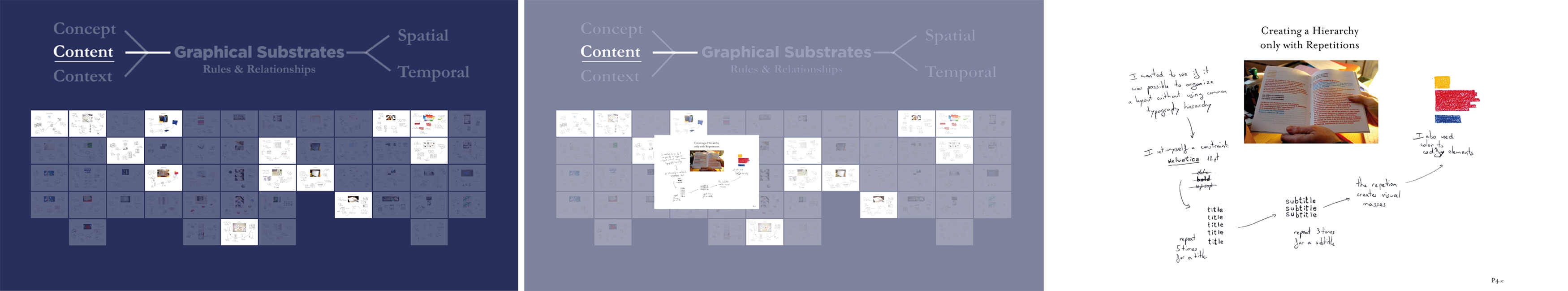

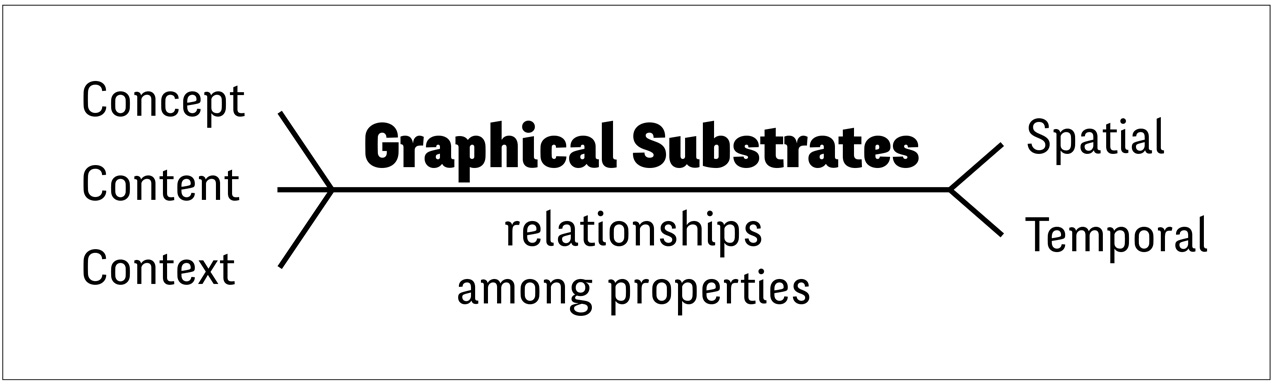

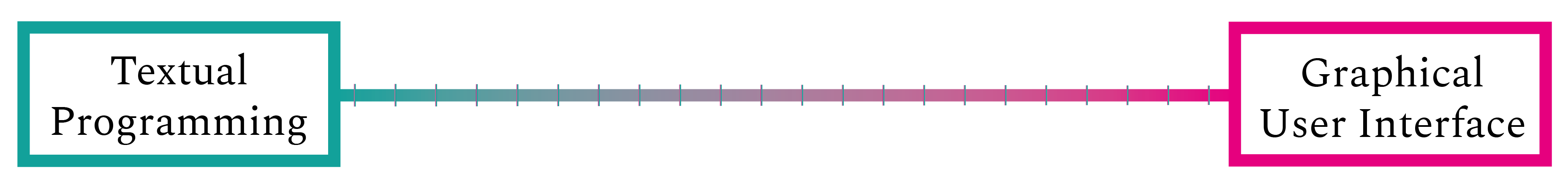

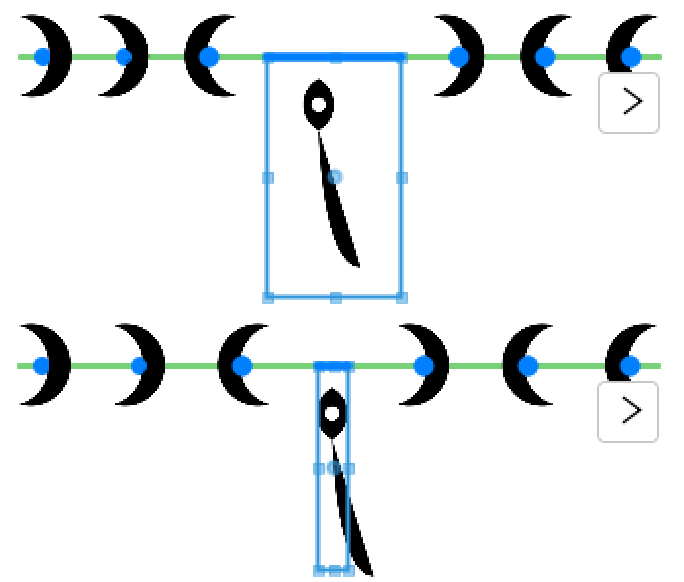

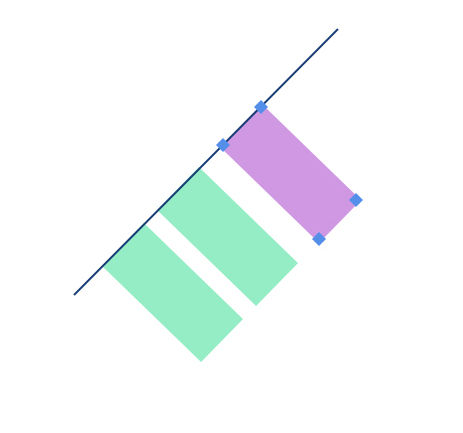

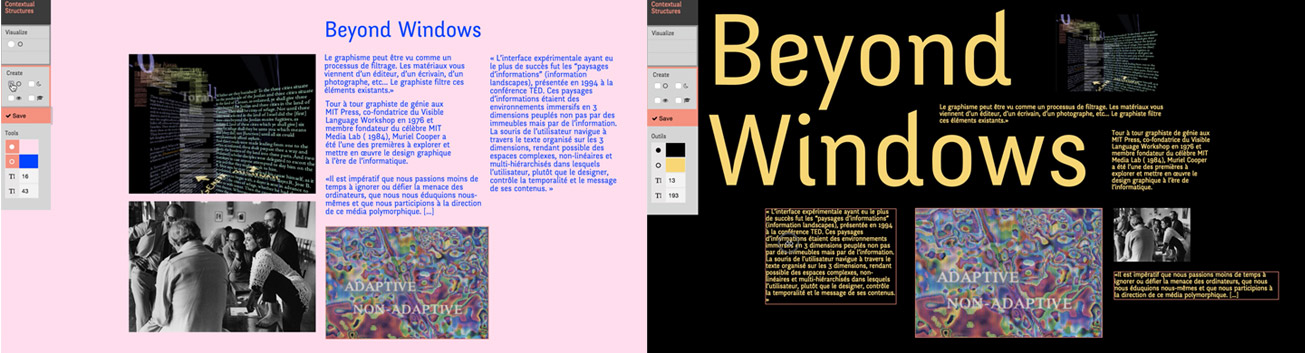

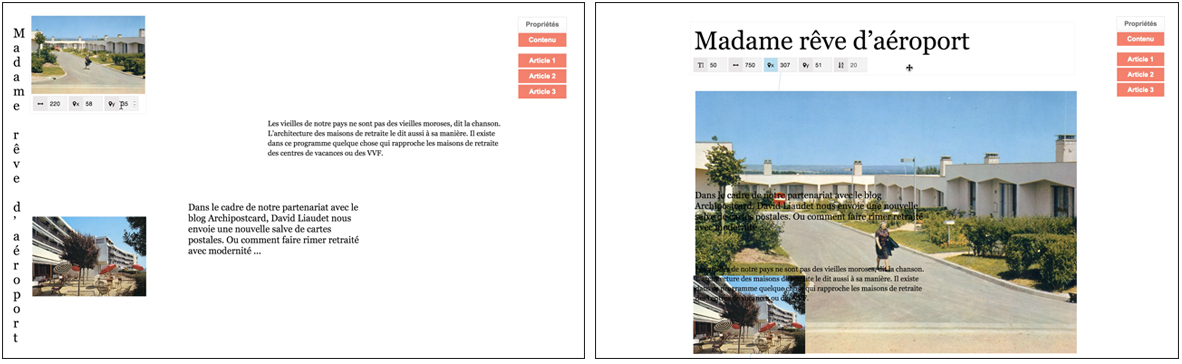

Based on my empirical findings, I propose a new type of design tools, Graphical Substrates, that combine the strengths of both programming and traditional Graphical User Interfaces.

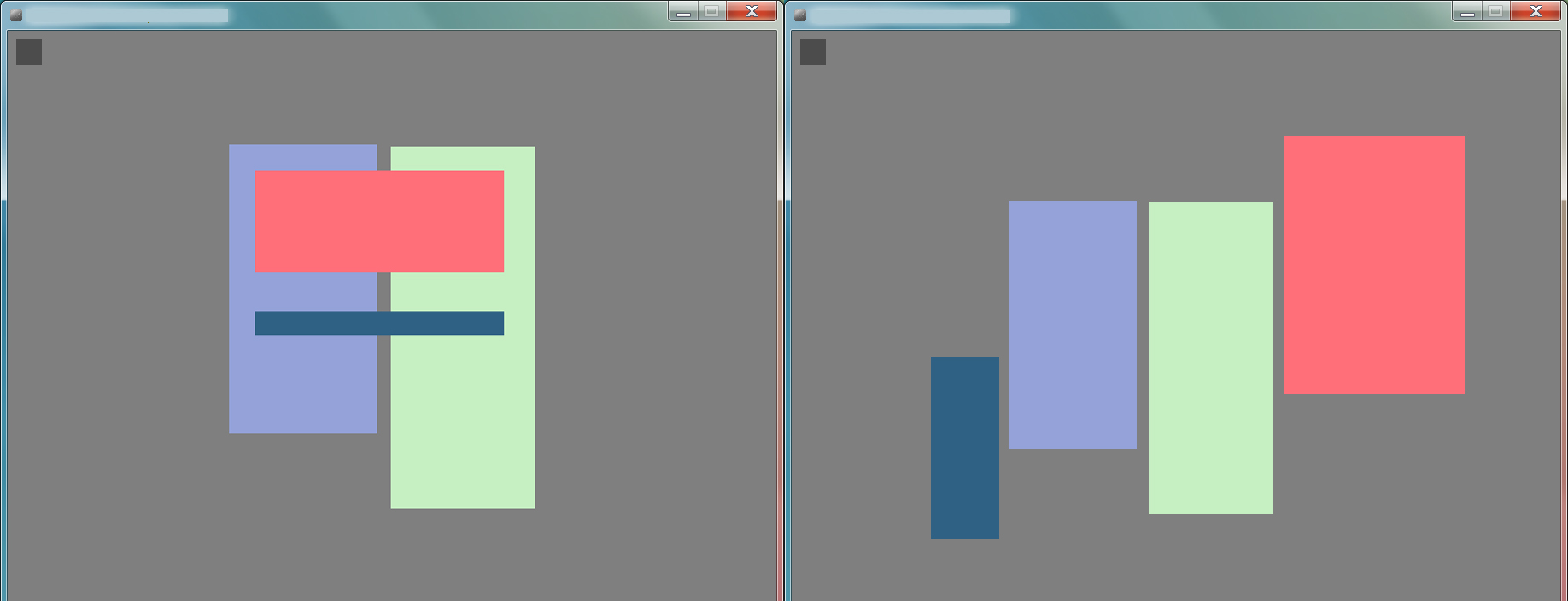

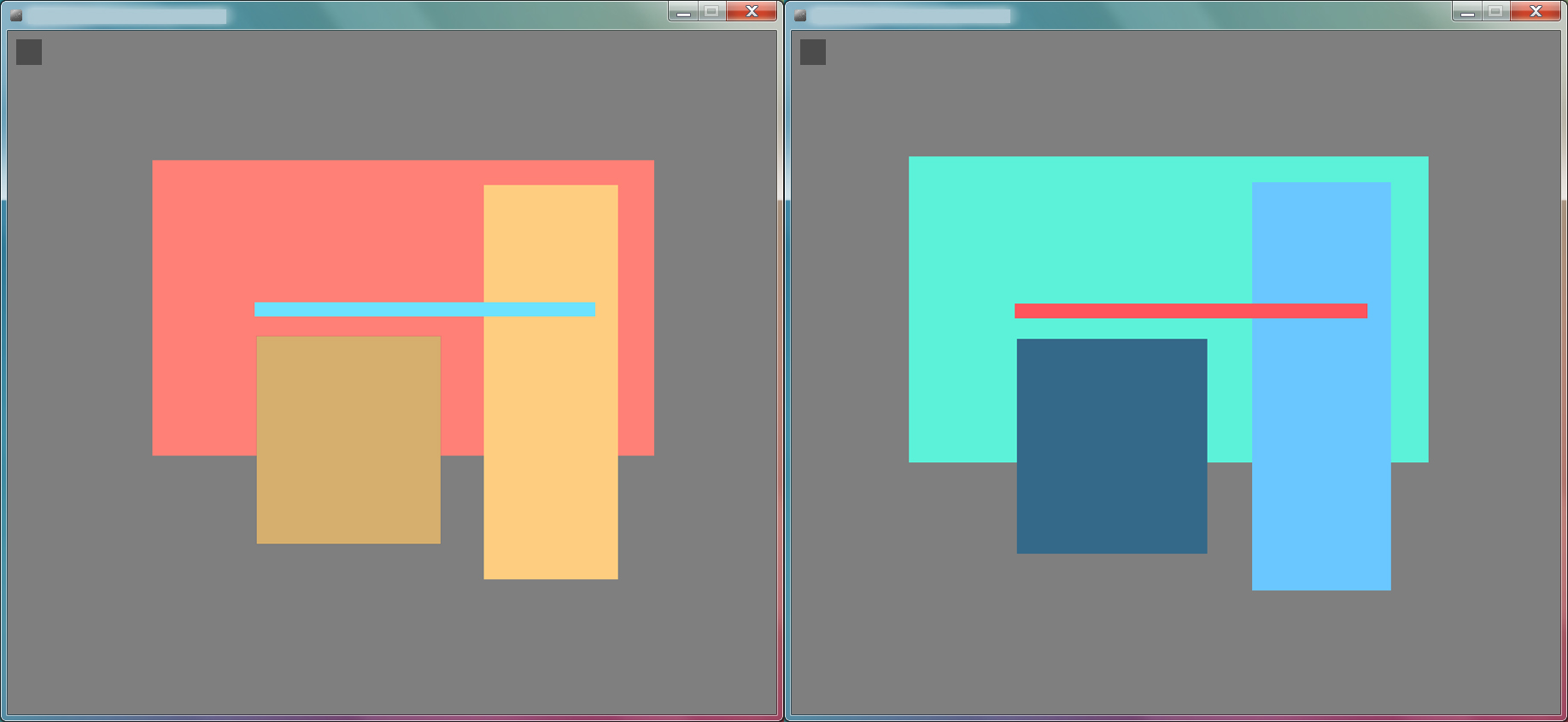

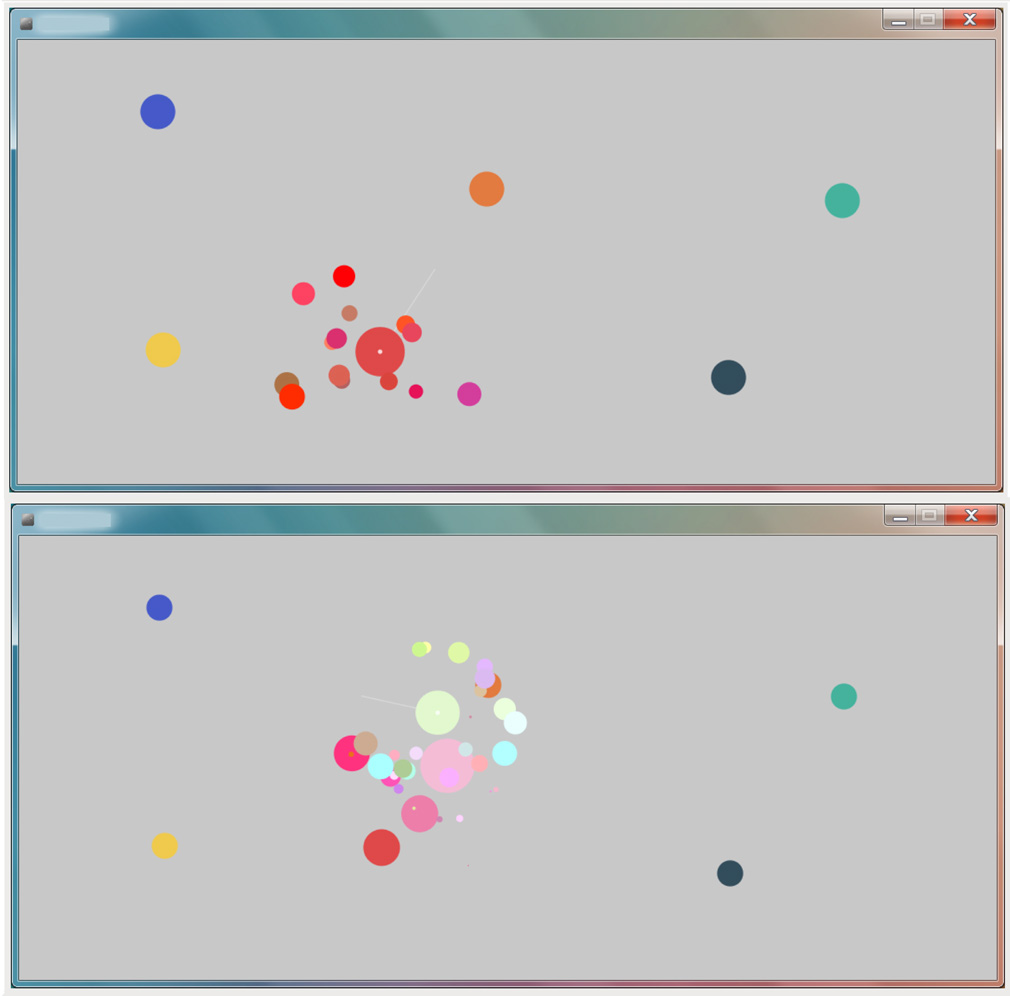

I design nine different tools that address the needs identified in the four empirical studies by reifying specific user process into Graphical Substrates probes.

In four structured observation studies, I show how designers can appropriate these probes in their own terms.

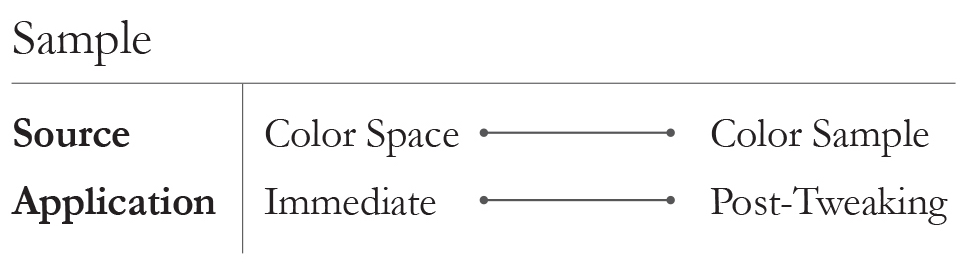

For designers to fully benefit from Graphical Substrates, I argue that they need to acknowledge the fundamental design practice of tweaking. I also argue that we should let designers reify their own graphical substrates from specific examples. I design and explore several ways to embed these two mechanisms into Graphical Substrates.

In this thesis, I argue that Graphical Substrates open the design space of designers' tools by bridging the gap between programming and graphical user interface to better support the wealth of designers' practices.

Résumé

Les outils de design graphique traditionnels n’ont que peu évolué depuis leur création, il y a plus de 25 ans. Récemment, un nombre de plus en plus important de designers commence à questionner l’invisibilité de ces outils dans le processus de design. Dans cette thèse, je m’intéresse à deux questions principales: Comment les designers travaillent-ils avec leur outils de design numériques ? Comment peut-on créer de nouveaux outils numériques pour le design qui supportent les pratiques existantes ? En utilisant StoryPortraits, une méthodologie de synthèse graphique crée pour capturer les experiences des designers en une forme qui supporte à la fois l’analyse et le design, j’étudie en premier lieu quatre pratiques de design. Celles-ci s'échelonnent depuis des opérations spécifiques telles que la sélection de couleurs, l’alignement et la distribution d’objets graphiques vers des pratiques plus complexes telles que la structuration de la mise en page et la collaboration avec des développeurs pour créer de nouvelles interactions. Dans ces quatre études empiriques, j’analyse la richesse des pratiques des designers et je caractérise le décalage existant entre les outils numériques actuels et les pratiques des designers. Je montre comment les outils du design numérique actuels détachent la créativité de l’utilisation des outils en donnant la priorité à des valeurs telles que l’efficacité et la facilité d’utilisation qui ne reflètent pas les pratiques creatives existantes. Face à ce décalage, les designers se tournent vers la programmation pour profiter d'une puissance de calcul et d’une flexibilité à laquelle ils n’ont pas accès avec leurs outils traditionnels. Je propose un nouveau type d’outil de design nommé “Substrats Graphiques”, fondé sur les résultats empiriques de mes quatre études et qui combine la souplesse et l'expressivité de la programmation avec la manipulation directe permise par les interfaces graphiques traditionnelles. Je conçois neuf outils différents qui répondent aux attentes identifiées dans mes études empiriques en réifiant (transformant en objets concrets) les processus spécifiques des designers en tant que Substrats Graphiques. À travers quatre observations structurées, je montre comment les designers s’approprient ces substrats dans leurs propres termes. Afin que les designers puissent véritablement bénéficier des Substrats Graphiques, nous devons prendre en considération la pratique fondamentale de l’ajustement. Nous devons également permettre aux designers de réifier leurs substrats à partir de leurs propres exemples. Je conçois et j’explore plusieurs manières d’intégrer ces mécanismes dans les substrats graphiques. Dans cette thèse, je soutiens que les Substrats Graphiques ouvrent l’espace des possibles des outils pour les designers en permettant de combler l’écart entre la programmation et les interfaces graphiques.

Introduction

When I first started my design curriculum, during our first class, our professors asked us to install a set of “design applications”; namely the Adobe Creative Suite. It was a prerequisite, just like having a notebook and some pencils at hand. During my studies, for each project, we were asked to carefully select the material and the industrial process we would use. We would always question the design brief and look for opportunities to challenge client assumptions about how such material was meant to be used or how such industrial or craft process had to be applied. However, not once did we consider questioning the applications that we were using at every step in the process. Design software was a dead angle in the design process.

Design software tools revolutionized the design process as soon as they were introduced in personal computers, around 1990. They greatly facilitated and optimized the different steps of the design and production process. Designers could finally access and interact with real time visualization of their work. Graphic designer and critic Ellen Lupton recalls: “being able to directly manipulate type, photography, color, and being able to see it in real time, as you are working, that’s what it’s all about, that’s the revolution” (Briar, 2017). Design software also profoundly transformed design industries themselves, especially graphic design. Behind the scene, design software led to the disappearance of many intermediary professions and thus concentrated design work in the hand of the designers themselves.

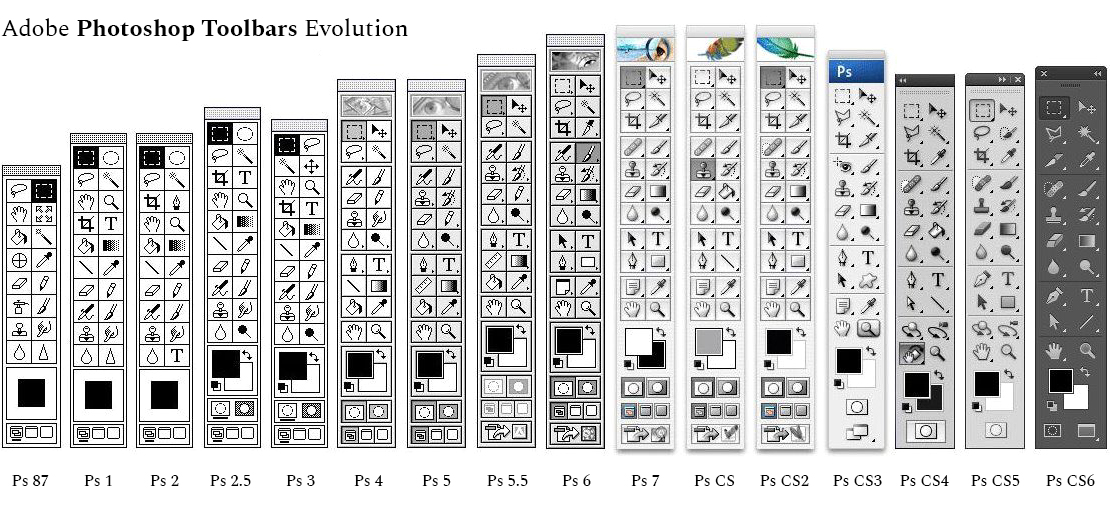

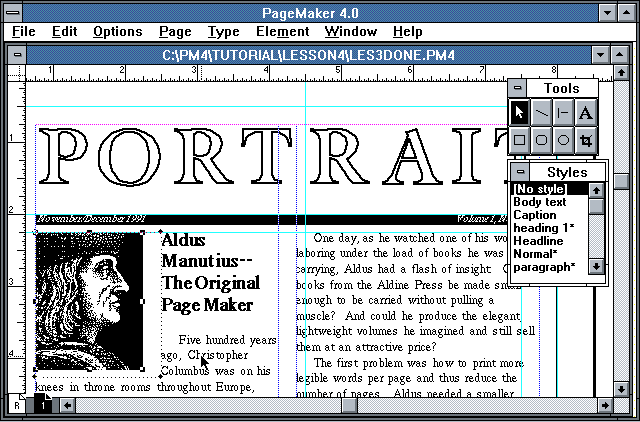

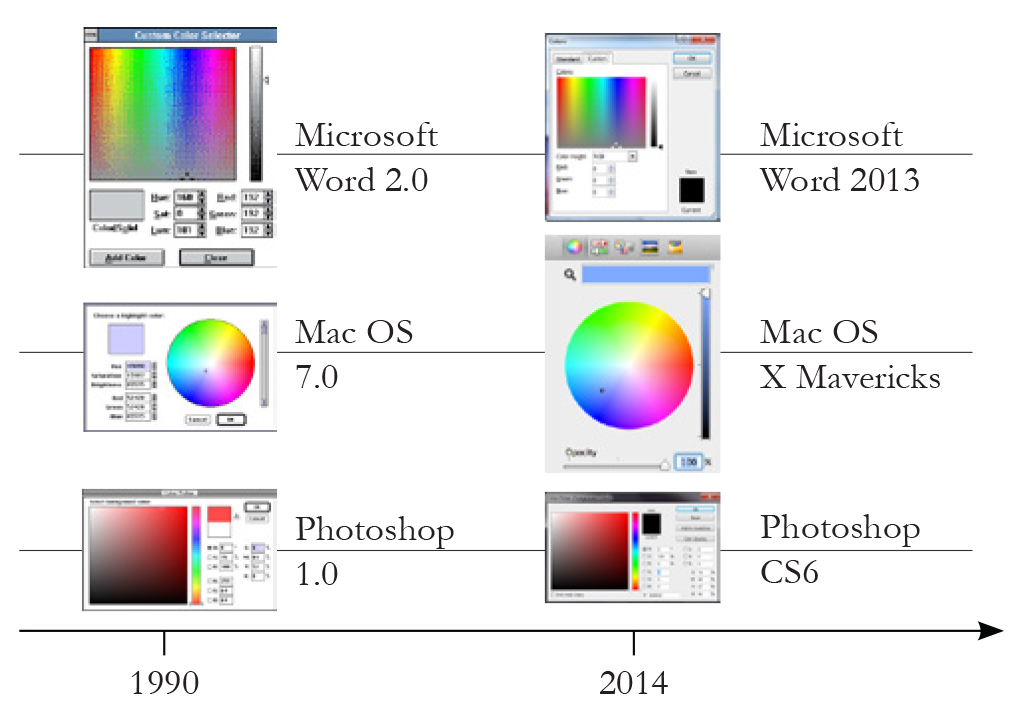

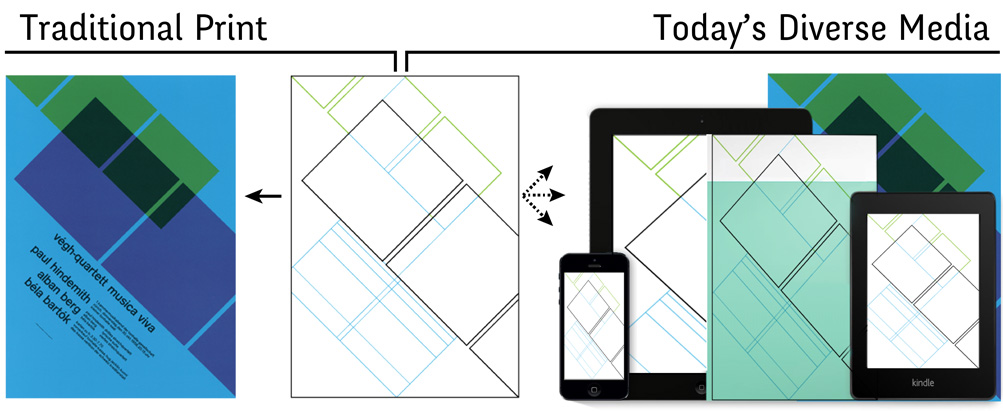

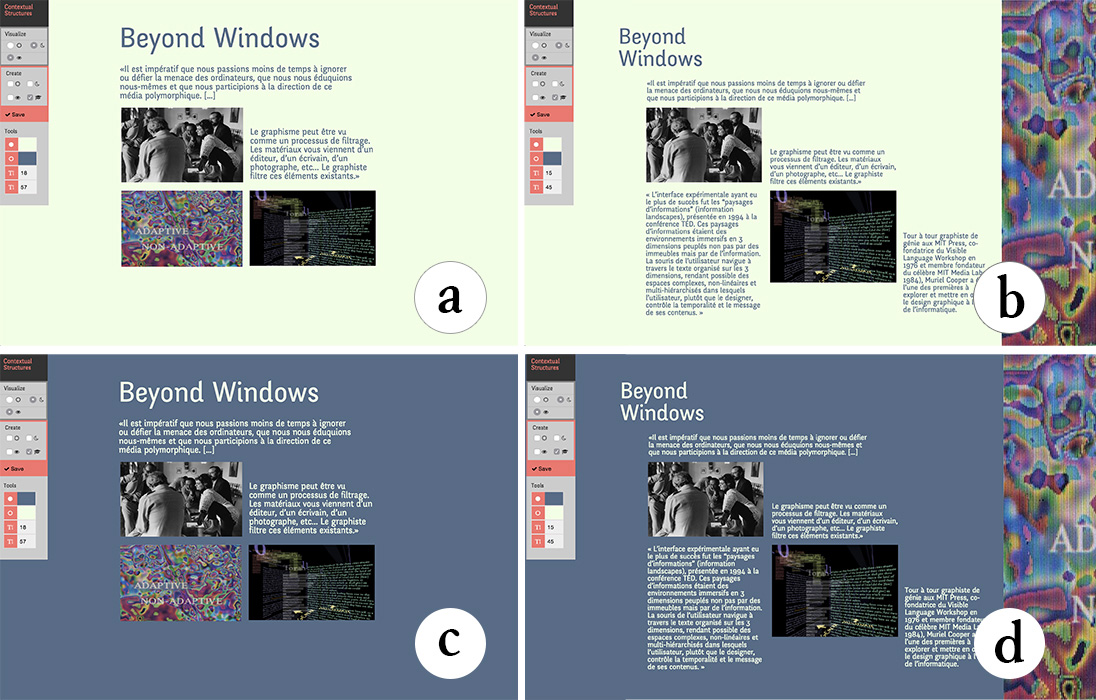

More than 25 years after, we saw the democratization of internet and the wide spread of mobile phones. Design practice accompanied this movement and many novel design disciplines appeared, including interaction design and service design. In an essay published in Digital Design Theory (Khoi, 2011), graphic designer Khoi Vinh explains that “Design solutions can no longer be concluded; they’re now works in progress, objects that continually evolve and are continually reinvented”. Yet, contrary to design practice, the digital design tools landscape mostly did not change. The same few design applications that were introduced in the 1990’s are still being used by the overwhelming majority of designers almost 30 years later. Moreover, these tools have hardly evolved. If we look at toolbars for example (), we can see that they are based on the same logic and they still provide the same tools since their origin. Rather than evolving, they “bloated” (McGrenere, 2000).

Comparison of Adobe Photoshop Toolbars since 1987. Note how little they have changed.

The stagnation of the design tool landscape led to the progressive invisibility of design software in designers practice. In fact, as New Media professor Olia Lialina demonstrated, the message from Adobe in their advertisement campaign is that the best kind of design requires designers to forget about their tools, so that they can focus on the core of their work: being creative (Lialina, 2012). The logic behind this assertion is that, ideally, the creative process should be decoupled from the tools. Thus, the invisibility of design tools should in fact become the ultimate goal for tool creators.

Does the current Design Software stagnation and invisibility imply that designers’ tools are a solved problem?

Two different elements demonstrate that design software remains an open question. First, design software invisibility is particularly striking when we consider the reasons behind design birth. Design origins are generally traced back to the industrialization of of Britain in the 19th century. For design pioneer William Morris and the British Arts and Crafts movement, the emerging industrialized mass production meant a uniformization of the resulting products, as well as a degradation in product quality (Morris, 1884). In response to this trend, they advocated for a tighter connection between design, craft and production. William Morris himself was extremely prolific and practiced dyeing, weaving, cabinet making, and printing among other crafts. Before the era of industrialization and the separation of people and the means of production, craftsmen were creating their own tools. They were extremely ingenious in adapting their tools to one’s hand size and handedness, or to achieve particular effects (). Morris sought to preserve this tradition.

While Morris and the Art and crafts movement could be considered “luddite” in their rejection of machine (Thomis, 1970), a few decades later, the pioneer Bauhaus design school encouraged its students to embrace machines and explore their potential. Designers were to appropriate industrial processes to create high quality products. (Papanek, 1972)

Few of the many trowels that can be seen at the "Maison de l’outil et de la pensée ouvrière" in Troyes, France. Note how very similar they look, yet how uniquely different each one of them is.

Thus, at the origin of design was the intention to reappropriate production means and to fusion design and production. Following this line of thought, separating the question of design and design tools is impossible. Design Software is an open issue because part of a designer’s work is to choose and question their tools. The second, and probably more important reason is an emerging reappropriation movement coming from designers themselves. In recent years, more and more designers started learning programming languages. The iconic Processing programming language and environment, launched in 2001, was among the very first tool that sought “to introduce visual designers and artists to computational design” (Reas and Fry, 2007). Its influence spread beyond graphic design and led to the Arduino project, an electronics platform aimed at facilitating the creation and prototyping of interactive products. For designers, programming offers a whole new range of dynamic capabilities that traditional software does not yet provide (Reas and McWilliams, 2010).

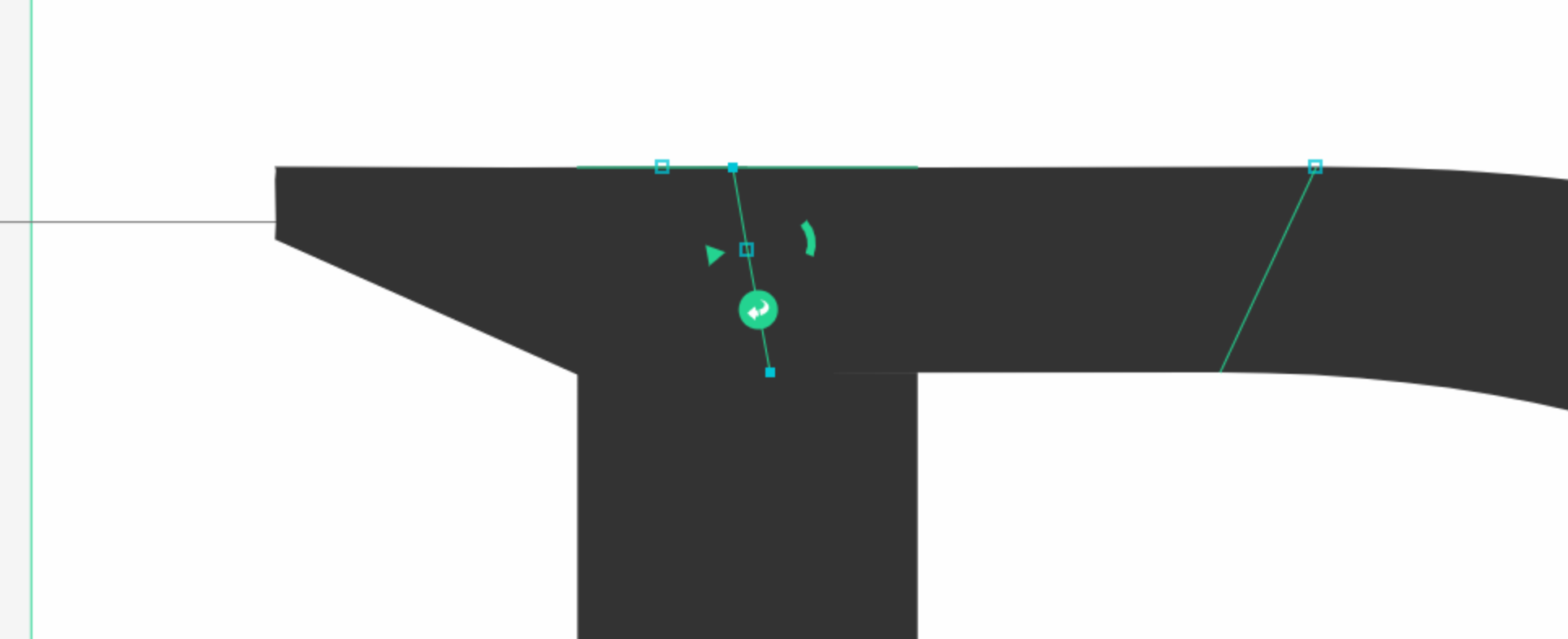

Interface detail of Prototypo, a parametric font design tool created by designer Yannick Mathey

These pioneer initiatives nurtured a new generation of designers who started building design software, usually for their own needs. In a 2012 essay commissioned by Centre National des Arts Plastiques for the magazine Graphisme en France (Reas and McWilliams, 2012), Casey Reas and Chandler McWilliams asked several designers who program their own tools: Why do you write your own software rather than only use existing software tools? How does writing your own software affect your design process and also the visual qualities of the final work? They found that some ideas were prevalent across respondents. First, designers explained that writing custom software gives them more control over the resulting artifact. The second is that new tools bring novel creative opportunities: “Experienced designers know that off-the-shelf, general software tools obscure the potential of software as a medium for expression and communication. Writing custom, unique tools with software opens new potentials for creative authorship”(Reas and McWilliams, 2012). A few designers also produce tools for other designers. An early example is Scriptographer, which lets designers extend Adobe Illustrator’s functionality by writing simple scripts in JavaScript. More recently, Prototypo is an interactive font creation software based on a parameterized customization. Prototypo is also one of the rare tools that provides a fully visual interface (). Alongside these mostly individually-led initiatives, a new design software industry is gradually emerging, with tools such as Sketch and Affinity Designer. This movement is especially visible in recent areas of design, such as interaction design. In these disciplines, the gap between the actual interaction design work and traditional software created for the printing process is especially salient.

At the same time, several designers started to question the lack of interest and diversity in design software through their writings. According to designer and design critic David Reinfurt: “Function sets, software paradigms, and user scenarios are mapped out for each software project to ensure the widest possible usability, resulting in an averaged tool which skips the highs, lows, errors, and quirks.” (Reinfurt, 2007). In his thesis “digital tools and graphic design”, graphic designer Kevin Donnot wonders “Why couldn’t we accept that tools influence us and that we could choose them depending on their impact? Shouldn’t we ask ourselves which tool is appropriate before mechanically resorting to our usual software?” (Donnot, 2011). This recent interest started bringing design software in the spotlight (Leray and Vilayphiou, 2011). Yet, if the need for novel design tools is real, we currently know very little about the current relationship between designers and their digital tools and what types of design tools would suit them.

Research Questions

Grounded in these preliminary observations about the current state of design software, I articulated two complementary sets of research questions for this thesis:

How do designers work with design software?

How do designers work with and around design tools? How do they appropriate existing software and adapt it for their specific practices? How do current design tools support these practices.

How can we create design tools that better support design practice?

What tools can we create to support current design practices? How would designers work with these new tools, and how would these tools influence their existing practices?

The reflective aspect of these first two questions call for a second set of broader questions on the nature of design tools. Designers design for others. But how should we design for designers? How does designing tools for designers differ from designing other tools? Can we use the same principles to design for creativity and for productivity?

Definitions

Design is a very broad and multi-disciplinary field, involving many different practices, cultures and traditions. In my thesis, I chose to focus on graphic design and interaction design. Graphic designers professionally create documents, laying out content in space. Yet, many aspects of their work, including choosing color, aligning visual elements or even creating layouts are not exclusively the prerogative of graphic designers. Many different professions create documents as part of their daily work. Even if they don’t focus on the graphic design aspect of these documents, they nevertheless need to carry the same design tasks. New tools created for designers could potentially also transform how these non-professional perform their own design tasks. Even within this limited scope, graphic design practices are extremely diverse. To study design tools from complementary angles, I focus on successive task levels, starting from very focused and specific tasks to more and more higher level, structural and collaborative, tasks. I started with extremely focused practices: color selection as well as alignment and distribution, which are intrinsic to most design work. Yet, these two tasks are only one specific aspect of any design project. To complement these first two inquiries, I then turned to a more complex design task, layout structuring. Unlike color and alignment, current design software applications do not include a single dedicated tool for layout manipulation. Finally, I studied designer-developer collaboration when creating interactive systems. These four different design activities, address design tools from different perspectives and scales.

Defining design tools might be an endless endeavor, because the intricate architecture of software tends to blend different levels of granularity. In this thesis, I define design tools as individual tools within design applications such as Adobe Illustrator and InDesign. For example, in this thesis, I call design tools individual panels and commands such as color pickers, alignment commands, levels panel, Adobe Photoshop filters, etc. I otherwise use the term design software application to refer to design applications such as Adobe Illustrator, Photoshop and InDesign that include a wide variety of design tools.

Research Approach

This thesis is at the cross-roads of design and human-computer interaction. Over the course of this PhD, I positioned myself as a design researcher borrowing from HCI methodologies. Design research is a relatively new field of research, and, not unlike Human-Computer Interaction, is still arguing over a canonical definition. But before trying to define design research, I must first settle on a definition of design. Many have been proposed, but for the sake of convenience and because it fits my personal philosophy rather well, I chose the definition proposed by Herbert Simon in 1969:

“everyone designs who devises courses of action aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones.”

―Herbert Simon in The Sciences of the Artificial, p.130

One could argue that this goal is shared with engineering. A key differences, however, is that design focuses on what Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber in 1973 called "Wicked Problems" (Rittel and Webber, 1973). Wicked Problems cannot be easily addressed through science and engineering methods. Rittel and Webber coined this term “in reaction to the casting of design as a science and also in response to systems engineers’ inability to apply scientific methods to address social problems”. Zimmerman explains that wicked problems cannot be accurately modeled, because the different stakeholders hold conflicting perspectives of the issue at hand. It is therefore impossible to adress this problem using “the reductionist approaches of science and engineering” (Zimmerman et al., 2007).

Now that we have proposed a definition of design, we can approach a definition of design research. Frayling, Professor at the Royal College of Art, proposed a classification of design research in three components (Frayling, 1993): Research for design, Research into design and Research through design. Findeli, in 2004, redefined these three types of design research (Findeli, 2004) as follows:

“Research for design” aims at guiding design practice. This research is collected by designers to document different aspects of their project (technical, sociological, ergonomics...) that will then be used to nourish their design process.

“Research into design” is mainly found in universities and research centres contributing to a scientific discipline studying design. It documents objects, phenomena and history of design.

“Research through design” is the closest to the actual design practice. Designer/researchers who use Research through Design seek knowledge and understanding through the making of artefacts.

My thesis follows a “Research through design” approach. More concretely, Findeli’s description again as his description of research through design practice accurately reflects my own practice:

“the aim of designers is to modify human-environment interactions and to transform them into preferred ones. Their stance is prescriptive and diagnostic. Indeed, design researchers, being also trained as designers – a fundamental prerequisite – are endowed with the intellectual culture of design; they not only look at what is going on in the world (descriptive stance), they look for what is going wrong in the world (diagnostic stance) in order, hopefully, to improve the situation. [...] Their epistemological stance may thus be characterized as projective.” (Findeli, 2004)

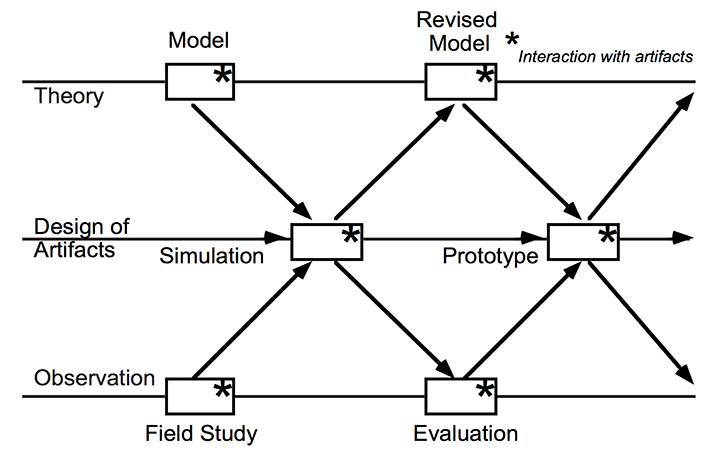

-Mackay and Fayard’s triangulation framework, articulated around theory, design of artifacts and observation.

According to Pedgley (Pedgley, 2007), one of the main obstacles to acquiring knowledge with this method is that “Designers are not used to accounting for what they know or do”. Schön also concur that this type of knowledge is “implicit to our patterns of action and in our feel for the stuff with which we are dealing” (Schön, 1984). To address this issue, I conducted my PhD using Mackay and Fayard’s triangulation framework, originally defined in the context of Human-Computer Interaction (). As Mackay and Fayard pointed out, “HCI cannot be considered a pure natural science because it studies the interaction between people and artificially-created artifacts, rather than naturally-occurring phenomena, which violates several basic assumptions of natural science” (Mackay and Fayard, 1997) In order to integrate design and scientific knowledge, they propose to iterate over three different levels: theory, artifact design and observation. Findings from each of these steps nurture the subsequents. Following this framework, I articulated my thesis contributions around this threefold structure.

Following design researcher Bill Gaver’s demand for new artifacts to manifest and exhibit design research results (Gaver and Bowers, 2012), I produced artifacts to explicit my findings at each level in the process. These artifacts are the foundation of the present thesis.

Thesis Statement

My thesis concerns the mismatch between the principles underlying current graphic design tools and the daily practices of graphic designers. Mainstream design tools decouple creativity from tool use and prioritize values such as efficiency and user-friendliness that do not reflect designers’ needs. I propose to turn graphical design substrates, the ad hoc principles created and used by designers in their work, into design tools that bridge the gap between graphical design tools and programming. Graphical Substrates can be turned into interactive objects that represent and mediate relationships among graphical elements. These reified relationships can scaffold and evolve during designers’ exploration phase. I demonstrate how we can create Graphical Substrates directly from specific designers’ practices and how we can let designers themselves reify their own graphical substrates from their unique examples. By integrating tweaking mechanisms in the substrates themselves, they can become a novel type of flexible and powerful design tools.

Thesis Overview

In Chapter 2, I analyze the differences among design software application that were developed by computer scientists, by the industry and by designers themselves. I also review the impact of design software from three perspectives: designer's accounts, empirical studies and media studies analyses.

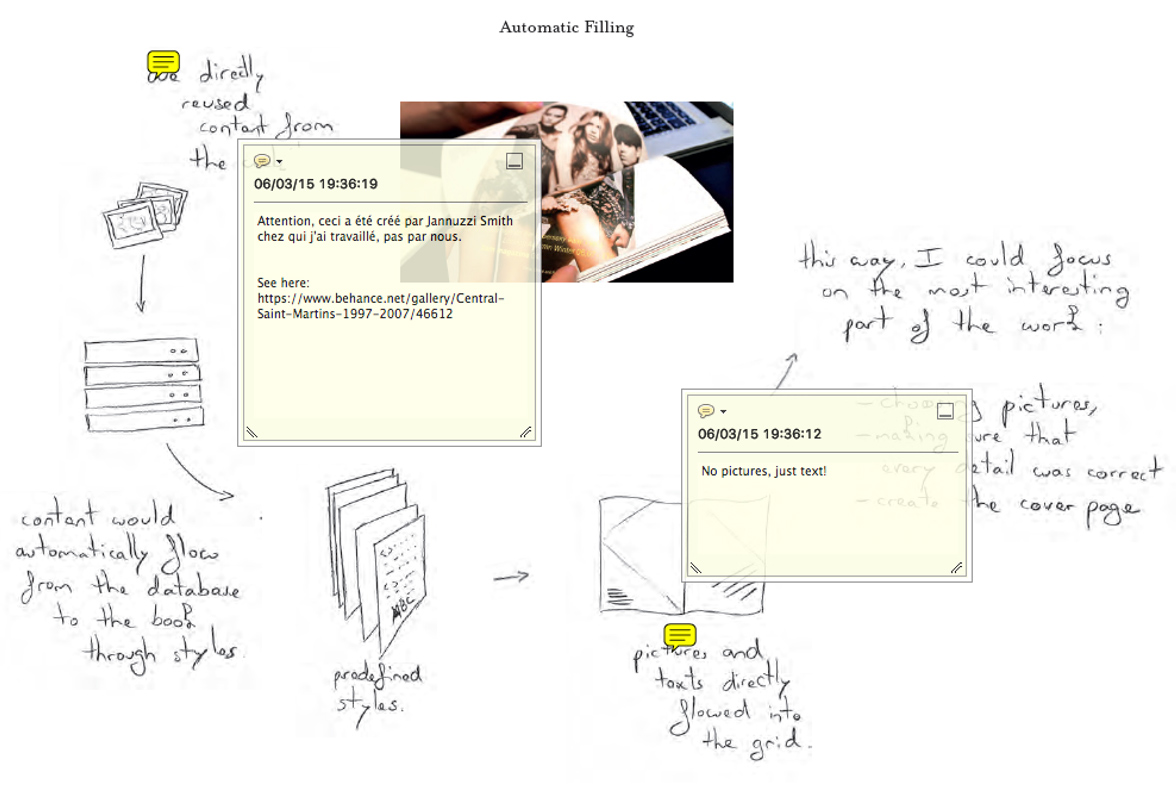

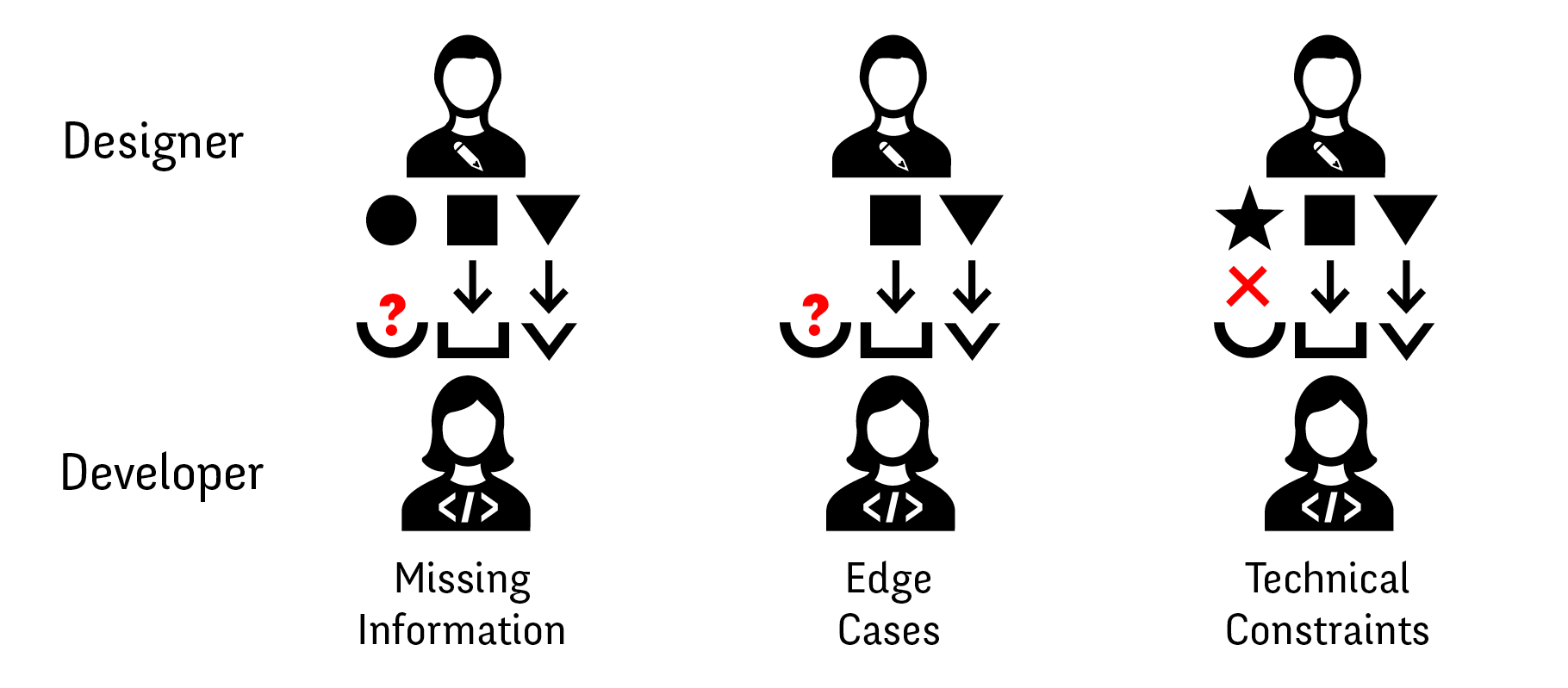

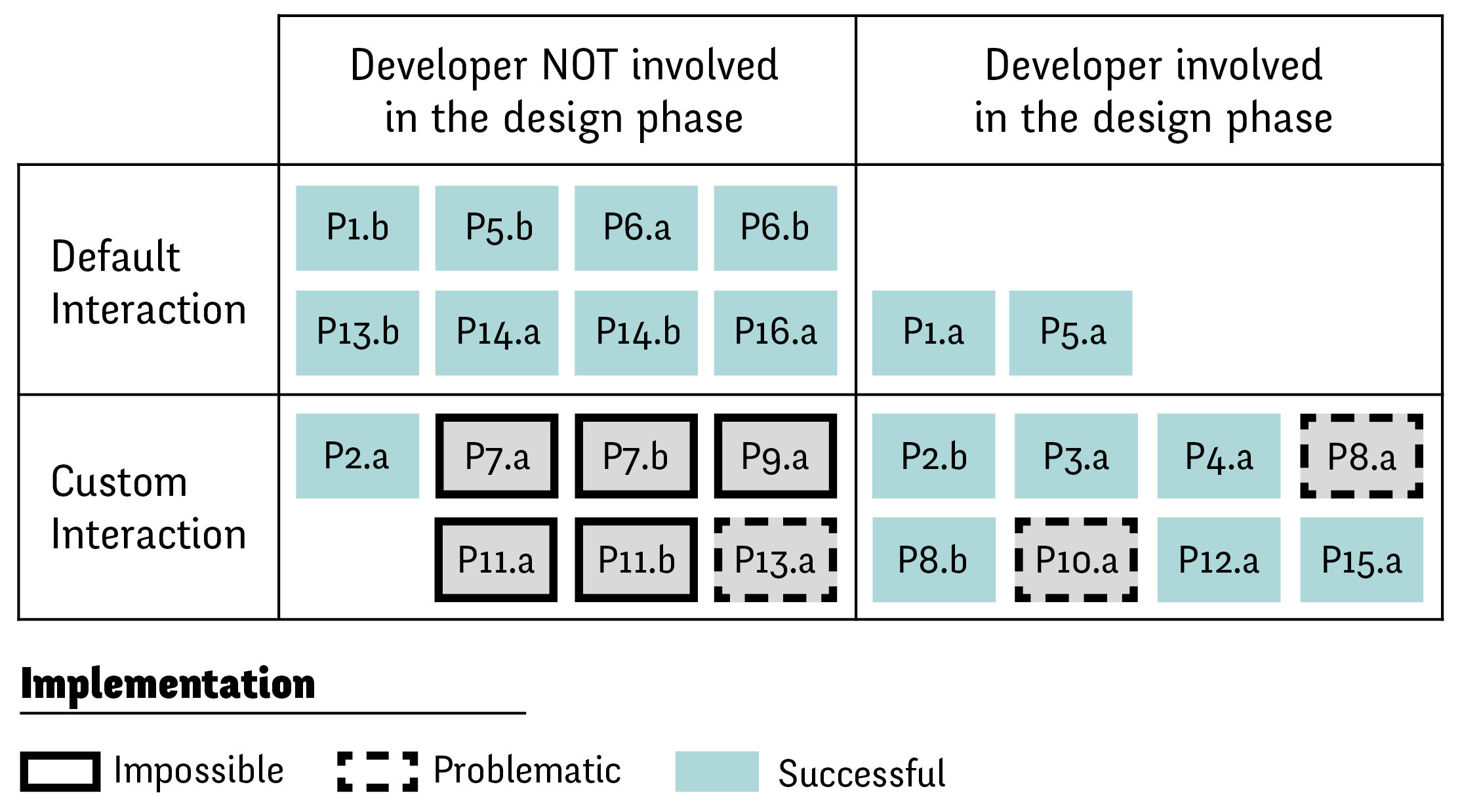

I then divide my thesis in two parts, each targeting one of the two sets of research questions presented above. In the first part of the thesis, I investigate designers' practices with digital tools by studying four complementary practices. In chapter 3, I present StoryPortraits, a technique for interviewing, synthesizing and visualizing designers’ stories into a form that supports later analysis, and inspires design ideas. In chapter 4, I inquire into designers practices with color. I present the Color Portraits Design Space that characterize five key color manipulation activities that demonstrate the breadth of designers interaction with color. I validate the Color Portraits Design Space with scientists and engineers before using it to analyze the limitations of current color tools. In chapter 5, I study alignment and distribution practices with professional designers and regular users of authoring software. I analyze the main limits of the current alignment and distribution commands. In chapter 6, I present a study of designers strategies to structure layout. We explore the wealth of strategies and present the “graphical substrates” framework: underlying structures onto which designers organize their layout. I analyze how designers who code can reify their substrates and develop them further. In chapter 7, I present two studies exploring the collaboration issues and strategies between designers and developers. I show how their current tools require a lot of reworking and redundancies that introduce mismatches. We call these mismatches design breakdowns and divide them in three categories: missing information, edge cases and technical constraints. In chapter 8, I discuss the results of the four previous chapters to understand commonalities among design tools. I analyze the mismatch between designers' practices and the underlying principles behind design tools.

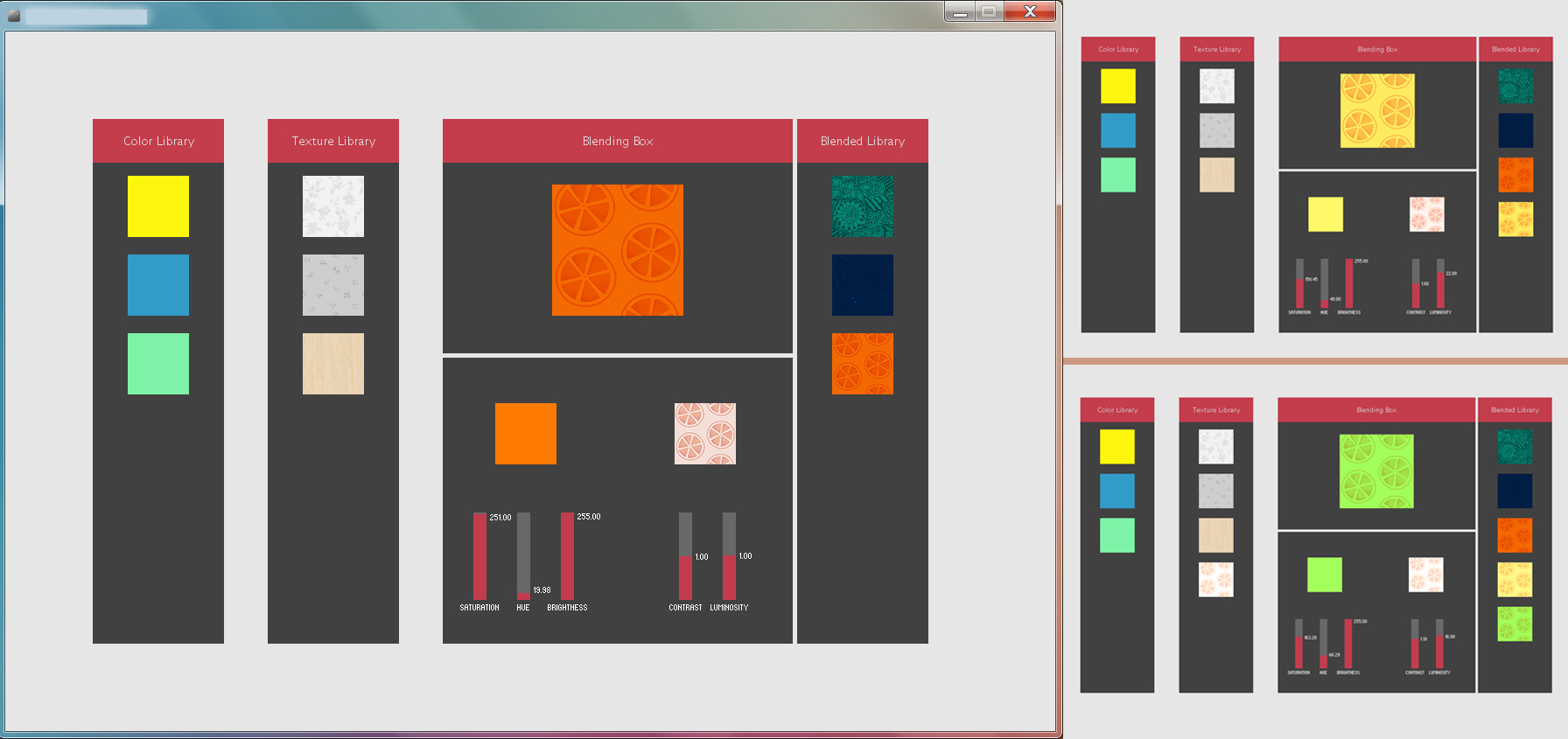

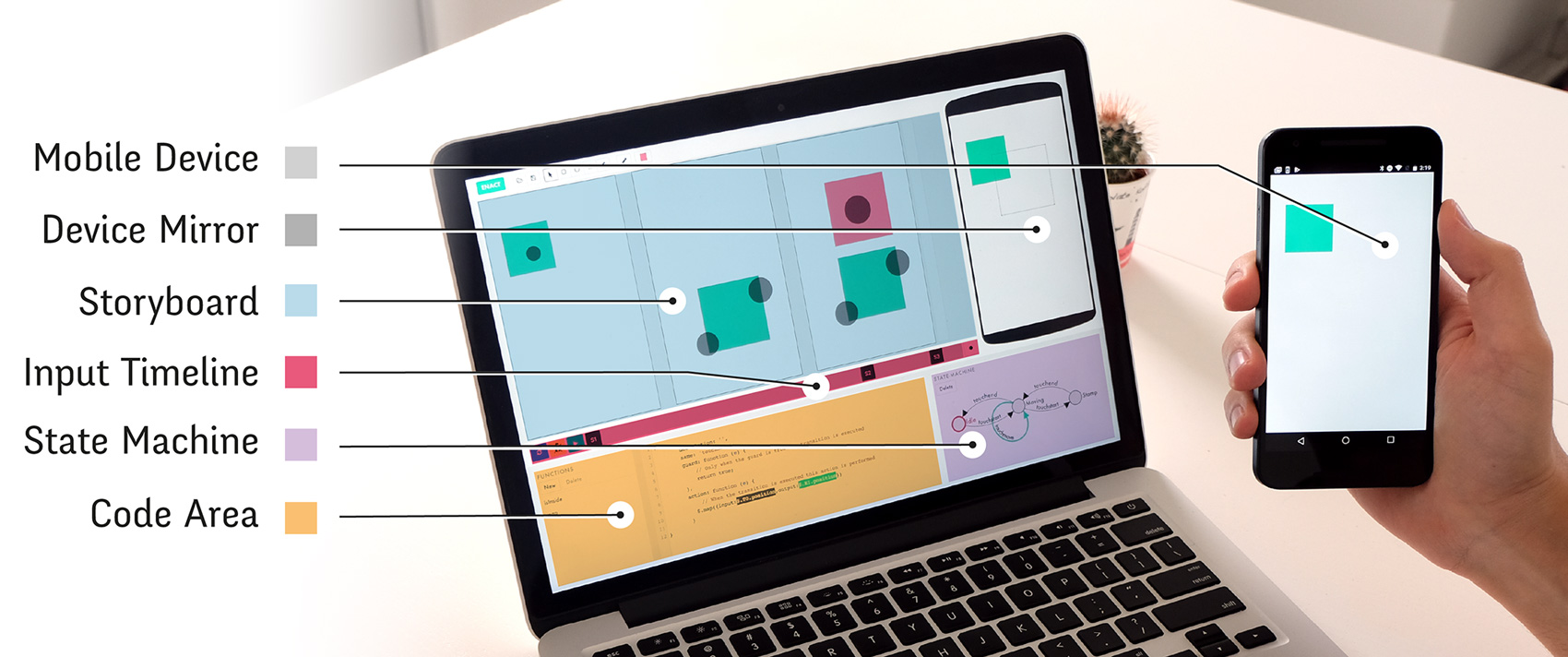

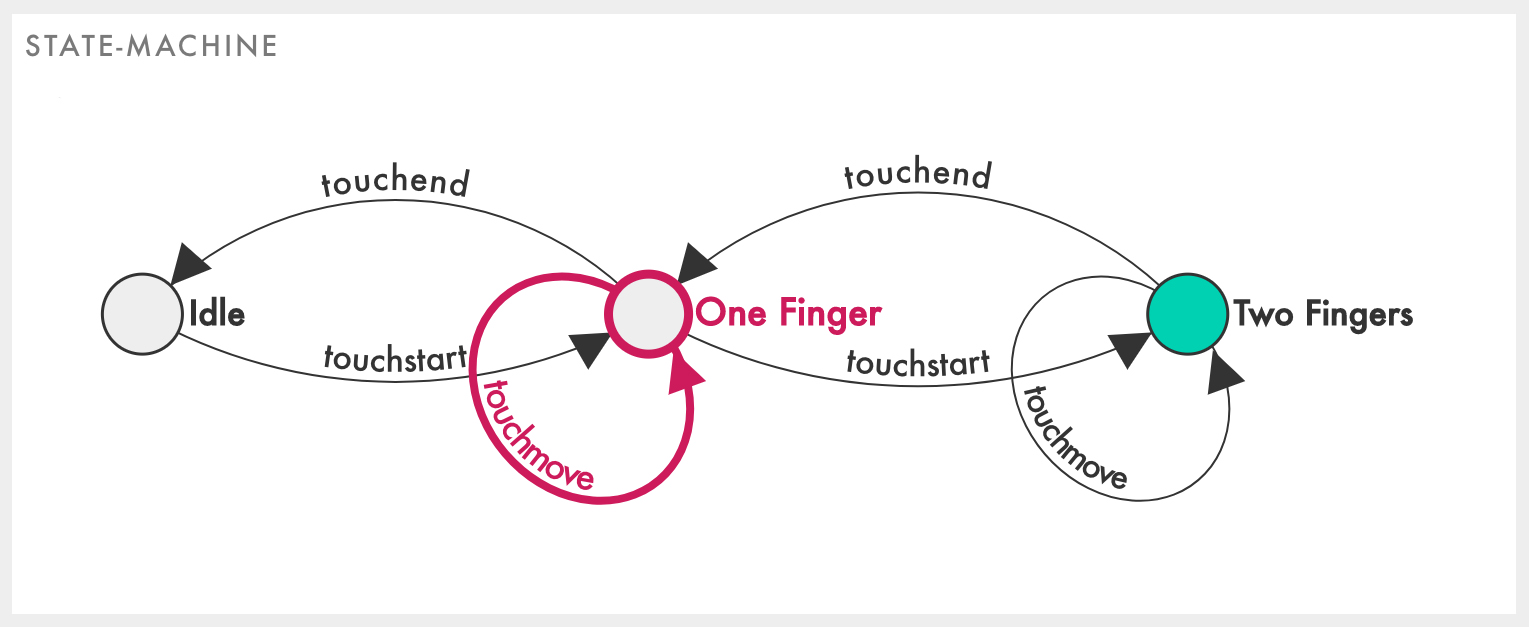

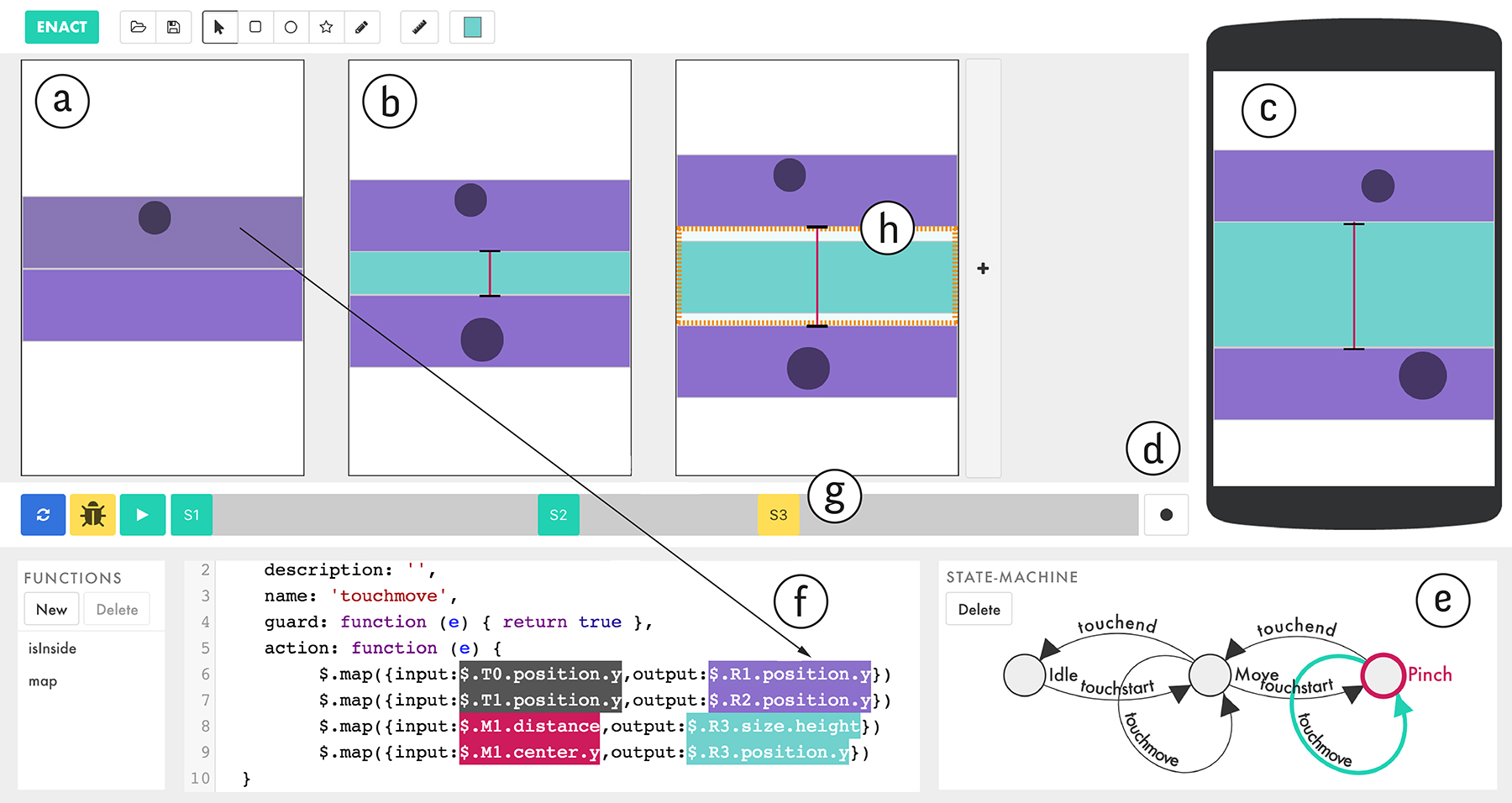

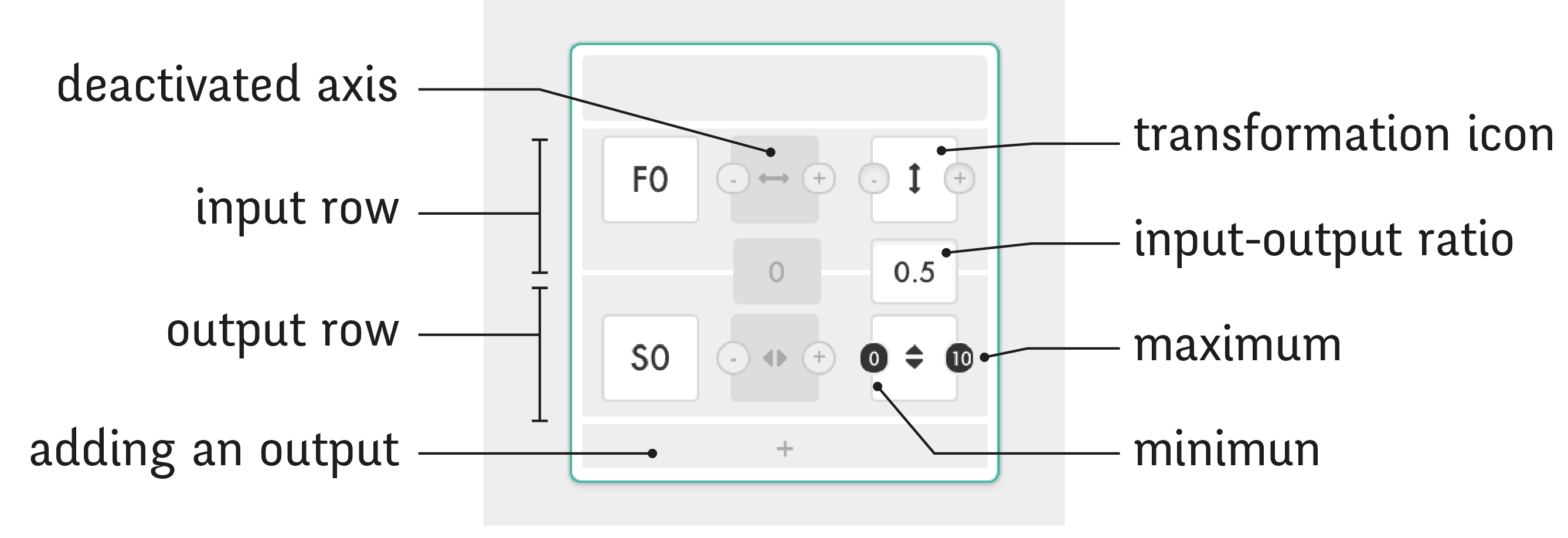

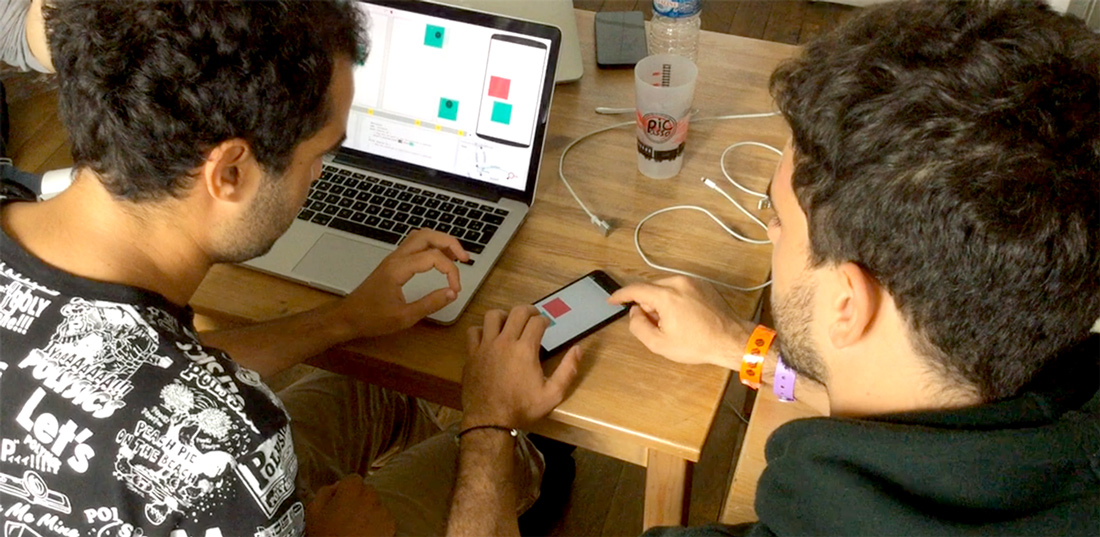

In the second part of the thesis, I investigate how we can create and explore design tools that support the activities described in the first part. In chapter 9, I present four color tools supporting the corresponding practices identified in the ColorPortraits Design Space. I explore them as probes (Hutchinson & al., 2003), as new means of understanding how designers work, with designers and scientists to understand how they can interpret them in their own work. In chapter 11, I explore how we can reify graphical substrates through two first probes directly inspired by designer' stories. I explore these probes with graphic designers and I incorporate their feedback in a prototype that fully reifies graphical substrates in the context of CSS. In chapter 12, I present Enact, a tool that facilitates the transition phase between designers and developers during the creation of interaction. We first start with a participatory design workshop to elicit novel ways of representing the interaction that satisfies both professions. We build Enact based on this feedback, combining interconnected visual, symbolic and interactive views. I then explore how it affects designers and developers collaboration through structured observation studies. In chapter 13, I discuss the different tools and propose principles for the creation of design tools that better reflect and support existing designers' practices.

Background

In this chapter I propose a brief analysis of the history of graphic design software applications to better situate and understand the current relationship between designers and their digital tools. In this chapter, I discuss graphic design tools mostly at the software application level. In each subsequent chapter of this thesis, I provide a more detailed related work to situate each project in its specific context.

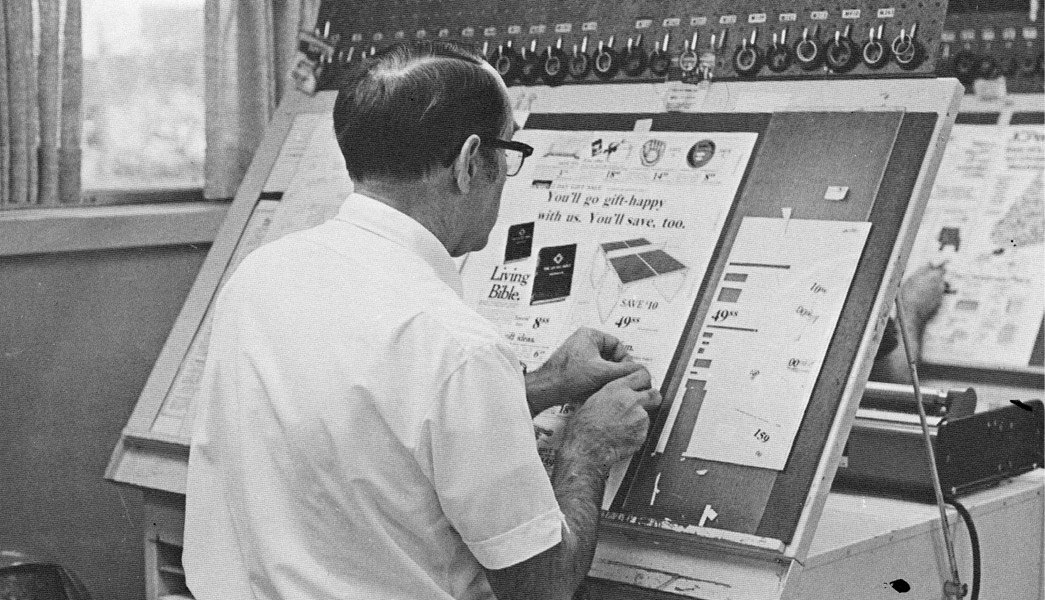

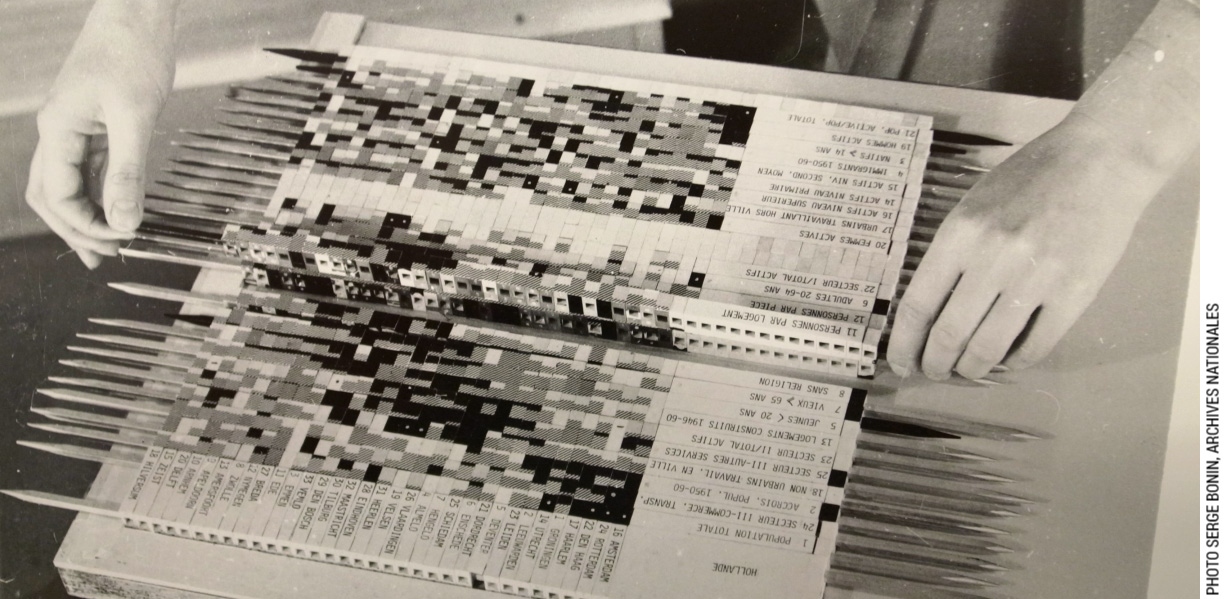

I divide this chapter in two complementary sections: I first analyze the history of graphic design software from the perspective of their creators. I explore how design software gradually came to be, what were the the underlying conceptions behind them and how did they differ from pre-existing techniques (). To do so, I identify and explain how design software applications were produced and envisioned from three complementary perspectives: from computer science research, from the industry and from designers themselves. In the second part of this chapter, I inquire into what we know of the relationship between designers and graphic design software applications. I explore how designers perceive these digital design tools and how they work with them. I also report on three different perspectives that provide complementary insights: designers writings on the early moments of digital design software, empirical studies of the impact of the computer on designers' practice as well as a few theories developed, both in HCI and in Media studies, to understand the impact and the logic of digital design tools.

Design Software -

creator perspectives

In the first part of the background, I present a succinct history of digital graphical design software applications. If we want to study how designers work with their tools, we first need to understand how did these tools come to be. Obviously, the history of tools for design is a very complex and intricate one. My goal here is not to provide a precise and exhaustive history -for a first hand account on the history of paint software, for example, see Smith's (Smith, 2001)- it is instead to understand how producing design tools can be done very differently in different contexts. According to Suchman (Suchman, 2007), “Every human tool relies on, and materializes, some underlying conception of the activity that it is designed to support”. Designers design for others. But who designs for designers? Studying the intention behind software can help us understand the hidden assumptions that often go unquestioned. According to philosopher of technology Simondon (Simondon, 1958), a study of technology should not approach technology from an individual perspective. Instead, each technical object belongs to a technical lineage and cannot be fully understood outside of it.

Prior to using design software applications, designers used to create layouts through “paste-up”, cutting and pasting different content elements onto a blank page.

In this section, I present three main lineages of graphic design software applications. These three lineages and their resulting software applications obviously influenced each other. This is especially true from the research world to the industry (Myers, 1998), but they nevertheless were designed in very different contexts and for very different purposes. The first type of design software applications emerged as experiments by computer scientists. They used design software as a way to explore and enhance the potential of computers. The second wave of graphic design software applications came later from the industry and sought to replace traditional graphic design tools. Therefore, creators tailored design software applications for integrating them into pre-existing workflows and facilitating designers adoption. The third lineage are design tools created by graphic designers themselves. Because designers were working for themselves, they could explore how graphic design software impacted their work and generally tried to reinvent what graphic design meant.

Design Software

from a Research perspective

The first computers, built before and during World War II, were designed and used as powerful calculators “for specific purposes, such as solving equations or breaking codes” (Grudin, 2012). Therefore, the first computer users were mathematicians. When a single computer would fill an entire room and required programs to be written on punched cards, it could be hard to imagine the versatility that we are accustomed to today. The gradual shift towards designing computers as tools for creation first happened in the research world, as computer scientists started questioning the relationship between people and computers. The following projects were never commercialized and thus never used by professional designers, yet they all were pioneers in recognizing the power of the computer as a design tool.

Memex (1945) and Xanadu (1960)

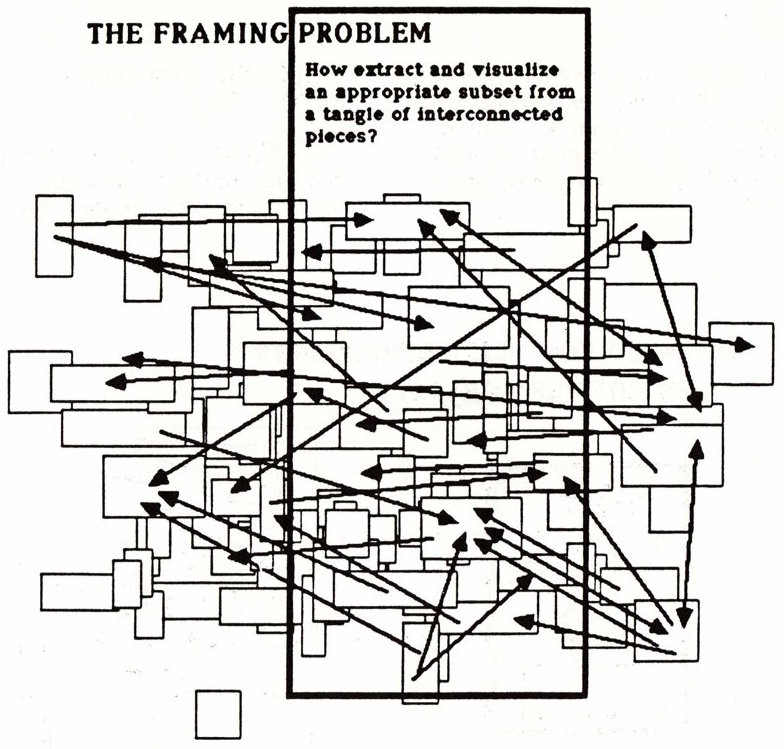

-The Framing Problem, “How [to] extract and visualize an appropriate subset from a tangle of interconnected pieces”, by Ted Nelson in Computer Lib/Dream Machines, 1974

The Memex was not a tool for designers per se, but it pioneered a vision of computers that would deeply affect how we access information, ultimately questioning the role of design. In 1945, at the end of the war, Vanevar Bush, in his visionary article “As we may think” (Bush, 1945), proposed to shift the vision of computing to envision the computer as an empowering tool available to everyone. According to Bush, a Memex would become the equivalent of a private library, it would help individuals store all their books, records and communications, “an enlarged intimate supplement to his memory”. Even if it was never built, the Memex had a great influence on the subsequent development of tools to shape information and on human-computer interaction as a whole. As design researcher Masure explains, the infinite storage envisioned by Bush questions the modalities of access of this content (Masure, 2014). How should the content be presented? In that sense, the Memex was already a tool for design, carrying the seeds of the future that designers need to shape today. Deeply inspired by Vanevar Bush’s vision, Ted Nelson, developed the notions of hypertext, and hypermedia: interconnected text, graphics and sounds.

His book Computer Lib/Dream Machines, published in 1974, is a peculiar graphical object in itself (Nelson, 1974), following the precepts of hypertext. With his project Xanadu, initiated in 1960, Nelson questions the practice of graphic design by proposing a hypertext system that defies the idea of fixed content. In his book, he envisioned some of the impact that hypertext would have on designers. For example, he envisioned “the Framing Problem: How (to) extract and visualize an appropriate subset from a tangle of interconnected pieces” (). HyperText influenced the World Wide Web creator Tim Berners Lee and provided the foundations for the new world graphic designers currently need to shape.

Sketchpad (1963)

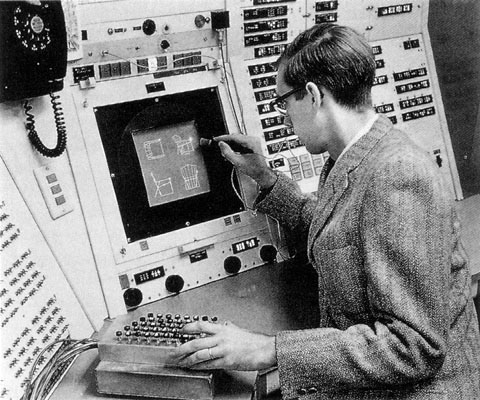

-Sutherland’s Sketchpad system. Built in 1963, it is considered to be the first visual interface and, coincidentally, the first digital design tool

In 1963, Ivan Sutherland published his PhD dissertation in which he presented the groundbreaking Sketchpad system. Usually considered the first graphically based interactive system, it was developed at the MIT’s Lincoln Lab under the direction of Claude Shannon, father of information theory. This application demonstrates a few groundbreaking principles, some of which are yet to be seen in common Computer Aided Design applications or graphic design software today. Using a light pen as a pointer directly onto the screen, Sketchpad lets designers create shapes on the screen by creating points onto the screen (). Using command keys on a separate keyboard, designers can create and apply constraints, such as making two lines perpendicular or parallel. Sutherland also introduces an object oriented approach (before it even existed in programming languages). Instead of having to manually create multiple copies of a same shape, Sketchpad lets designers create and instantiate objects. Changes made to the original shape are reflected in all its instances. Among other features, Sketchpad also provides a zooming interface. The initial goal, according to Sutherland, was to make the computer “more approachable” ( Sutherland, 1963) by using displays. Sutherland wanted to explore drawing as a new way to interact with the computer. His thesis title, “a man-machine graphical communication system”, makes explicit this vision, one of a partnership between humans and machines.

Sketchpad was not design to support existing practices nor replace traditional tools in the industry. According to Sutherland himself, the principles behind Sketchpad are inspired by his interaction with the computer as well as by programming concepts (constraints and object oriented programming).

It has turned out that the properties of a computer drawing are entirely different from a paper drawing not only because of the accuracy, ease of drawing, and speed of erasing provided by the computer, but also primarily because the ability to move drawing parts around on a computer drawing without the need to erase them. Had a working system not been developed, our thinking would have been too strongly influenced by a lifetime of drawing on paper to discover many of the useful services that the computer can provide (Sutherland, 1963)

Sketchpad paved the way for CAD (Computer Aided Design) software as well as for HCI (Human-Computer Interaction) as a whole. Among others, it notably inspired Douglas Engelbart (Engelbart, 1962).

Genesys (1969)

Genesys is another interesting early example of a design software: “An Interactive Computer-Mediated Animation System”. It was built for creating animation by Ron Baecker in 1969, as part of his PhD at the MIT’s Lincoln Lab. The system uses a Rand Tablet, ancestor of today’s graphic tablets. One of the key notions of GENESYS is that animations are “movements-that-are-drawn”. A hand-drawn picture can either be a visible object to be animated, or a motion path for other graphical objects. Furthermore, not only could an object follow a hand-drawn motion path, it could do so with the same velocity and dynamism that was used to draw the line ().

-Ron Baecker’s Genesys. Built in 1969, it is the first digital tool explicitly designed to support animators’ practices.

Contrary to Sketchpad, and visionary at its time, GENESYS was directly inspired by animators’ way of working. Baecker even tested his system with professionals and asked them for feedback. Baecker also stresses that “The computer is an artistic and animation medium, a powerful aid in the creation of beautiful visual phenomena, and not merely a tool for the drafting of regular or repetitive pictures” (Baecker, 1969). This new vision of the computer, as a creativity support tool remained peculiar for a long time.

Pygmalion (1975)

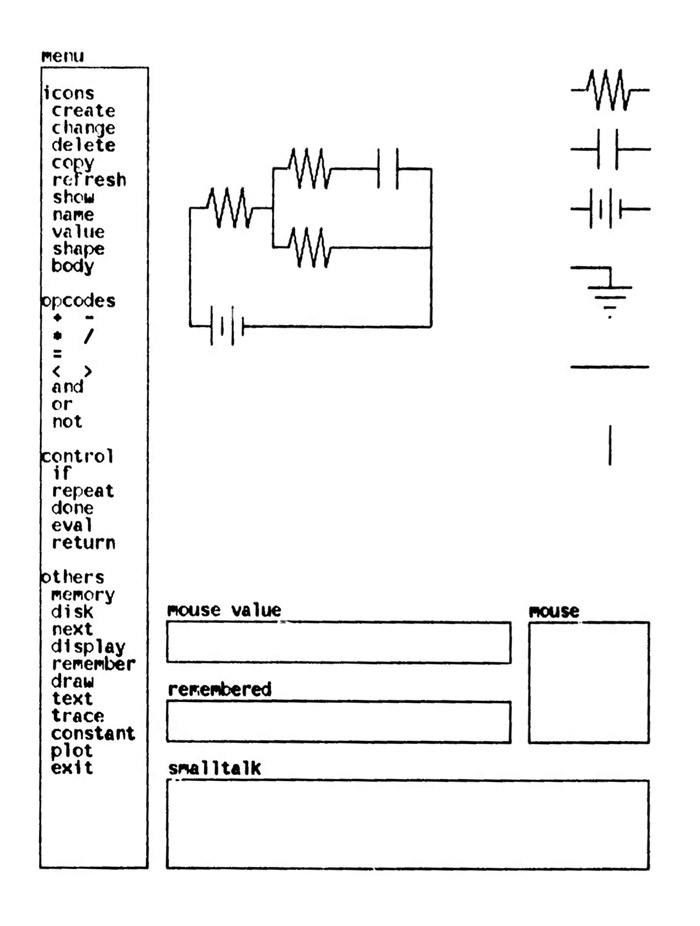

During his PhD, David Smith, created Pygmalion: “A Creative Programming Environment”. He programmed it in smalltalk, an influential programming language created by Alan Kay and Adele Goldberg, Alan kay also being Smith's PhD advisor. Smith's goal was to bridge the gap between art and science, arguing that during the Renaissance, people like Da Vinci were both artists and engineers. For him, creative people, such as designers, should be able to use computers, not only as users of software applications, but rather as programmer themselves. According to Smith, “the main goal of Pygmalion is to develop a system whose representation and processing facilities correspond to mental processes that occur during creative thought” (Smith, 1975). Drawing inspiration from both SketchPad and Genesys, Smith wanted to make programming visual. Smith was especially influenced by the research on creative thinking of his time and he based his design on some concepts borrowed from that literature.

One such notion was incrementation: “[In Pygmalion,] since creativity is incremental, programming proceeds in a step-by-step, interactive fashion, much as one uses an editor to change a body of text”. Pygmalion also introduced a second key idea: the notion of “icon”. Instead of symbols and abstract concepts, Pygmalion uses concrete display images called “icons” to represent abstract notions such as variables or even to save lines of code for later reuse ().

The interface of Pygmalion, “a creative programming environment”

After working on Pygmalion, Smith went on to work at Xerox Parc. As one of the main designer of the Xerox Star computer, he popularized the icons which became a cornerstone of the graphical user interface paradigm that most of our current interfaces derive from.

Sketchpad, Genesys and Pygmalion, all originated in research contexts and were not destined for professional use. In fact, more than tools created to support professional designers work, these projects instead drew inspiration in designers' way of working to transform computers themselves. They introduced novel ways for interacting with computers based on their creators' understanding of creative thinking.

Graphic Design Software

from the Industry Perspective

Most early principles for interacting with computers were invented in universities, but the industry then appropriated them (Myers, 1998). Software dedicated to graphic designers were no exception.

Quantel - PaintBox

In the domain of TV Graphics, Quantel released its PaintBox in 1981 and revolutionized the production of television graphics. PaintBox was a computer graphics workstation, it could only be used for producing animated graphics and its price made it unaffordable for designers who did not work in large companies (). On the other hand, because it was a dedicated workstation, it could handle high quality images and video effects far beyond what was possible with general purpose computers at the time. Following its moto: “crafting the tools that do the job without users needing to know how they work” (Prank, 2011), the PaintBox creators tried to simulate how traditional illustrators worked and to give them the same tools that they were used to work with.

Paintbox, by Quantel, revolutionized animated graphics by mimicking traditional designers tools such as stencils.

Its setup was similar to Genesys, with a pressure sensitive pencil as input and a TV-like monitor as output, so designers could directly paint “on the screen” the way they used to do it on paper. The PaintBox provided tools that mimicked existing illustrator tools such as “airbrushes” and even a color palette where designers could mix color swatches. They also provided “stencils” to let designers separate objects from their background and paint only specific parts of the final image. If Paintbox was hegemonic for TV animated graphics, it was however hardly used by graphic designers whose work was ultimately printed because Paintbox did not handle the necessary resolution.

Mac Write & Mac Draw

The macintosh, release in 1984, launched the era of desktop publishing (Grudin, 2012). For most of graphic designers in the publishing industry, the macintosh was the first computer they encountered (Levit, 2017). Contrary to the PaintBox, it was not specifically designed for them but was instead a general purpose computer.

The Mac Write Interface. The focus of the tool is on writing text, rather than formatting it. The sample text says that it can be used to “write memos, reports, etc.”

The first Macintosh proposed only three general purpose software: Mac Draw, Mac Paint and Mac Write (). Those three software interface principles were direct heir of the Xerox Star, the system that Smith helped to develop at Xerox Parc that established user interfaces mimicking the office paradigm. Before the Macintosh, designers were used to work “blindly”, not seeing what the final output would look like before it came back from the printer. At that time, the traditional process of laying out content, named paste-up, was a very mathematical work, requiring a lot of preparation and calculation as designers had to manually trace guides on their sheet to make sure all their elements were aligned. In contrast, on the Macintosh, graphic designers were able to see the content they were manipulating before printing the final result. Mac applications had adopted the “What You See Is What You Get” paradigm in which designers could change fonts and instantly see the result on the screen. On the other hand, the purpose of Mac Write was to write content as much as to format it. This initial focus influenced the type of formatting functions available, which were limited, from a professional graphic designer point of view. Similarly, influenced by this focus, Mac treated text and image manipulation as utterly different activities, thus separating them in different applications.

Aldus PageMaker

Rapidly, however, a few companies such as Aldus and Adobe, realized that the printing industry would certainly adopt graphic design software if they could allow them to output high quality printed pages. To establish its economic success, design software needed to pursue an apparent continuity with existing environment and techniques (Masure, 2014). In 1985, Aldus released Page Maker (), a Macintosh dedicated software for desktop publishing. This piece of software was, this time, specifically created to supplant traditional technologies and fit within the existing printing industry practices.

The PageMaker Interface

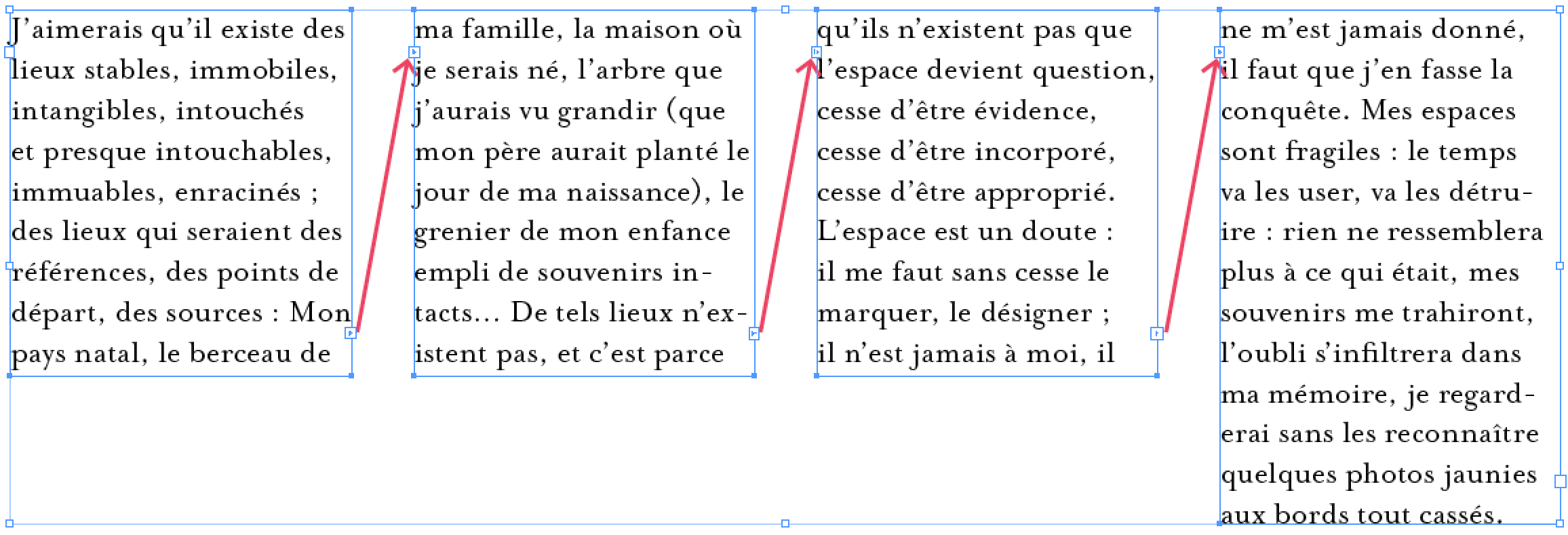

As his founder explains, “most of the page maker interface and dialogs and the way it works, the basic functions came from my experience of having done past up myself with a razor blade” -Paul Brainerd (Levit, 2017). Indeed, Page Maker, and its successors, Quark XPress and Adobe InDesign introduce the possibility to freely drag and drop text onto the page. Moreover, the way desktop publishing software handles text is a reminiscence of the paste-up process that used to be prevalent in the industry: First, designers would do phototypesetting to generate the whole text using the right font at the right size. They would receive single columns scrolls that they would then cut and paste onto the page. In desktop publishing too, as exemplified in (), the text is received as one infinite scroll, it is disconnected from its container. Designers can then compose, cut and adjust the containers. The key difference being that the text continuously flows in the containers, offering greater exploration possibilities to designers.

A second example of the influence of the traditional process over desktop publishing can be found in its way of handling page format. In desktop publishing too, when creating a project, a designer must first select page dimensions as well as margins and a column system. These parameters are then fixed and not supposed to be changed. This echoes the traditional paste-up process in which the designer first chooses a page size and establishes page margins and a grid. This page becomes the canvas onto which she can experiment with text and image positioning. Yet, in desktop publishing, the choice to first set page size and margins is not dictated by a technical constraint, rather, it simply reproduces a pre-existing process.

The influence of Paste-Up can be seen in how InDesign deals with text. Designers can cut and paste the text in separate rectangles

A last example can be found in the type of functionalities enabled by desktop publishing. When presenting their software, PageMakers’ developers explained: “it was designed with the industry in mind, in other words it does half-tones, ligatures, kerning, all the words that the typesetting industry has been familiar with.” (Paul Brainerd, in Computer Chronicles, 1986”). Here again, it is interesting to observe that desktop publishing first and foremost developed functionalities that matched previously existing ones in the industry. In fact, because their goal was to fit within existing workflow and to be easily adopted by designers, they tried to mimick the existing process. Therefore, they proposed very few functionalities that went beyond what traditional processes could produce.

On the other hand, they introduced the WISIWIG paradigm to designers who were previously used to work without seeing the end-result of their production. The conditions and environment behind the emergence of graphic design dedicated software led to the reproduction of pre-existing constraints and principles, coexisting with novel possibilities. László Moholy-Nagy gives a compelling example in another domain: “Square plates would have been more convenient than round ones because they are easier to store. But as the first plates were created from a potter’s wheel, they then went on keeping their rounded shape, despite the new methods [...] that provided total freedom of shape” (Moholy-Nagy, 1973). After the initial standards were established, graphic design software mostly did not change. They gradually added more features but their core functionalities remained the same until now.

Design Software

from a designer perspective

Few graphic designers were able to experiment with computers before the era of personal computers. Yet, this limited access did not prevent a few designers to perceive that computing would transform the way they work.

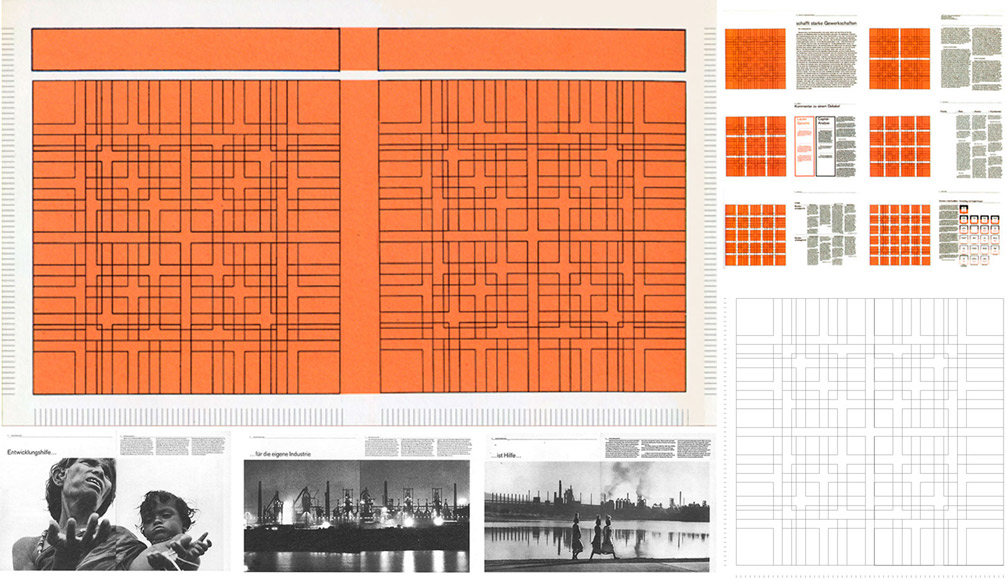

Karl Gerstner - Designing Programs

Karl Gerstner, extract from Designing Programs, 1962.

One of the designers who explored the impact of of computing was the swiss Karl Gerstner (Armstrong, 2009). In his 1968 book entitled Designing Programs, he proposed a manifesto, advocating for a deterministic approach of graphic design. He transposed what he understood from the rigor of computational programs into the typographic grid, turning it into a system (). For Gerstner, the computer was mainly a computational machine that he could use to compute all the potential solutions of a design. The design process thus had to be discretized into a set of parameters in order to make it computable. The designer’s work was then to cast aside all the bad solutions proposed by the computer and, iteratively, to keep the best one. Even if Gerstner was not using design software at that time, he already had perceived the impact that computing could have on the profession: “How much computers change – or can change – not only the procedure of the work but the work itself”. (Kröplien, 2011)

Muriel Cooper

If some designers were able to envision how computers could impact their profession, very few had the chance to work with computers before any of the common interface metaphors became ubiquitous. An almost unknown, yet critical example of a designer who profoundly explored design software tools was MIT professor and graphic designer Muriel Cooper.

“Typography in Space”, an interactive three-dimensional space in which the reader can freely browse, 1994

In her workshop, Cooper sought to explore and extend the influence that graphic design could have on the new digital world. She also explored the influence that computers would have, in return, on the profession of graphic designer. She considered that the “desktop metaphor”, developed since the 1970’s and used in most mainstream applications, was only a transition state in Human-Computer Interaction. (Cooper, 1989)

When she started exploring graphic design with computers, there were no design software. Her students needed to directly program. For her, it was critical that they participate in the creation of their own tools and in exploring their potentialities. As designers were directly involved in the creation of their own tools, the interfaces and interactions created by Cooper and her students were radically different from the ones produced in the research world as well as from the tools that were developed in the industry.

For example, none of Cooper's projects contained the notion of the page. Because this notion did not exist in programming, Cooper and her students were able to think about novel ways to represent information outside of this frame. Instead, they chose to create a 3-dimensional world for displaying information (Strausfeld, 1995). The reader could freely navigate this space to access the information presented on many different 2D planes (). A second example is Perspective, a grid expert system developed in 1989. The system proposes several layouts based on images chosen by the designer and following a simple rule system. Cooper was seeing the computer as a partner for designers who would be designing processes instead of final layouts:

“As applications for multi-media develop, such as electronic documents, electronic mail transactions, and financial trading, the need for automatic layout and design intelligence will be crucial [...]. Designers will simply be unable to produce the number of solutions for the vast majority of variables implicit in real-time interaction. Design will of necessity become the art of designing process.” (Cooper, 1989)

Processing

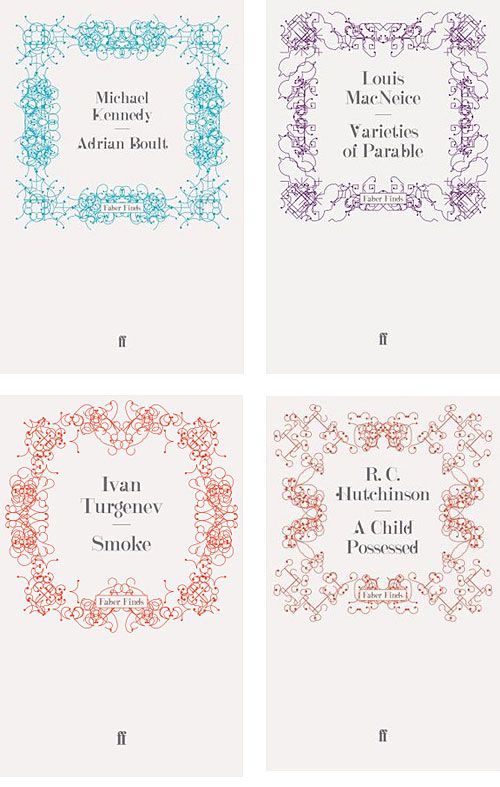

-Faber Finds, Generative book covers, by Karsten Schmidt and Marian Bantjes. Programmed using Processing. 2008

Following Cooper’s approach, John Maeda, one of her students, founded his own workshop: “design by number”. At that time, personal computers had become affordable and graphic design software had appeared. Designers had become users of design software applications created by the industry, rather than creators of their own tools. For designers, learning programming was tedious, because they needed to learn a lot before even being able to display a single square on their screen. To tackle this issue, his students, Ben Fry and Casey Reas, started the Processing project in 2001. Its goal was to make programming easily learnable by designers by emphasizing visual representation. Yet, contrary to Cooper’s approach, they explicitly favored an evolutionary approach, rather than a revolutionary one (Fry, 2009). Built on top of Java, Processing is a simple programming language whose focus is on producing visual and interactive output. Yet, even if Processing is first and foremost a programming language, it also came with a minimalistic Integrated Development Environment also designed to encourage designers to visualize the result of their program as soon as possible. Processing has proved to be extremely influential within the design world, it even sparked a new aesthetic in graphic design (). By giving designers access to programming, it contributed to bringing back discussions about graphic design tools in the spotlight.

Digital design tools created by designers resulted in very different types of tools. Whereas the industry tried to mimick existing design techniques to fit within a pre-existing ecosystem, designers of digital design tools used the opportunity of the digital medium to question the notion of design and to redefine their field.

Design Software -

User perspectives

In the second part of this chapter, I now review the different types of accounts about digital design tools from the perspective of their users. I explore how designers perceive these digital design tools and how they work with them. I review three approaches to this inquiry. I first focus on what a few designers themselves wrote and said about the impact of digital tools on their practices. Empirical studies, mostly from an HCI perspective give us other ways to understand the relationship by observing it in more controlled or longitudinal ways. Finally, I give an overview of different theories that have tried to characterize designers' work with their tools as well as to understand digital tools' underlying conceptions from the perspective of media studies.

Designers accounts

To understand the relationship between designers and their digital tools, we can look at what designers themselves wrote and said. In her documentary Graphic Means: A History of Graphic Design Production, graphic designer and director Levit interviews many graphic designers and shows the spectacular transformations happening in the graphic design industry as computers progressively find their way into designers hands (Levit, 2017). Before the digitalization of the printing industry, graphic design was an entire industry with many different and complementary professions (typesetters, paste-up artists, photomechanical technicians...) coexisting with complex machinery to operate. At a macro level, one of the most crucial transformation brought by computers to graphic design happened off-screen. Because designers could do everything themselves, most of the aforementioned intermediary profession disappeared, leaving all the work in the hands of the designers. This movement greatly empowered graphic designers as their prerogative grew to encompass layout but also type-setting, the art of composing text. It also required designers to acquire new skills. This profound transformation drew a lot of critics from established designers (Armstrong, 2016). The inclusion of computers in the design work also led to a drastic acceleration of the work (Levit, 2017).

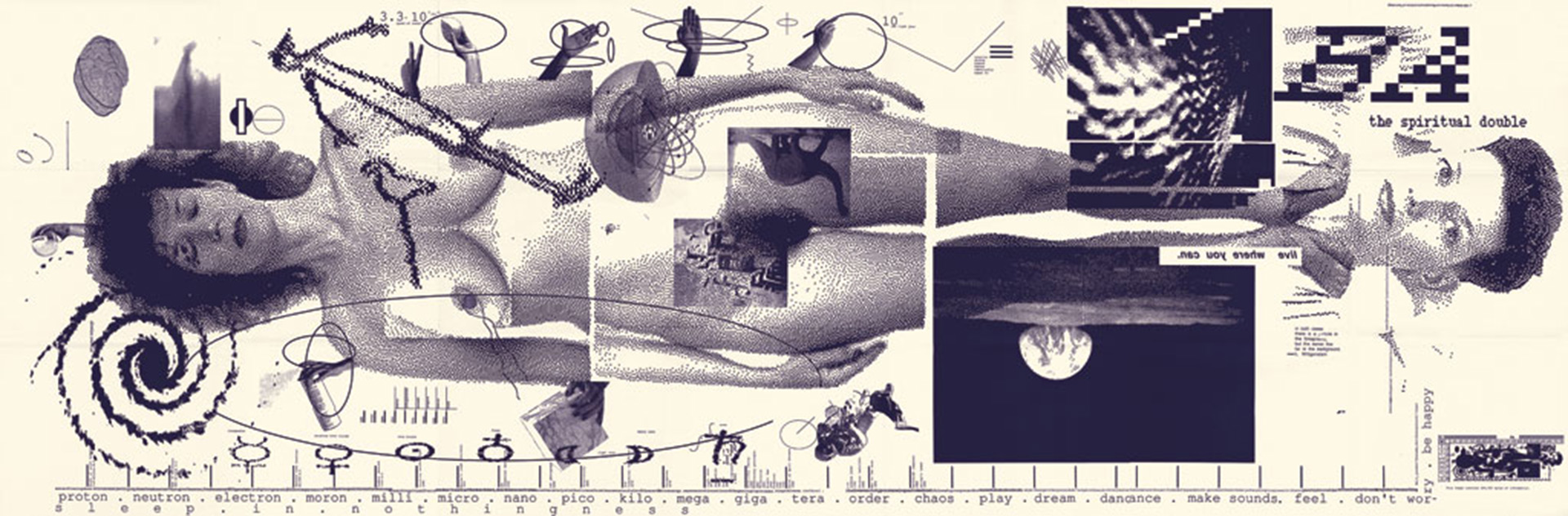

April Grieman - “Does it make sense?”, in Design Quarterly, 1986

At an individual level, we can find evidence of the influence of digital tools by looking at the designs produced when design software applications first emerged. In fact, when personal computers started democratizing software in the 1980’s, they directly fostered a new graphic design era. As graphic designer Cece Cutsforth recalls, “you saw a lot of this whole movement of stuff just being collage, because you finally could” Cece Cutsforth, in Graphic Means, 1:10:50.

One of the first and most famous examples of this revolution was produced in 1986, by April Grieman, with the first Macintosh and MacDraw. She produced a large poster for the 1986 issue of the magazine Design Quarterly (). She found inspiration in the potentiality of the tool, moving away from the very rigid grid revered by many graphic designers at that time. Because of the inherently limited resolution of the dot matrix printer she was using, she accepted and fully embraced pixelization as part of her work. By doing so, she propagated a graphic design revolution, the ‘New Wave’ design style in the US (Armstrong, 2016).

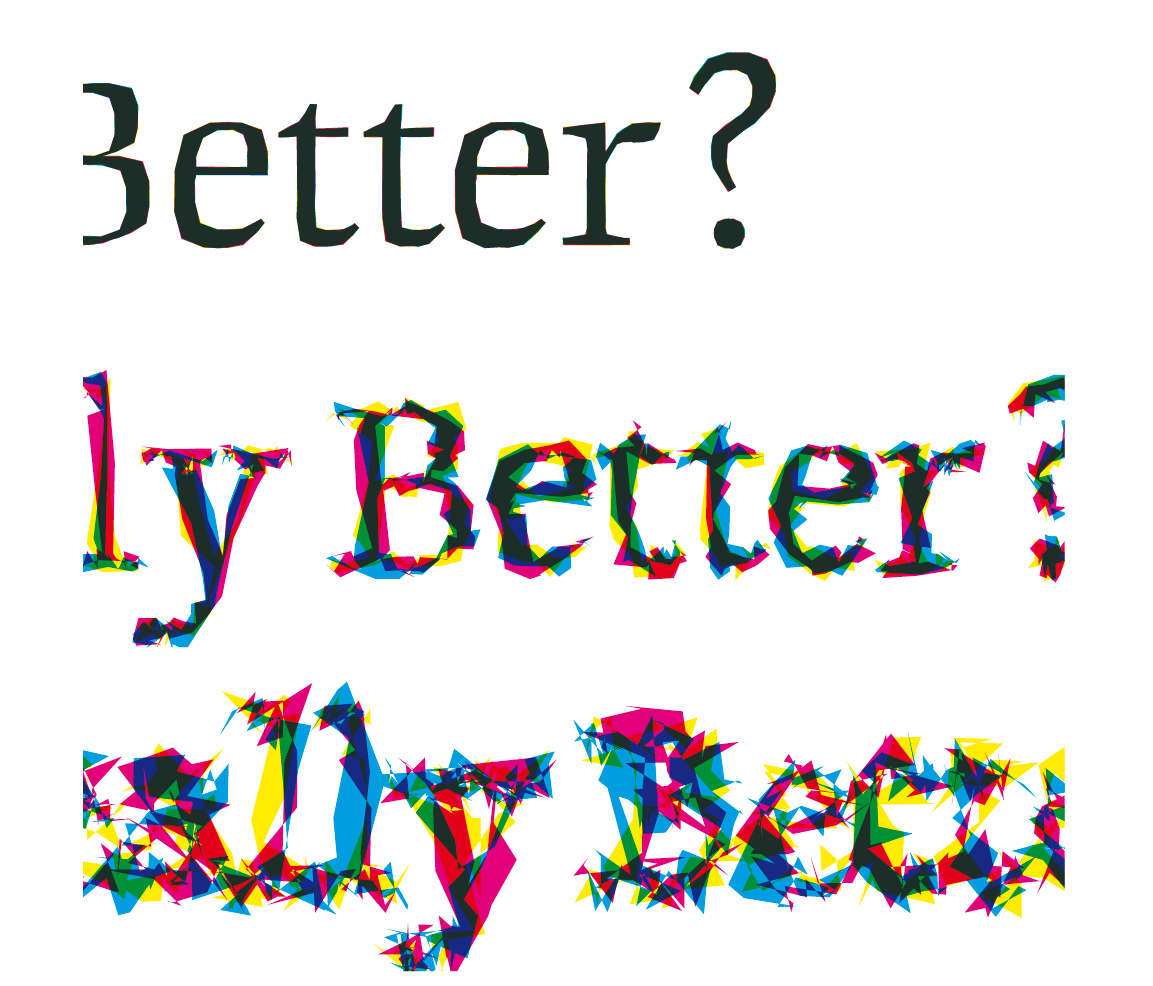

In contrast to Grieman's work, graphic designers Erik van Blokland and Just van Rossum did not see graphic design software as liberating. For them, there is an inherent limitation in the fact that graphic design software is a commercial mass product. It is therefore designed to target a large group of professionals by providing functionalities that are perceived by software designers as the most desired by the community. “You can do everything with a program as long as there are enough people who want to do the same thing. But as it is precisely the task of designers to discover new possibilities, in their case, the use of a computer can be more of a handicap than an advantage. [...] In the long run, this leads to a monotonous computer driven uniformity” (Middendorp, 2004).

Is Best really Better, FF Beowolf font, Erik van Blokland and Just van Rossum, 1990.

Erik van Blokland and Just van Rossum were creating typography in the early 1990's. Each of their new typefaces was designed to explore a specific potential of the computer: “through our experience with traditional typesetting methods, we have come to expect that the individual letterforms [...] should always look the same. This notion is the result of a technical process, not the other way around. However, there is no technical reason for making a digital letter the same every time it is printed” (Middendorp, 2004). To realize their vision of ever different letters, they had to “hack” digital graphic design tools. Instead of using a graphical user interface to draw their Beowolf font, they modified the underlying language, Postscript (). By adding a bit of randomness to the language, Beowolf became a typeface “that changes while it is being printed”. They called their method: “What you see is not what you get”. These two valuable accounts on graphic design during the early age of graphic design software present their authors reflections on design as a field and on their own practice. Yet, because their target audience is generally other designers, these documents provide relatively little information on the concrete practice of design with digital tools.

Empirical Account

Empirical studies are a second way to apprehend designers' relationship with their digital tools. As early as 1967, Cross conducted a study with designers to figure out what the design requirements for Computer Aided Design systems might be as well to evaluate the impact of such systems (Cross, 1967). At that time, only a few years after Sketchpad's major breakthrough, fully functional CAD systems were still hypothetical. To simulate what they might look like, Cross coined a simulation technique, close to the “Wizard of Oz” technique (Cross, 2001), in which human beings pretend to be computers. Because design software did not exist at that time, practitioners did not know what to expect from such systems. Cross conducted a first series of 10 experiments, giving a design brief to designers and asking them to produce a sketch concept with the help of a simulated CAD system. They could interact with it by writing message on paper and showing them to a camera and they would receive answers on the screen. Cross’s goal was to observe how they would choose to interact with such a system, hoping to extract requirements for building future CAD systems. The first results were not positive as using the CAD system induced stress on the designers part and didn’t result in better designs. Cross explored an alternative version of the experiment by asking the system (or rather the human behind the curtain) to create the design while the designer was judging the results. This version was more enjoyable for designers but required the CAD system to be able to design, which, as Cross tested in later experiment, did not work so well (Cross, 2001).

Years later, in the 1990’s, as design software were becoming more and more common in design agencies, a few studies investigated their impact on graphic design agencies and publishing companies. For example, Bellotti and Rogers (Bellotti, 1997) conducted a six-month field study to investigate “the changing practices of the publishing and multimedia industries”, focusing specifically on the multiple representations at play and on the relationships between computers and the other artifacts used by designers. They emphasize the “continuous switching between representations” of the same content and advocated for tools to better integrate the paper-based methods and “electronic technologies”. Similarly, Diane Murray conducted an ethnographic study of graphic designers in 1993 (Murray, 1993). She revealed how material traces are interwoven with the social aspect of a design studio life. Designers leave visible their sketches and work in progress so that anyone can look at them and enrich them by critiquing them. In 1995, Sumner conducted an ethnographic study of user interface designers working with digital tools (Sumner, 1995). She witnessed the evolution of tooling environment and practices at a time when software were quickly appearing and changing. She realized that designers were creating what she calls Toolbelts, a collection of several tools supporting their different practices. Designers did not simply used the tools, but appropriated them and re-purposed them for specific activities. She also showed how “a large part of these designers’ job is ‘designing their design process’” (Sumner, 1995). These different ethnographic accounts demonstrate the complex interplay between designers, computer tools and corporate needs. They however focus mainly on the relational aspects of design work but give us little detail on how concretely designers work with their digital tools.

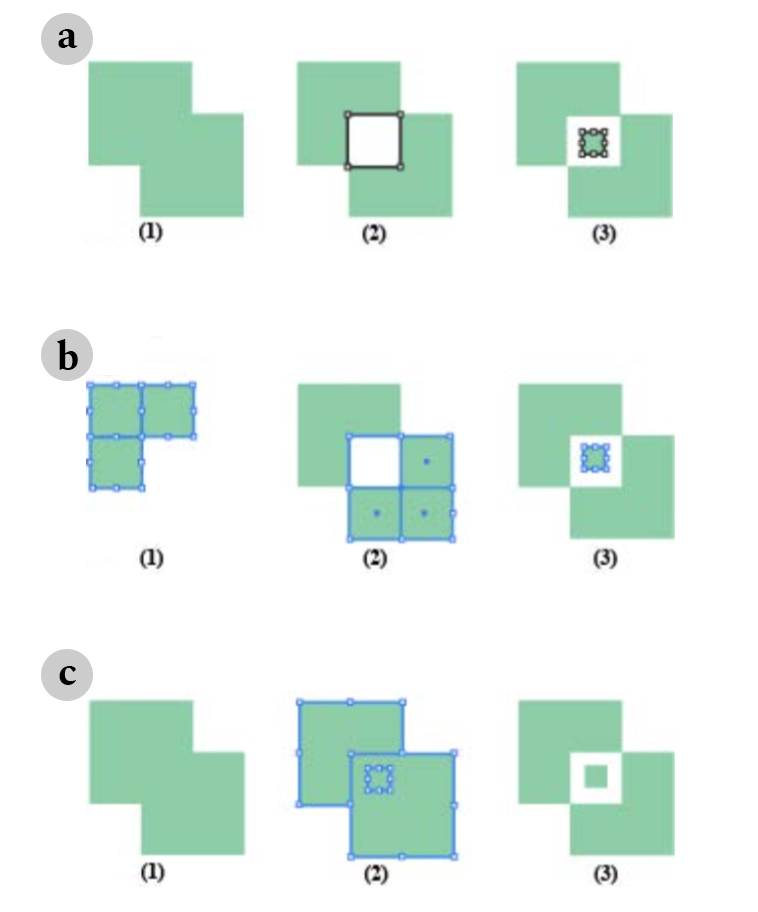

Three visual composition strategies for the same visual composition task, in (Jalal, 2016)

More recently Jalal conducted a structured observation (Jalal, 2016) with 12 designers to investigate the different tools and strategies used by designers to reproduce a poster in Adobe Illustrator. She discovered that, to achieve the same result, designers would deploy a wealth of strategies and tools (). For example, one of the tasks was to cut 12 rectangles into triangles. Among the 12 designers, she observed eight different strategies to achieve this effect. Even when the software had built-in dedicated tools, designers tend to rely and prefer tools that allowed them a more direct manipulation of graphical elements. Moreover, she was surprised by how often designers would reflect on their strategies, either considering them as “clever tricks”: strategies that they would reuse in the future, or “bad hacks”: strategies that they used as a way out but did not consider proper ways of achieving the result. This lab study highlights the richness and variety in designers’ individual interaction with tools, even within the same application.

Yet, we still have very little knowledge on how designers design with and around software. Bellotti and Rogers, in 1997, were already advocating for more studies to understand how designers work with design software applications (Bellotti, 1997). We also start seeing evidence that designers don’t passively use software. With this thesis, we focus on understanding designers’ relationship with their digital tools in the wild, focusing on extracting principles that could help us inform the design of design tools.

Theoretical accounts

To understand designers relationship with digital tools, we can look at the different theories that tried to explain it. In HCI, design researchers often draw inspiration from Schön’s influential book: The Reflexive Practitioner. How Professionals Think in Action to explain how designers work. According to Schön, designers have what he calls “reflective conversation with the situation” (Schön, 1984). From a set of observations with architects, psychotherapists and systems engineers, Schön demonstrates how they approach problems as unique cases and focus on the peculiarities of the situation at hand. They don’t propose or look for standard solutions. Instead, Schön argues that “in the designer’s conversation with the materials of his design, he can never make a move which has only the effects intended for it. His materials are continually talking back to him, causing him to apprehend unanticipated problems and potentials” (Schön, 1983). Dalsgaard further explores the pragmatist perspective to consider tools in design as “instruments of inquiry” (Dalsgaard, 2017). He argues that tools also affect our perception and understanding of the world and help us explore and make sense of it. He proposes a framework for understanding the role tools play in design, with five qualities for “instruments of inquiry”: perception, conception, externalization, knowing-through-action and mediation. The perception of digital design tools as instrument is also developed by Bertelsen & al. Originally proposed in the context of musical creation, they introduce the notion of instrumentness as a “quality of human-computer interaction” (Bertelsen, 2007). They propose to consider creative software as instrument in the musical sense, to be able to move away from the ideals of transparency and usability. They argue that “the software is comparable to a musical instrument since the software becomes the object of [the composer's] attention and something he explores, tweaks, observes, and challenges in a continuous shift of focus between the sounding output and the instrument”. They argue that the notion of instrumentness can be adapted beyond music creation and be relevant to describe designers relationship with their digital tools.

“Default Workspace”, Anthony Masure, 2013

Outside of the HCI literature, the emerging field of media and software studies attempts to explore the underlying assumptions behind design software. In 2003, professor of cultural studies Matthew Fuller explored the principles behind authoring software (Fuller, 2003). Taking Microsoft Word as an example, he highlighted the dissonance between creative activities and the task oriented way in which authoring software application were built on. According to Fuller, they embed a very specific notion of work borrowing from Taylorism, where human actions are decomposed into minimal tasks. He remarks, for example, that the use of templates and wizards makes it very easy to create certain types of work-related documents, such as letters and CVs, while some others (suicide notes, for example) do not receive the same attention. To better understand the logic behind software, he proposes to look at the missing features of Word: “For instance, which models of “work” have informed Word to the extent that the types of text management that it encompasses have not included such simple features as automated alphabetical ordering of list or the ability to produce combinatorial poetry as easily as “Word Art”? (Fuller, 2003). Focusing on design-oriented authoring software, media researcher Lev Manovich, differentiated traditional media production and what he called “new media” production (Manovich, 2001). According to him, design software exemplify a new paradigm: “the logic of selection” within menus of actions and filters. He argues that media produced with current digital design software applications are rarely created ex nihilo, they are “collage of existing elements” assembled from menus. In his PhD dissertation about the design of software, Masure shows how new versions of Adobe Photoshop add functionalities that are in fact specific automated functionalities, for example, automatically replacing objects on a photograph with a generated background in Photoshop CS5 (). He argues that this type of functionalities is meant to simplify the work of the designer by automatizing it. In doing so, Masure argues that “the semi-automatic functionalities orient the image towards a state that is socially and culturally accepted” (Masure, 2014).

Summary

This chapter explores the history of design software from the perspective of those who created them as well as those who used and analyzed them. In the first section, I analyze the history of design software, focusing on how their condition of creation affected their design. I introduce how design software were produced from three complementary perspectives. The first one are design software created as HCI experiment by computer scientists. The second one, in the context of graphic design, came later and sought to replace traditional, analog, graphic design tools. The third path are design tools created by graphic designers themselves and that sought to reinvent what graphic design meant. In the second section, I explore how designers perceive these digital design tools and how they work with them. Designers themselves wrote about the impact of digital tools on their work during the early days of computers. They demonstrate how, from their origin, digital tools were both seen as empowering and limiting. Empirical studies, mostly from an HCI perspective give us other ways to understand the relationship by observing designers daily work with computers in more controlled ways or in longitudinal studies. They reveal the complex interplay between on-screen and off-screen design work. Finally, I give an overview of different theories that have tried to characterize designers' work with their tools as well as to understand digital tools' underlying conceptions from the perspective of media studies. These three different perspectives all show the intricate interplay between designers and their tools. However, we still lack an empirical understanding of designers daily practices with their digital tools, from very specific tasks to more global endeavors.

Studying Designers

If our goal is to create digital tools for designers, we must investigate designers’ daily practices with current design software. We need to understand how designers work with and around digital design tools: how do they appropriate and adapt them for their specific needs? We also need to understand to what extent current design tools support these practices. Tools play a key role in any given creative process (Bertelsen, 2007) and it is difficult to decouple and analyze a creative process without taking into account the different tools that support it. I chose to study designers’ relationships with their digital tools through the angle of designers’ practices: instead of looking directly at how designers use particular tools, I focus on how designers carry specific design tasks and observe alongside how they integrate digital tools as part of their strategies. To do so, I chose four specific and concrete specific design tasks within overall design projects.

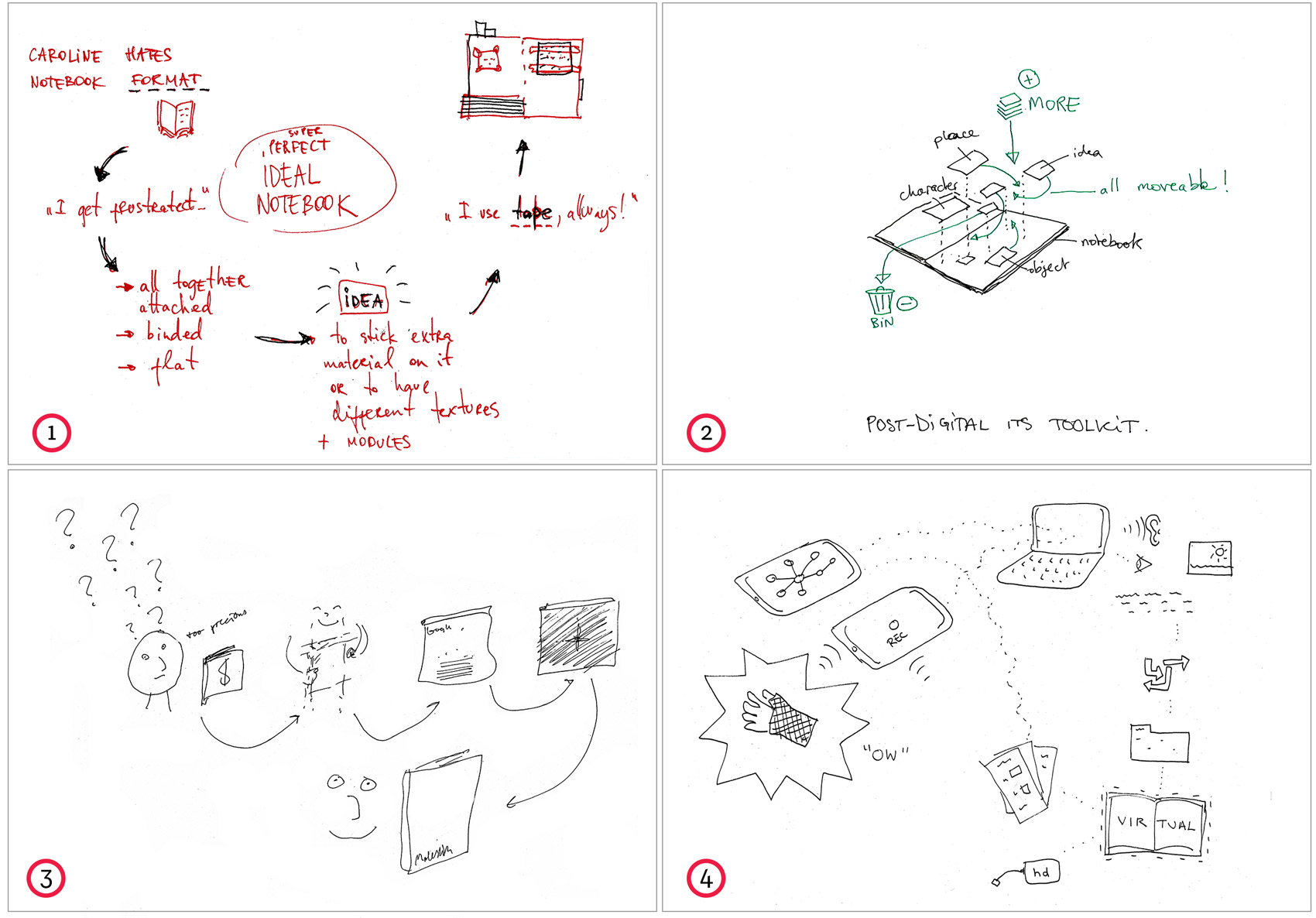

In the following chapters, I present the results of four complementary projects investigating design tasks at different levels of complexity. I chose them because their different scales would allow me to look at design tools from very different points of view and, hopefully, reveal both different and common traits across design task scales. I first started with extremely specific practices: color selection as well as alignment and distribution. Both these practices are currently supported by dedicated tools, namely the color selector and the alignment and distribution commands. Moreover, these two tools are included in all mainstream design software. To complement these first two inquiries, I turned to a more complex graphic design task: layout structuring. This practice has long been associated with a well established conceptual tool, namely the grid (Williamson, 1986). Yet, it is indirectly implemented through several features in common graphic design software tools. Finally, I inquired into designers collaboration practices with developers. By definition, this practice takes place at the verge of design software tools, as designers need to give their design to developers for them implement it in their own tools.

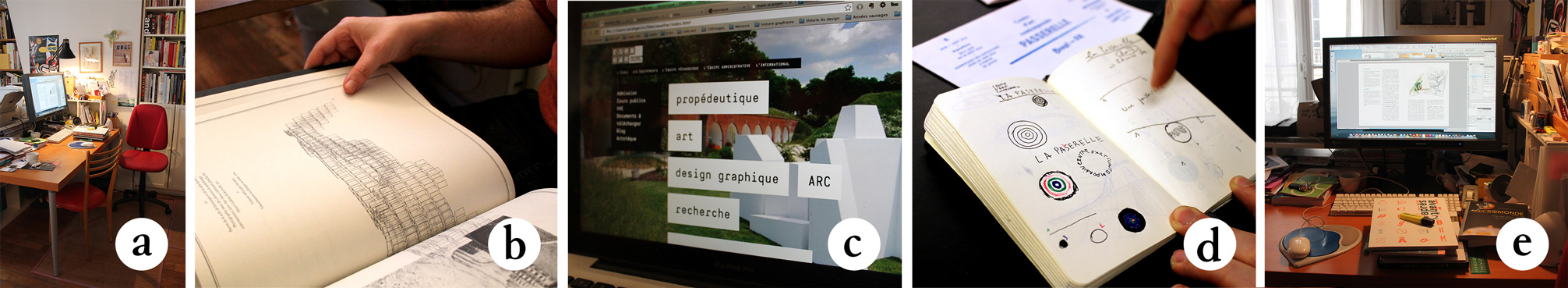

To study such a wide variety of design activities, I felt the need to establish a dedicated methodology. Artists and designers themselves find it difficult to describe their process. This is what epistemologist Michael Polanyi calls “the tacit dimension” of practice (Polanyi, 1966). Because I am focusing on the material aspect of the design process, I designed and introduced a methodology to elicit and document designer’s practices, taking into account the material aspect of their work.

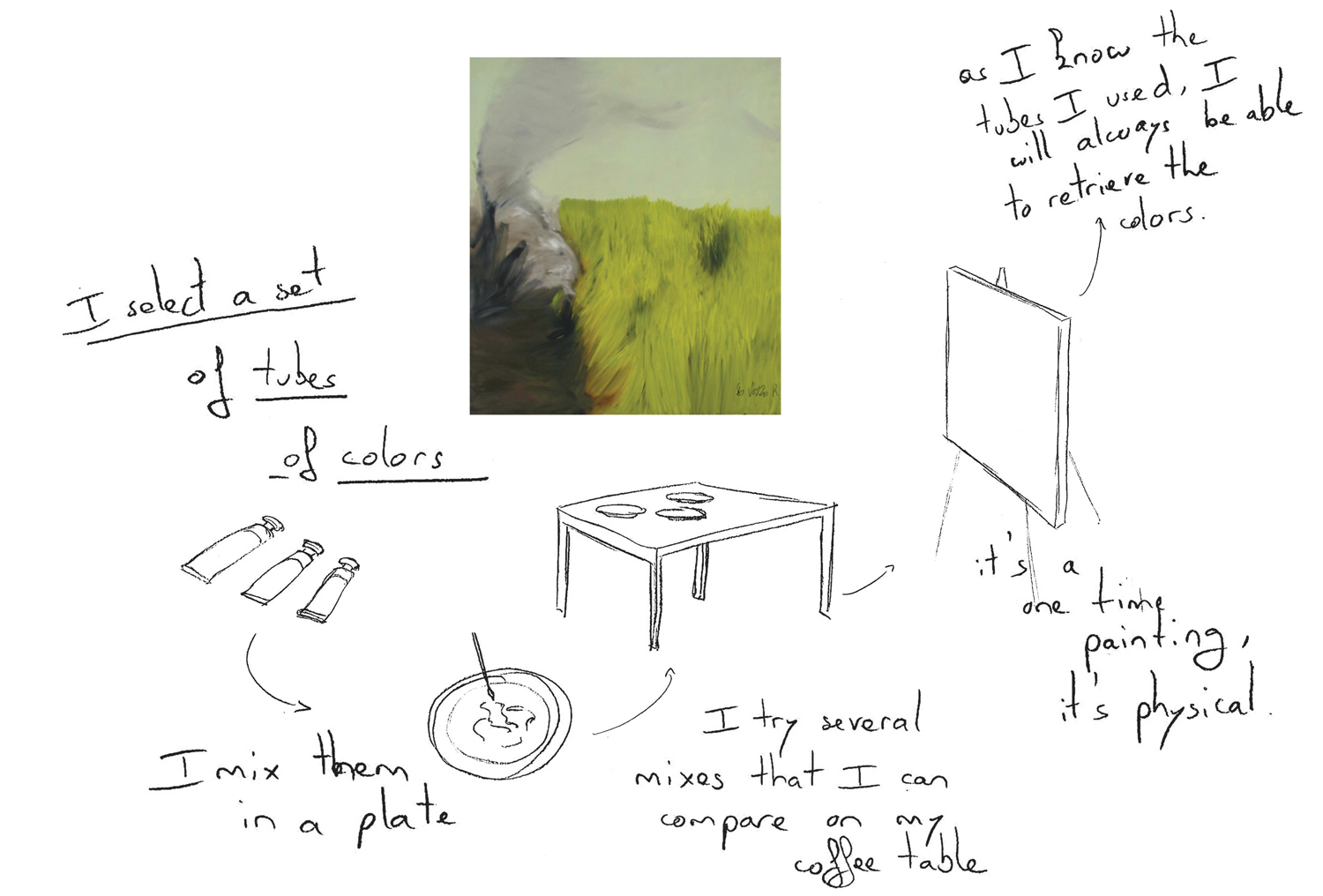

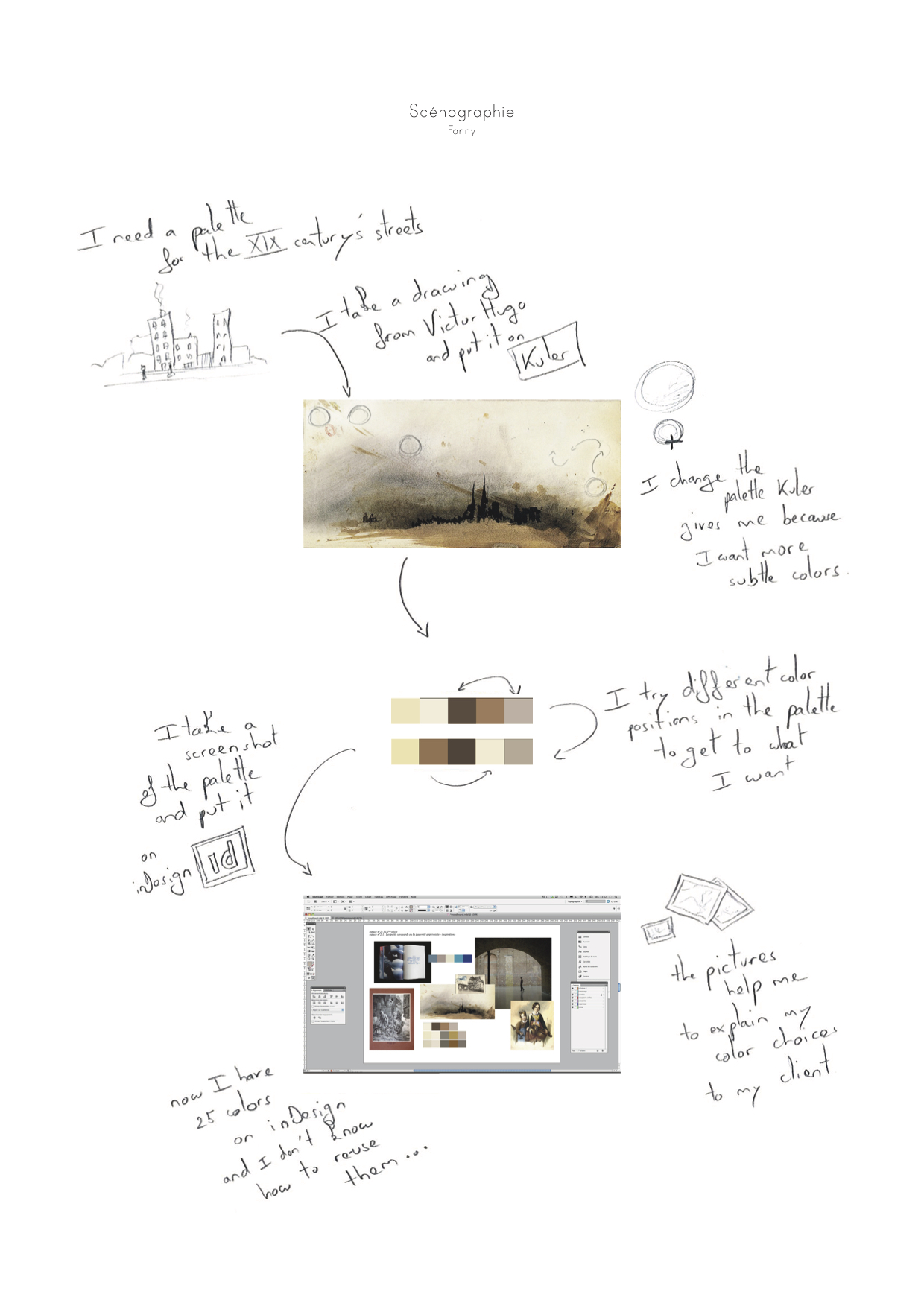

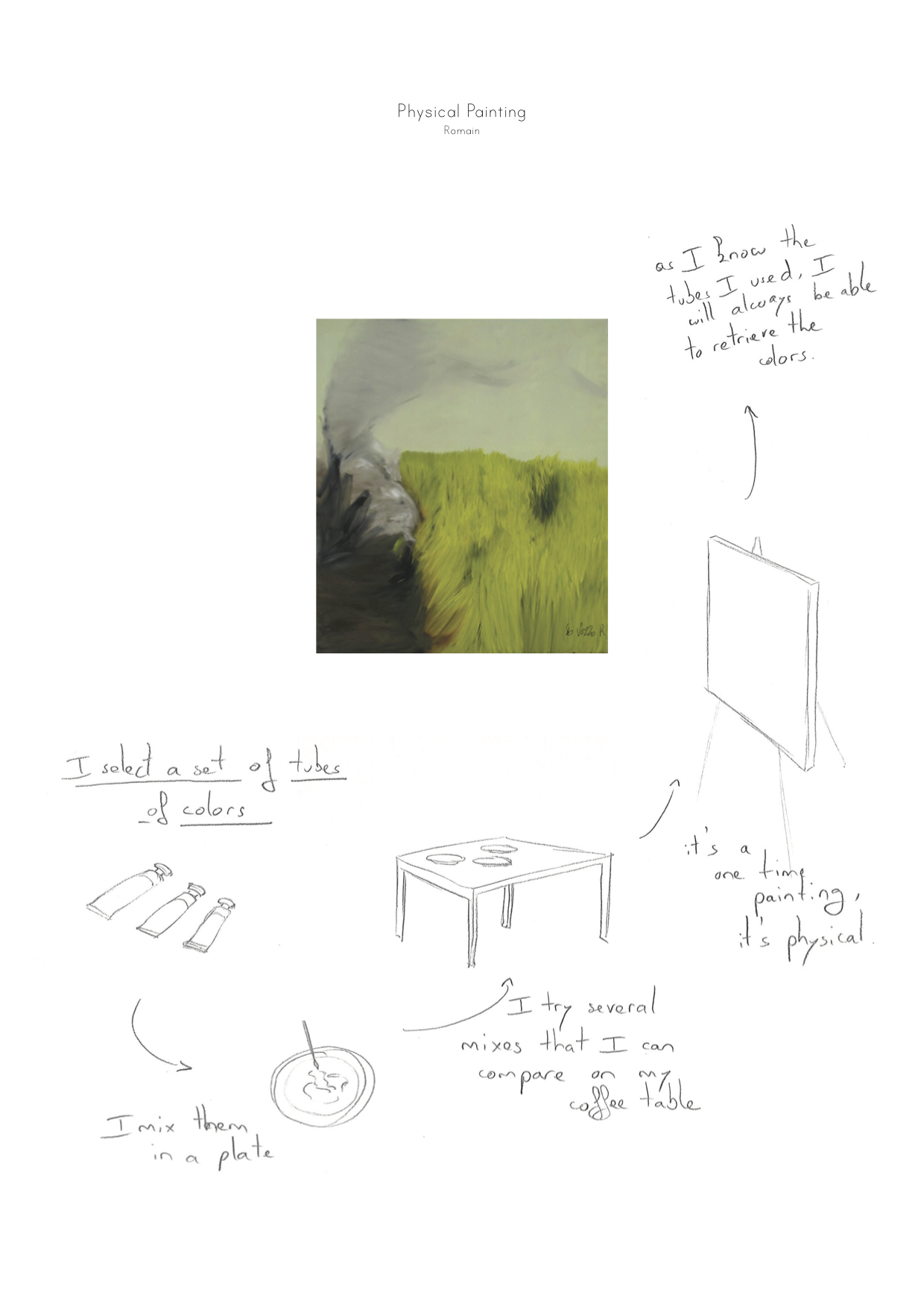

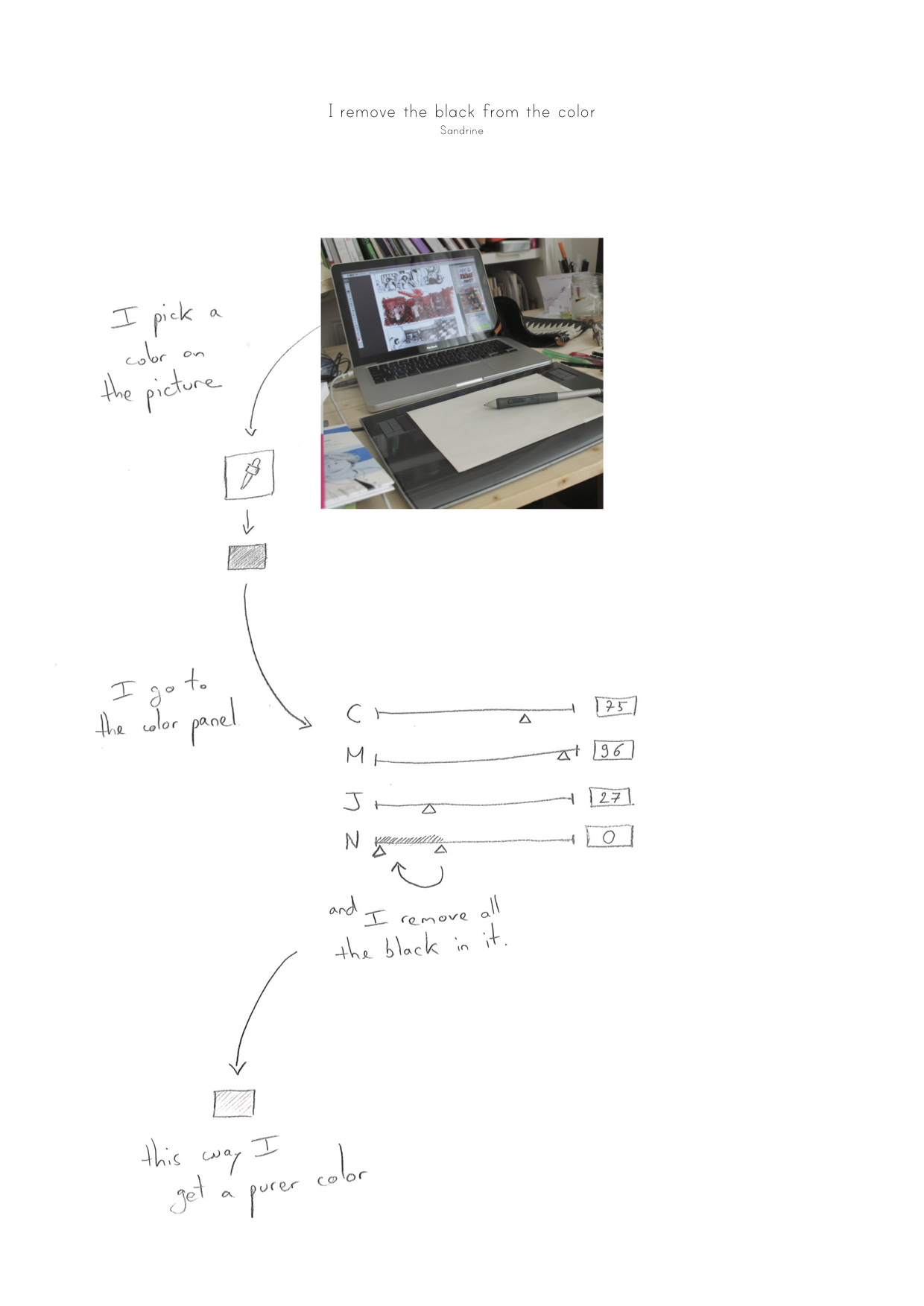

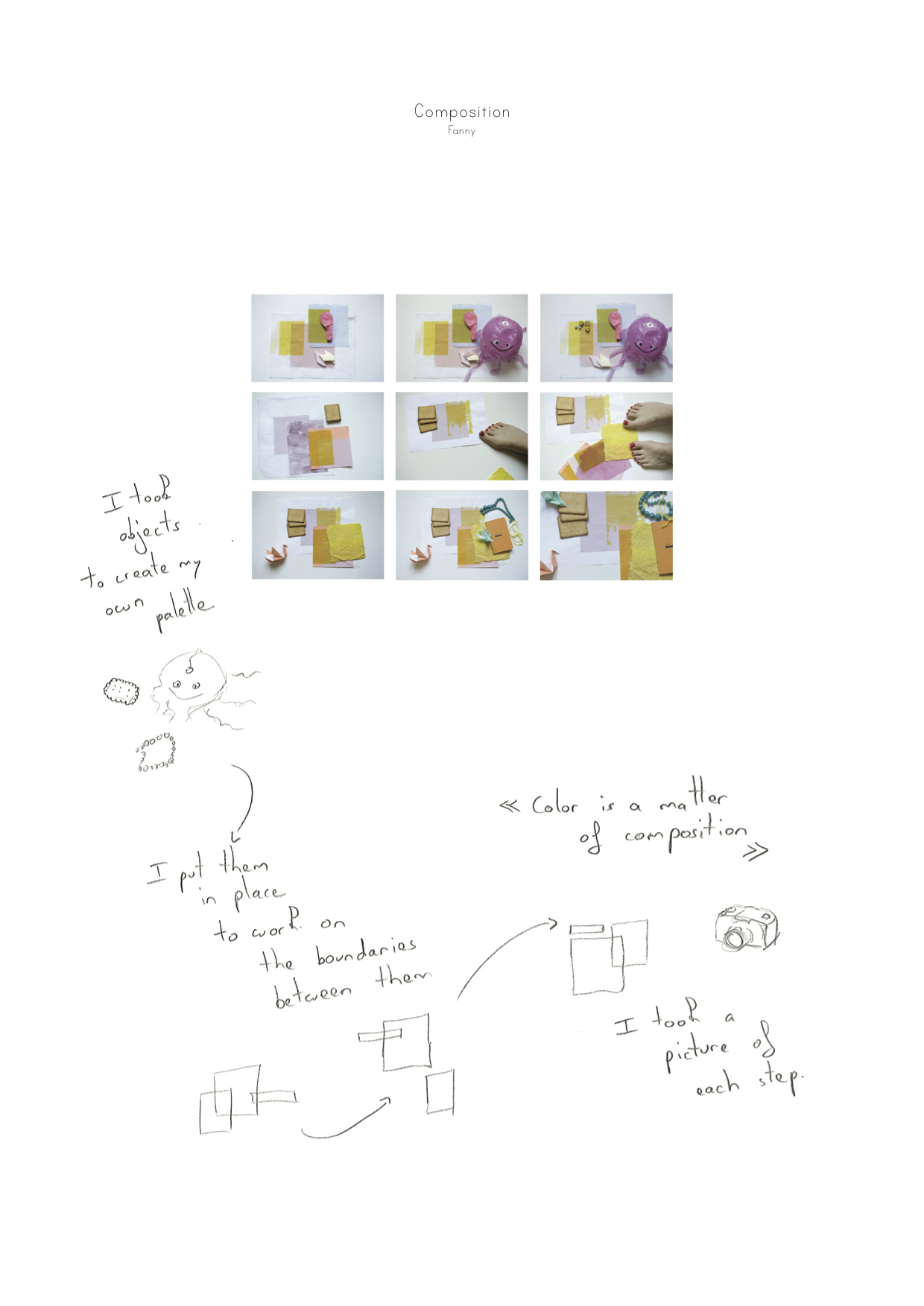

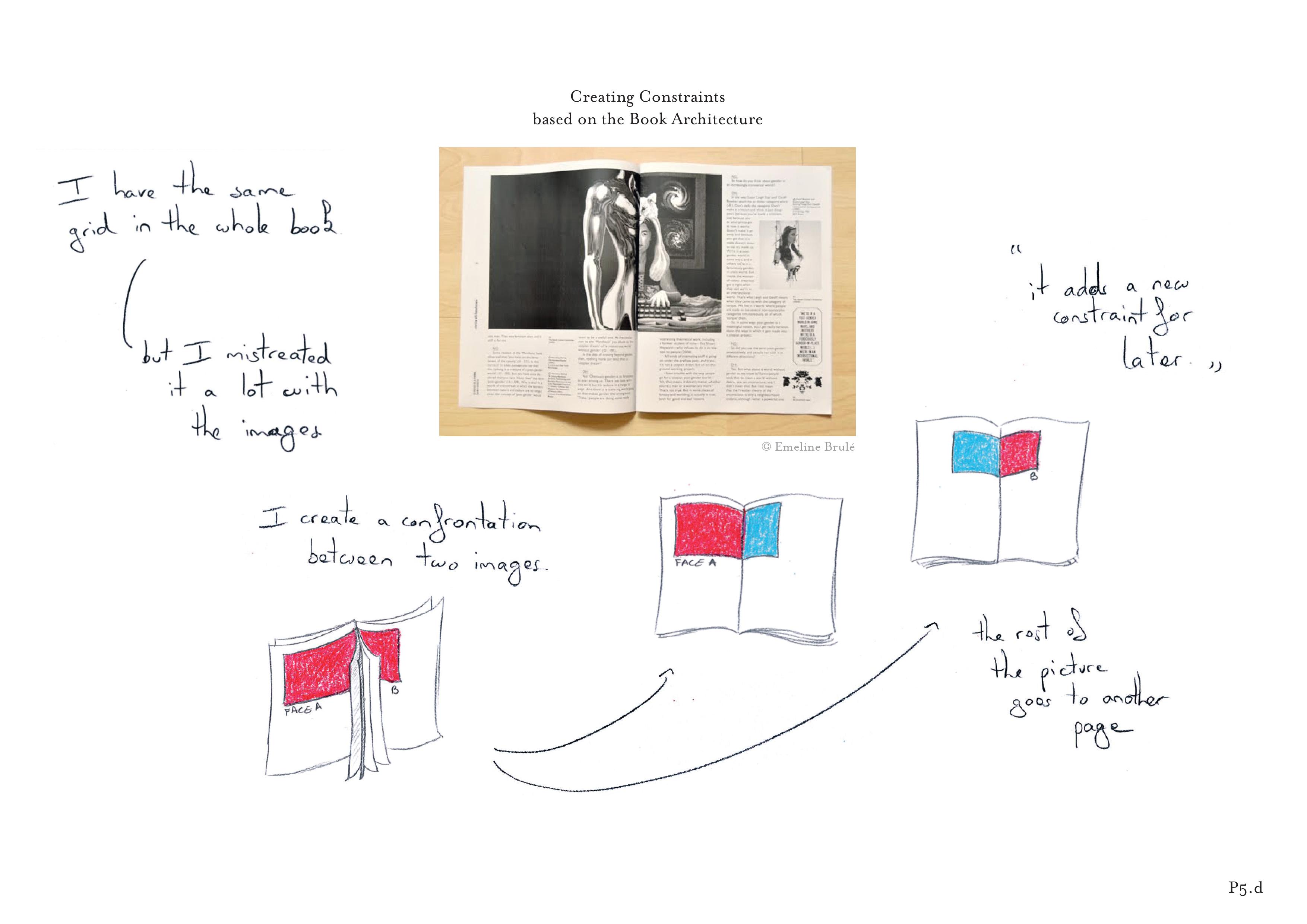

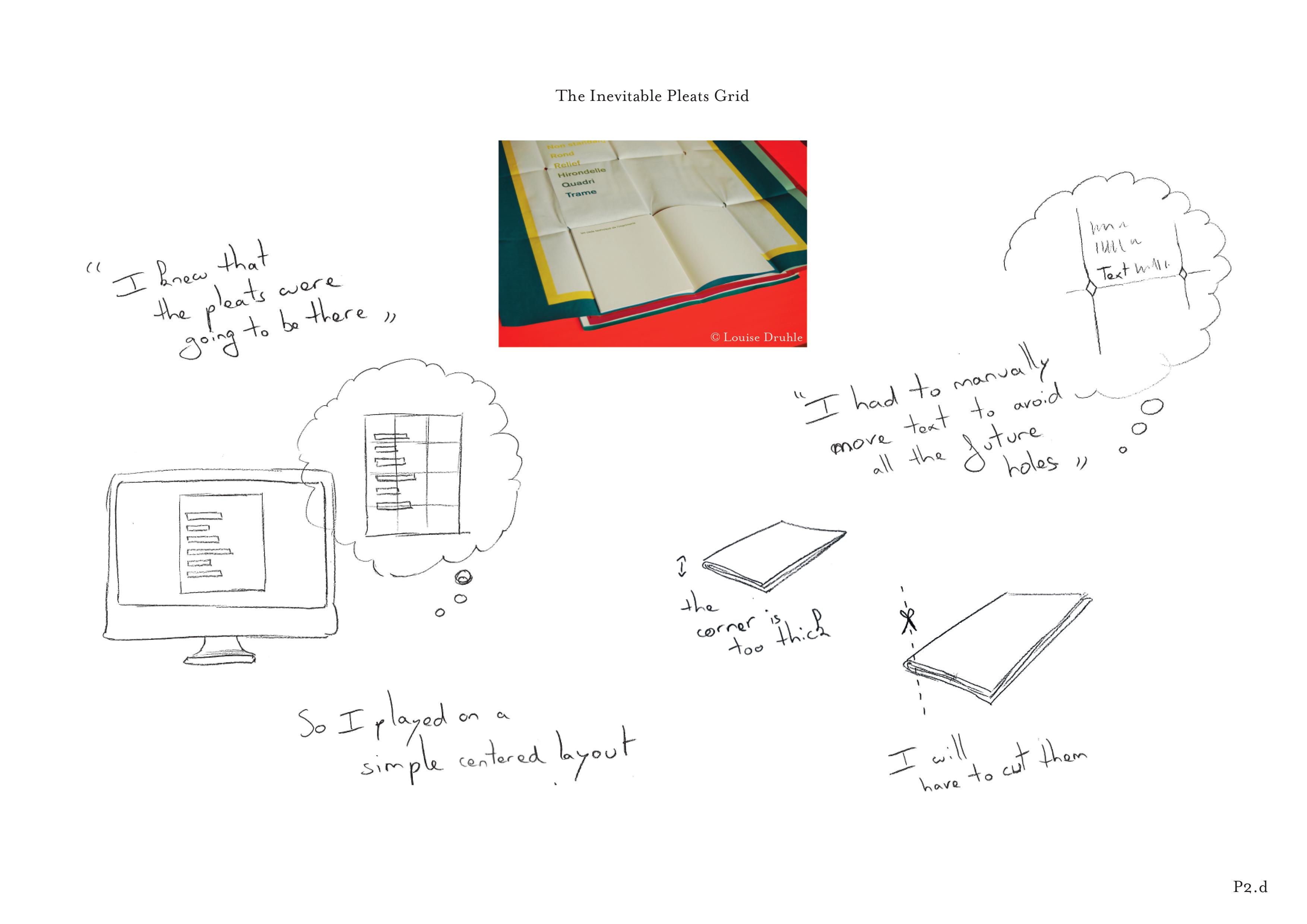

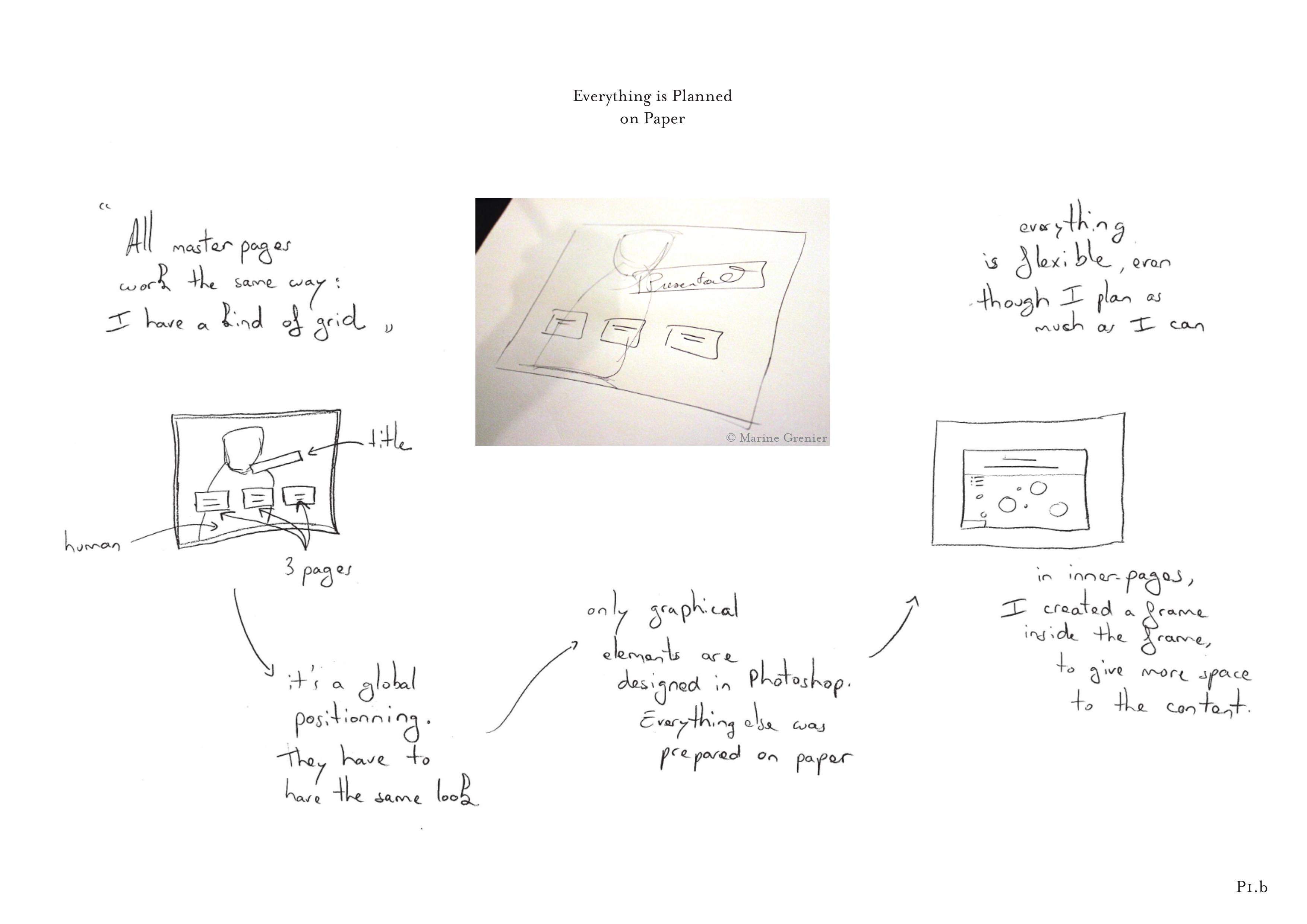

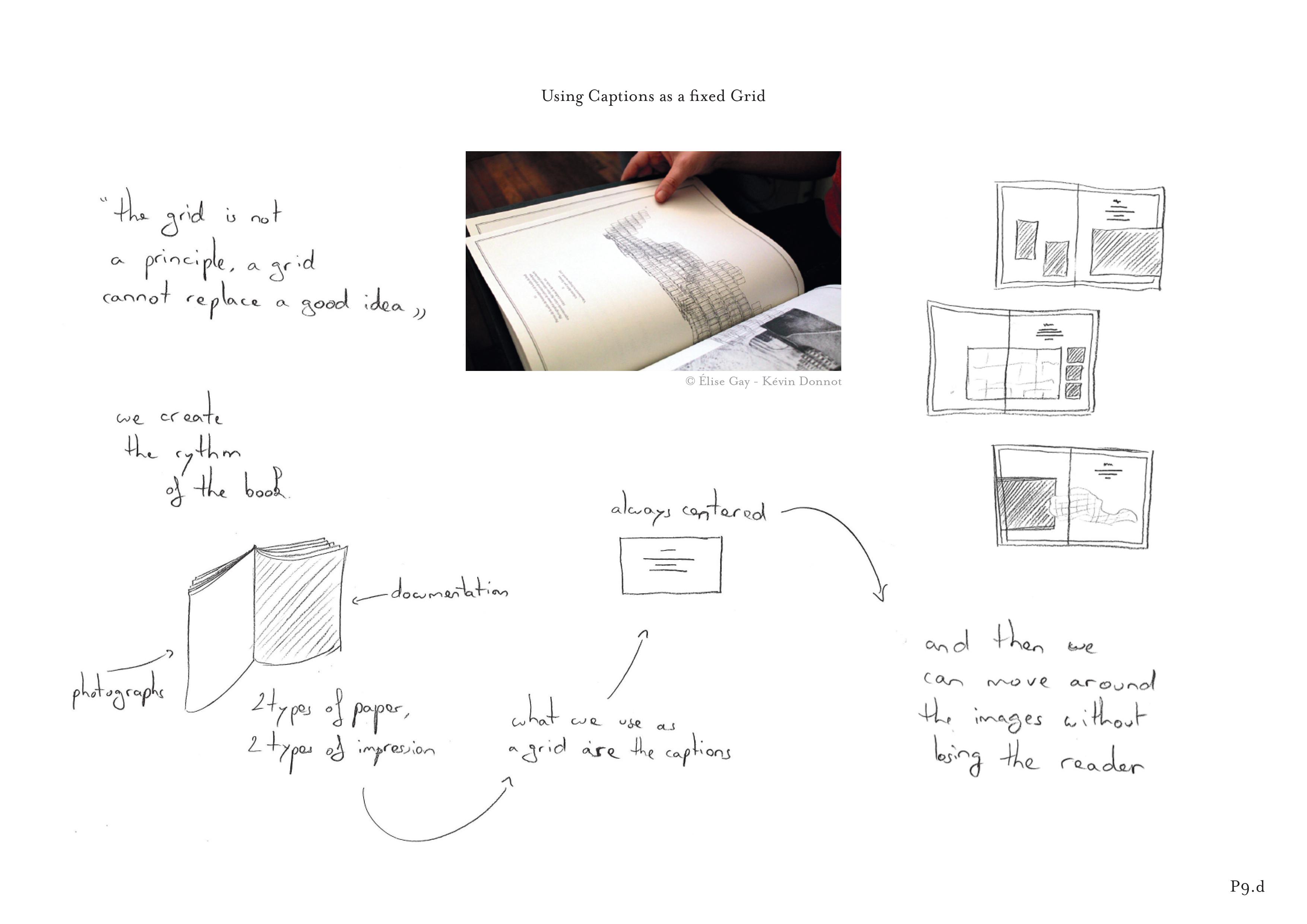

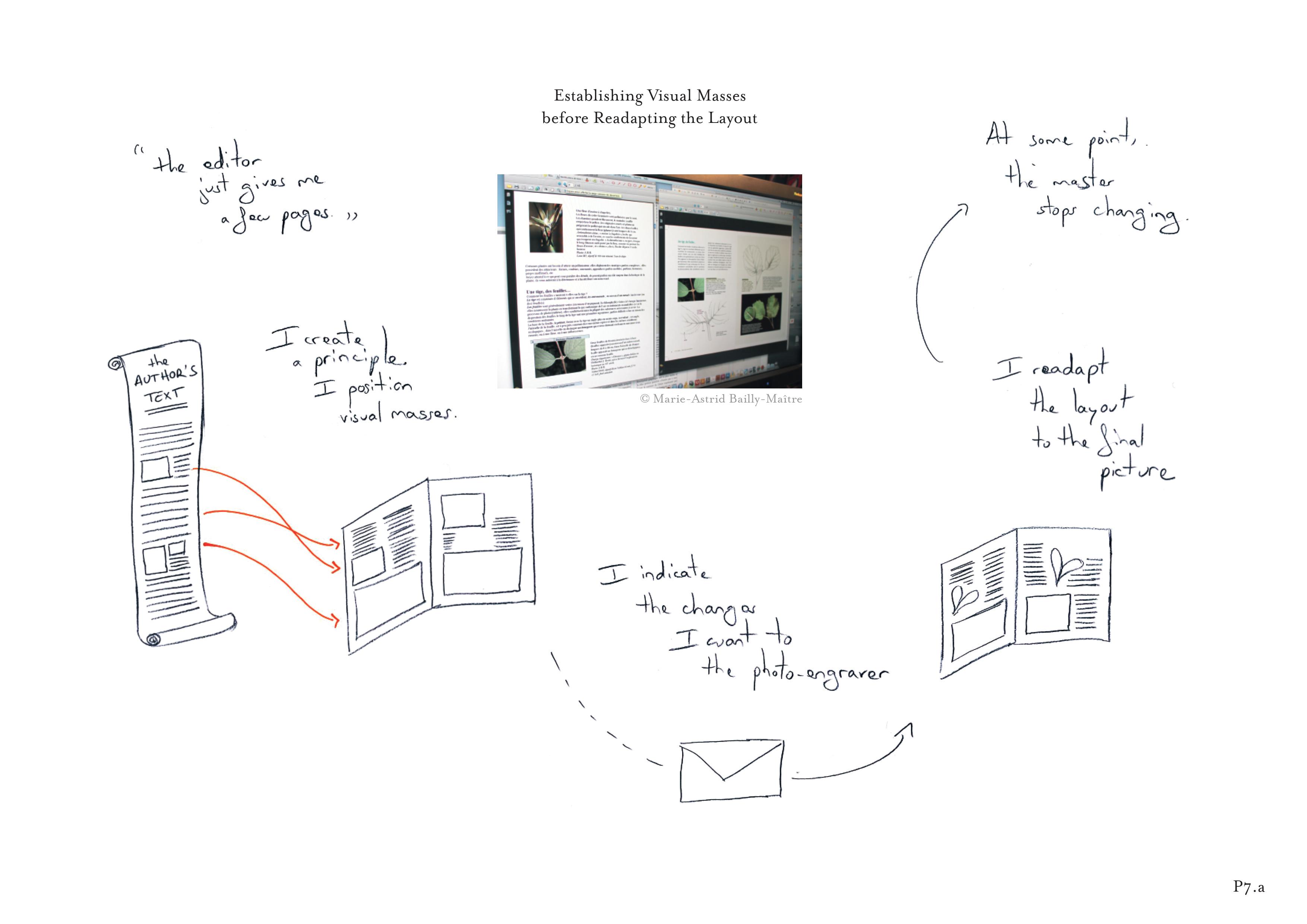

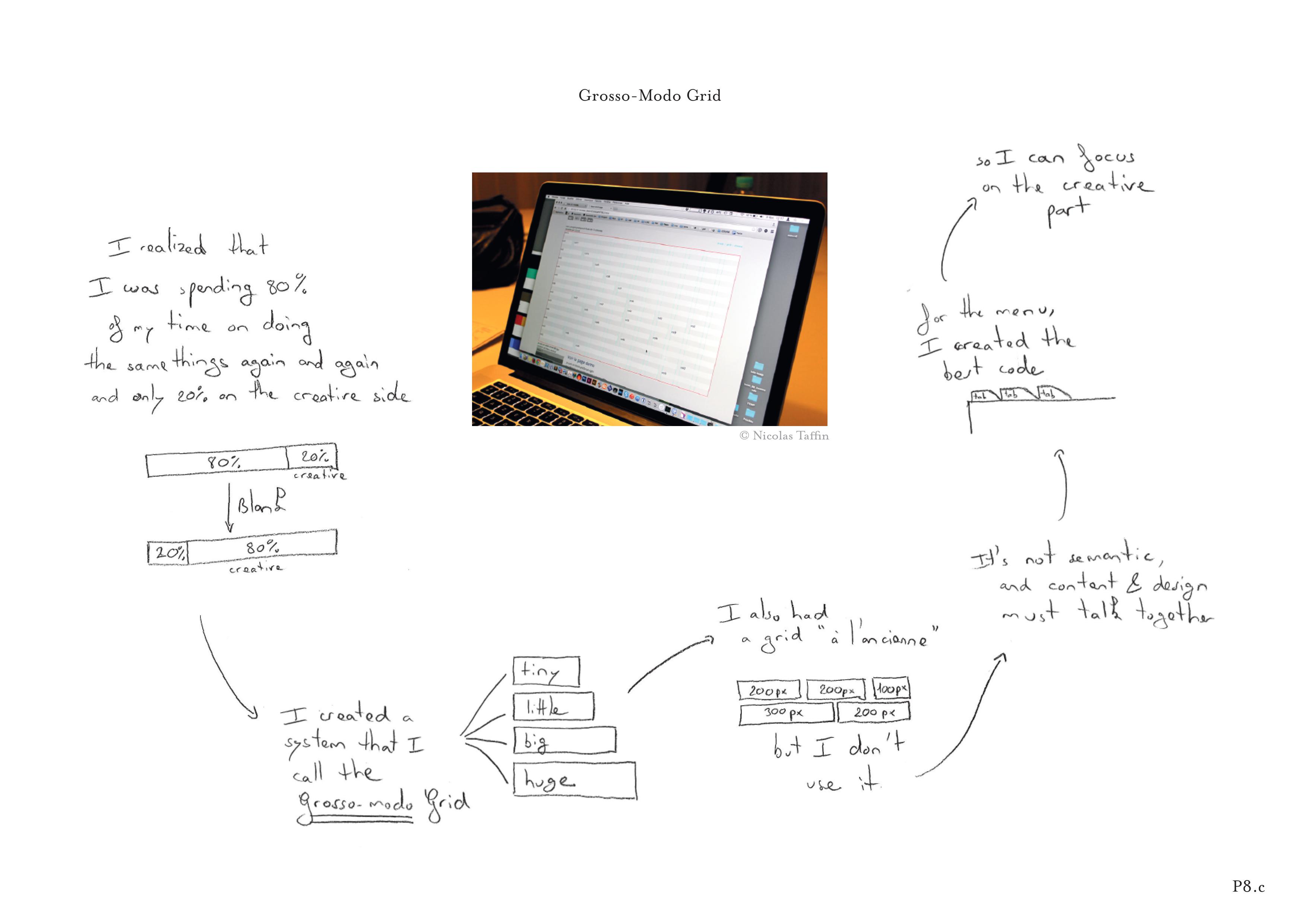

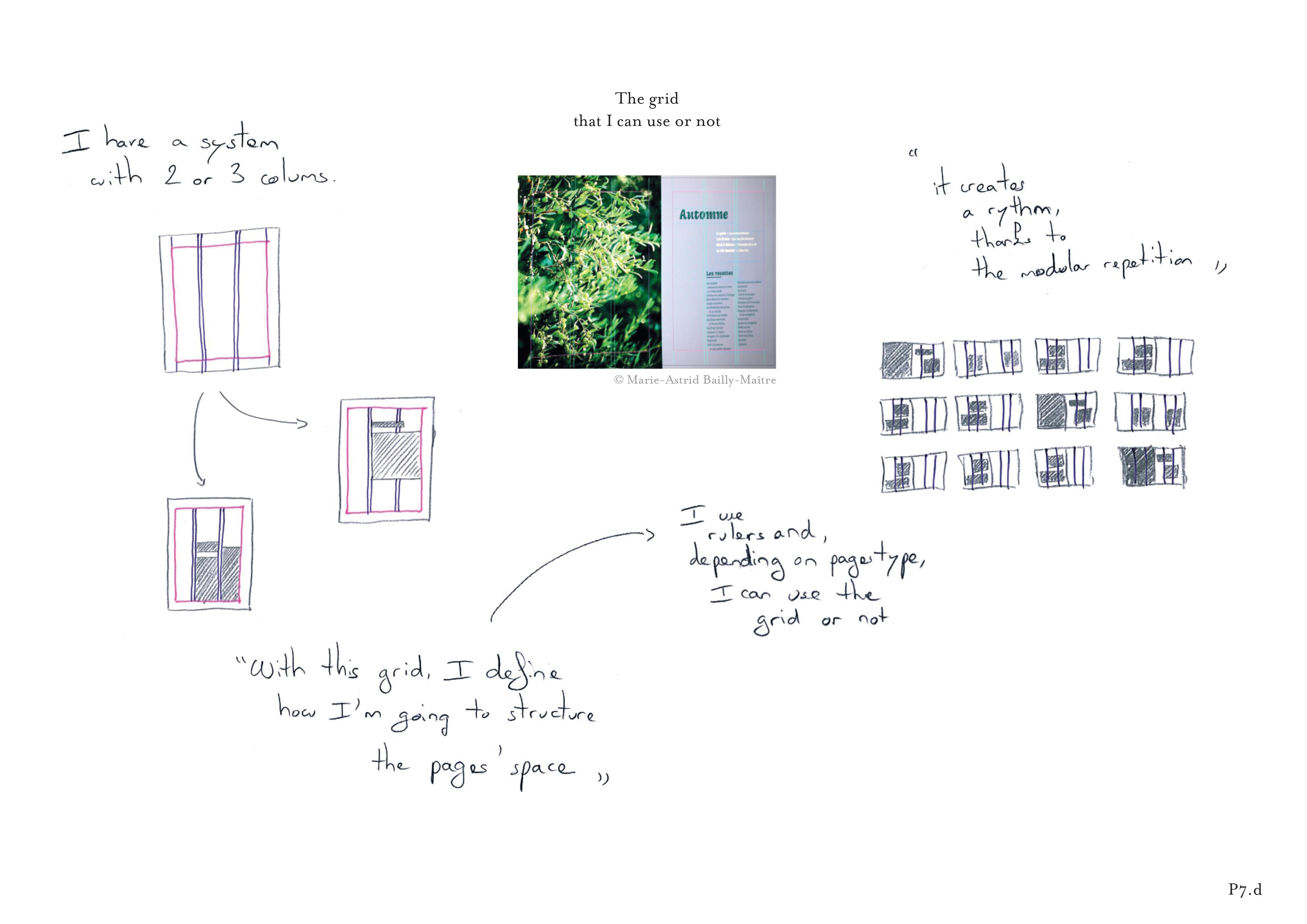

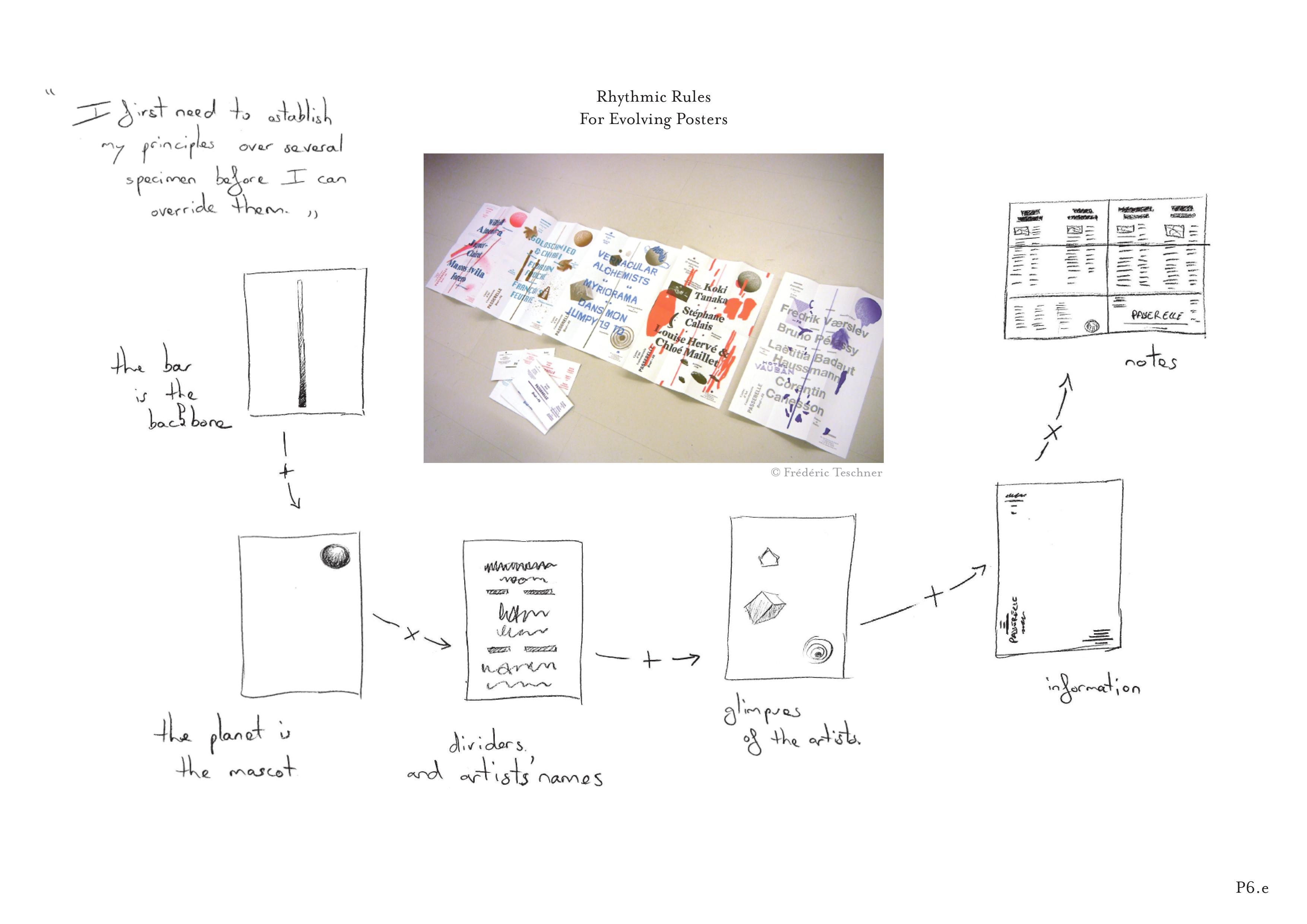

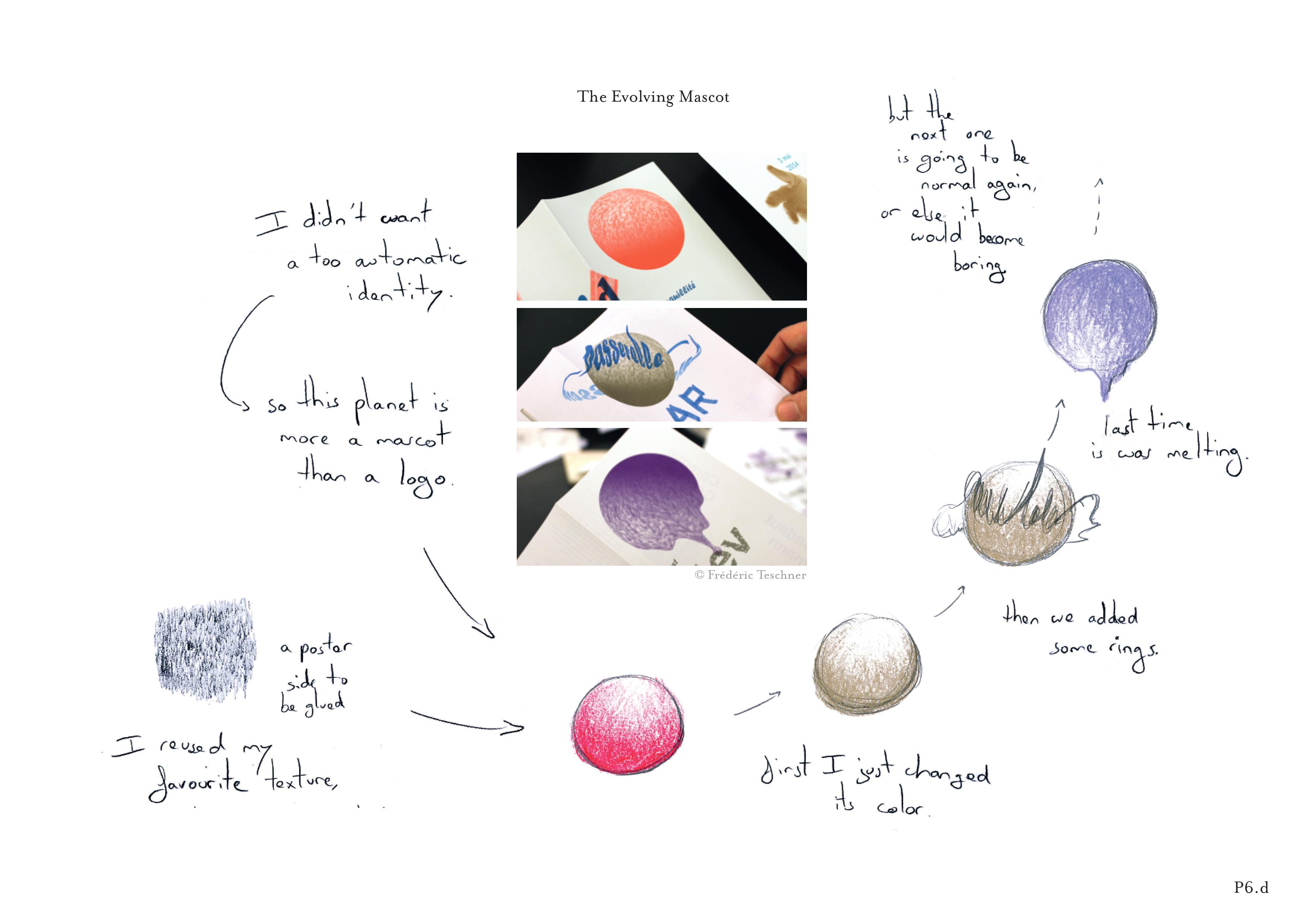

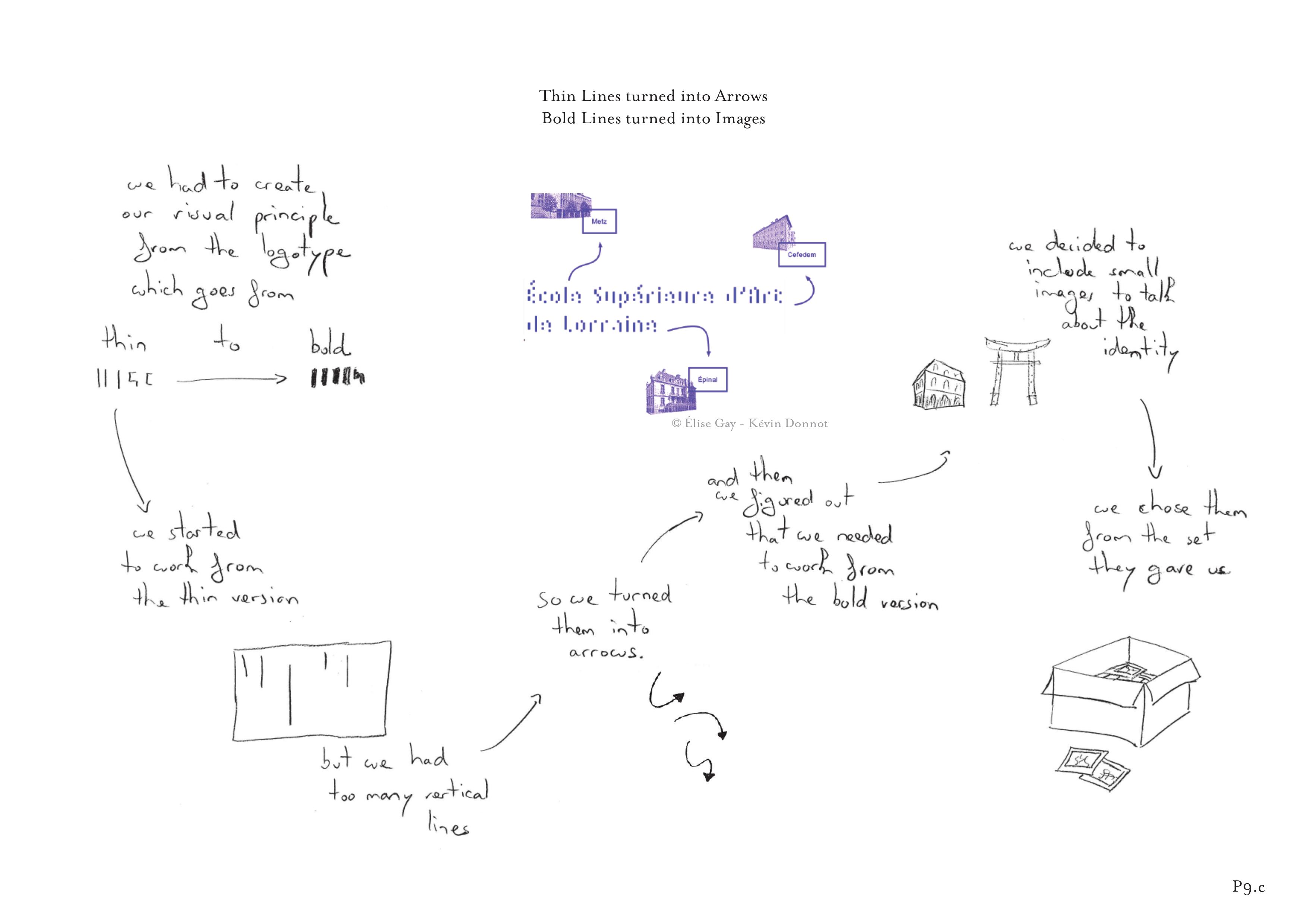

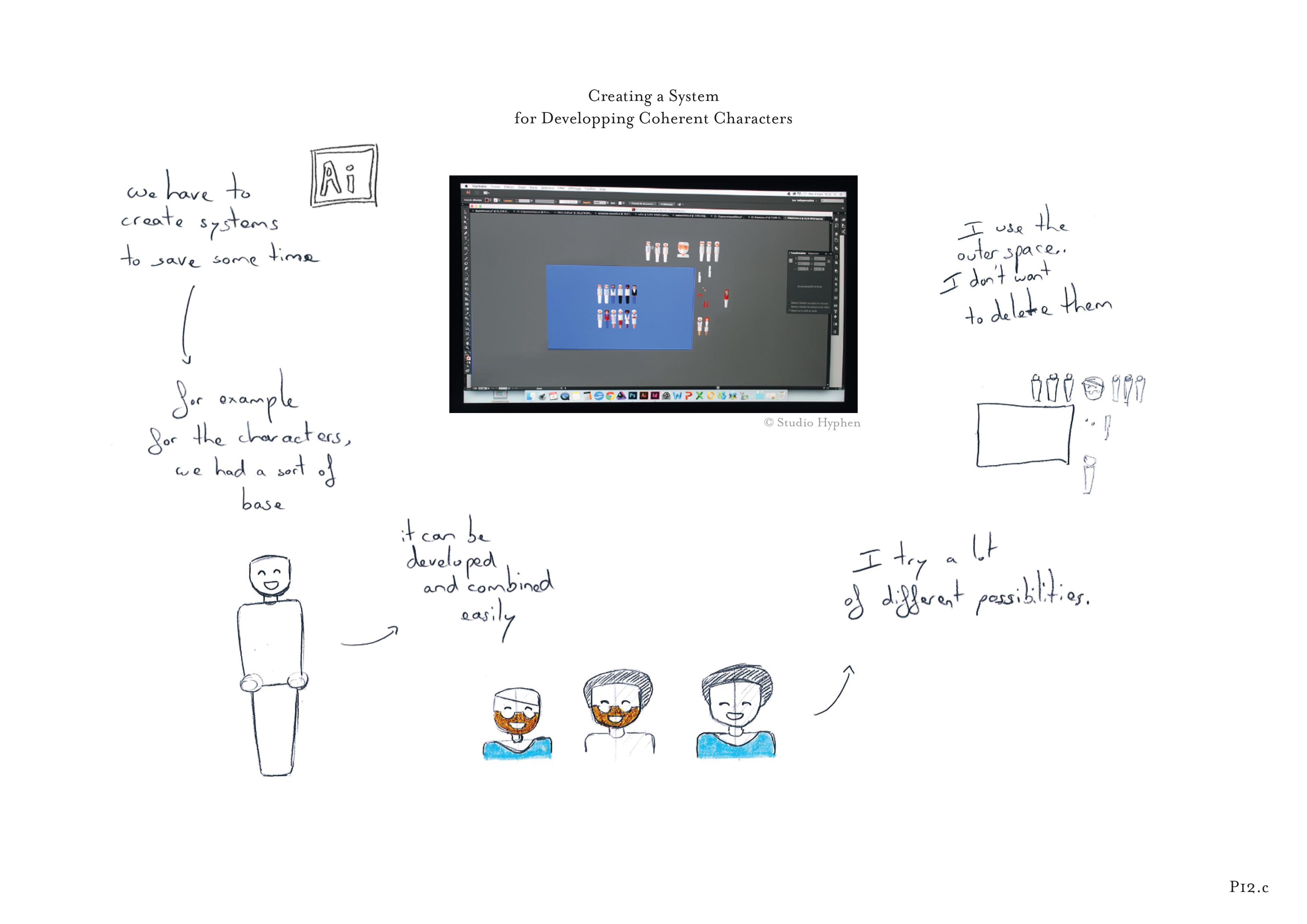

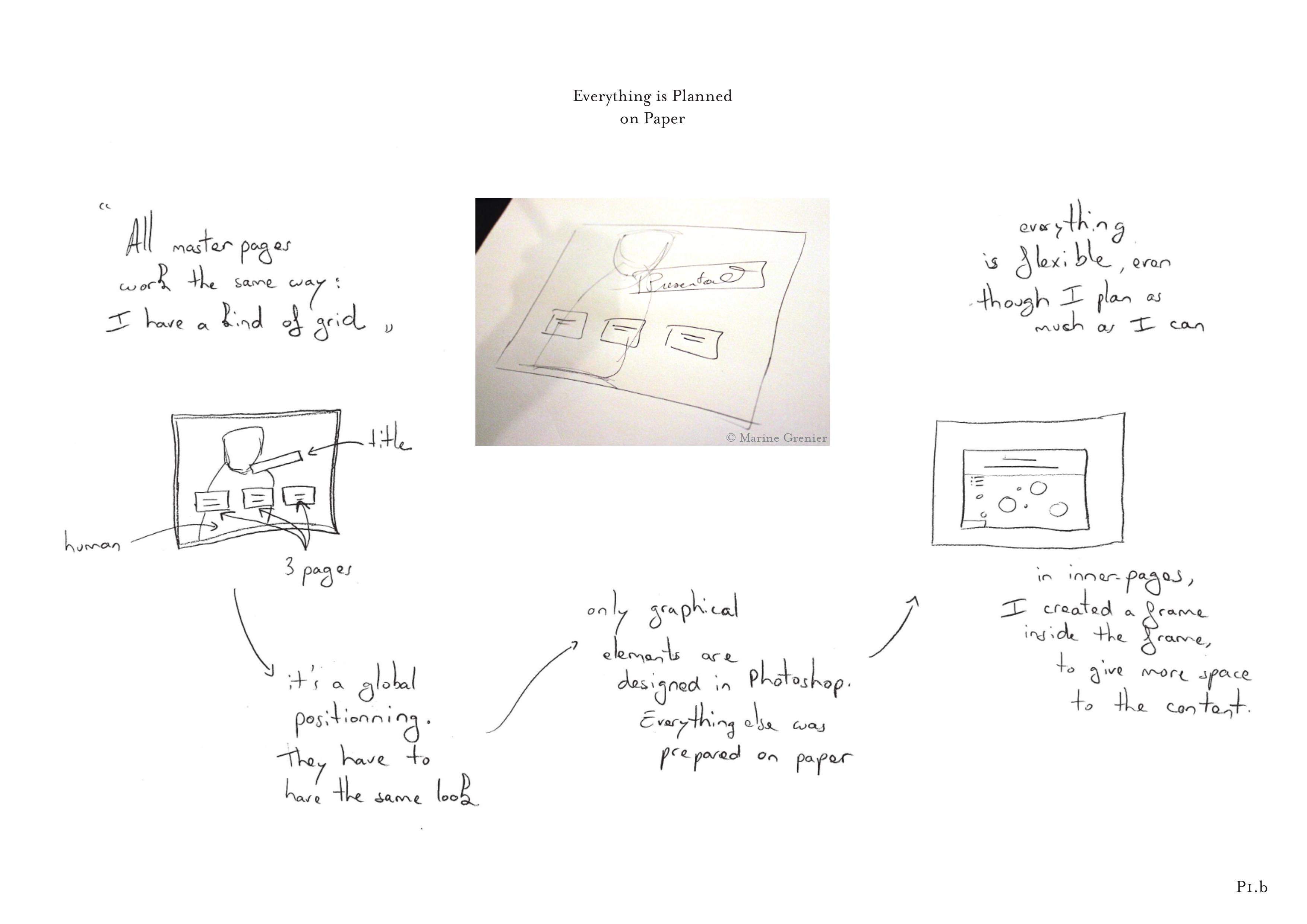

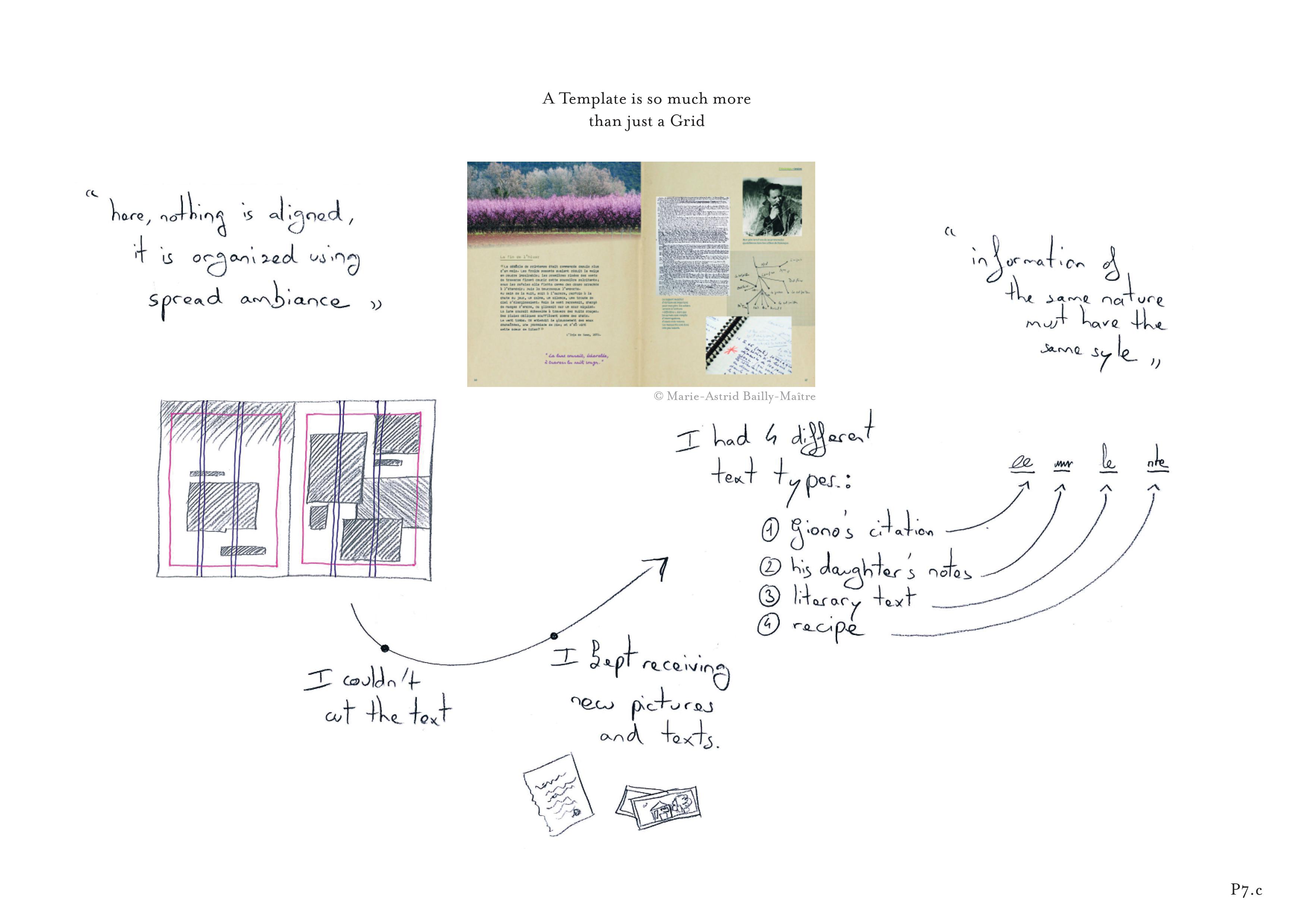

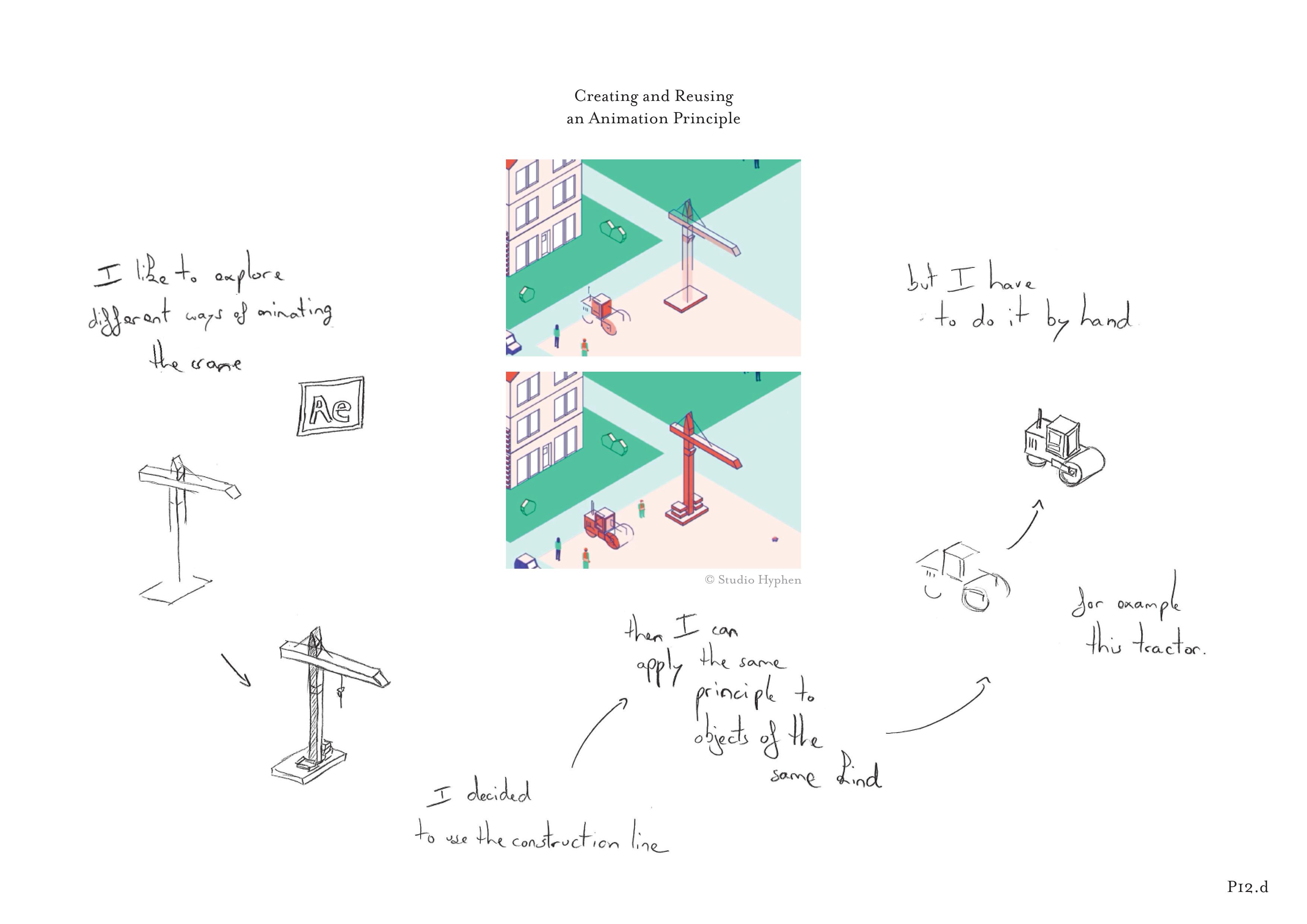

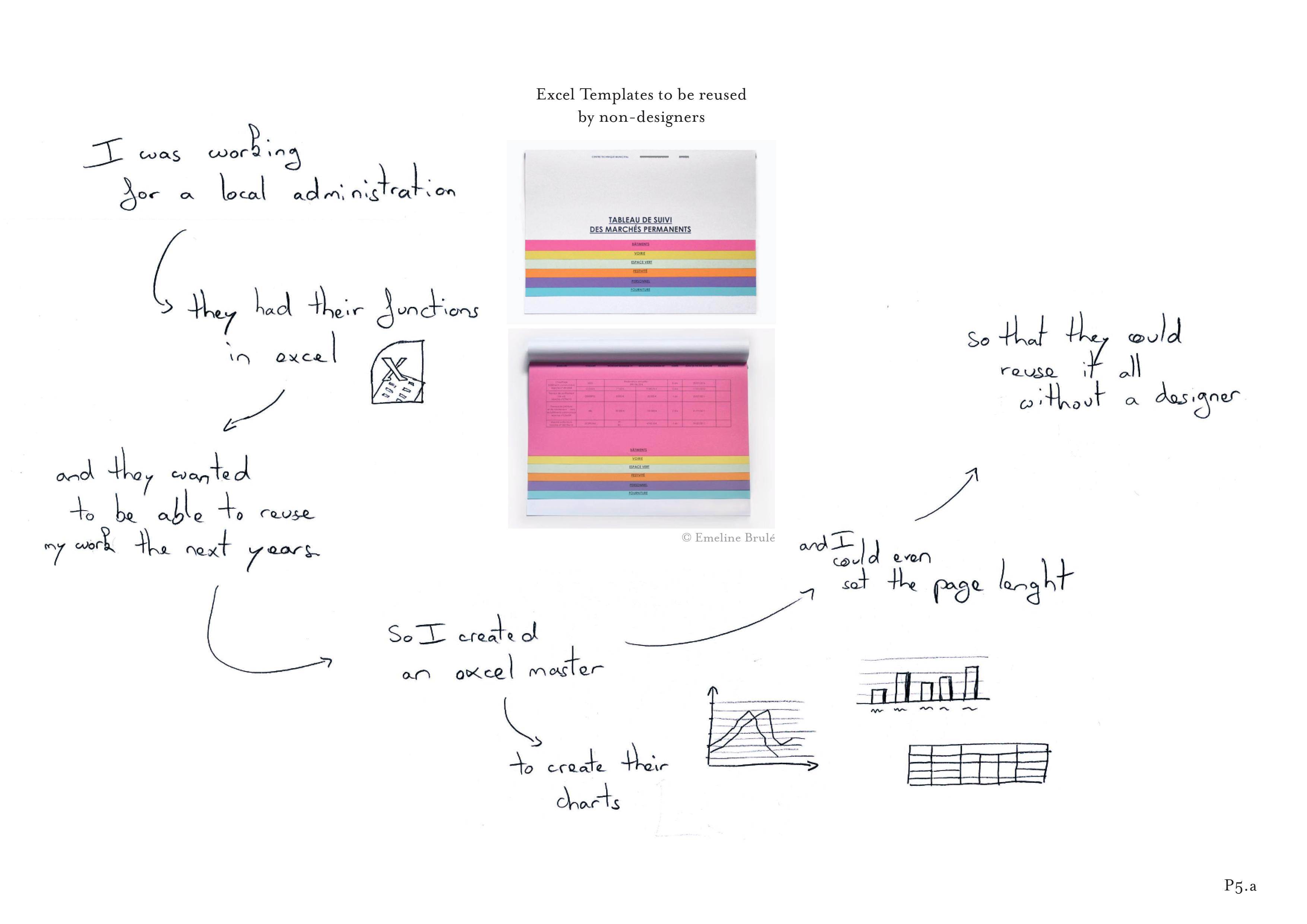

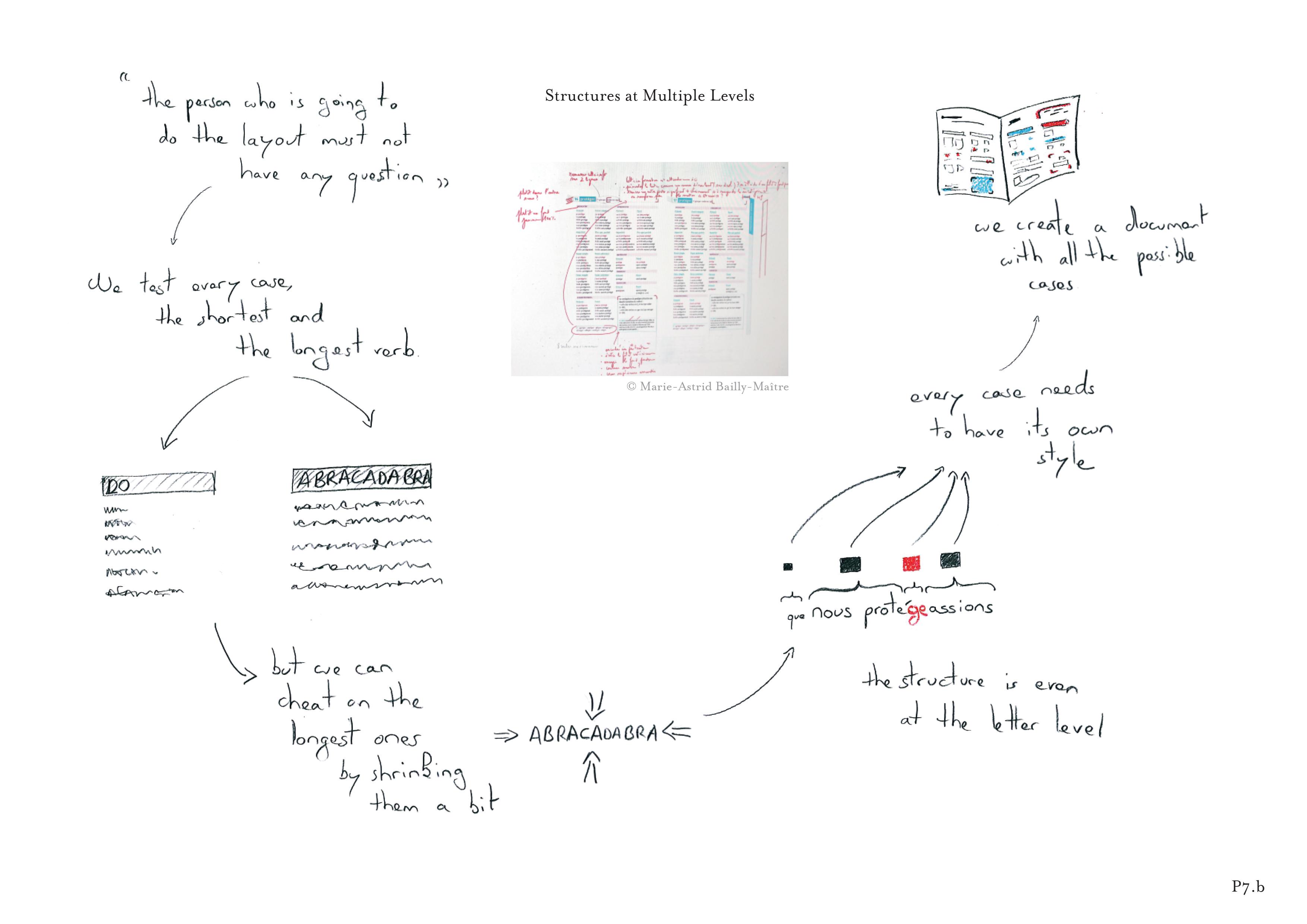

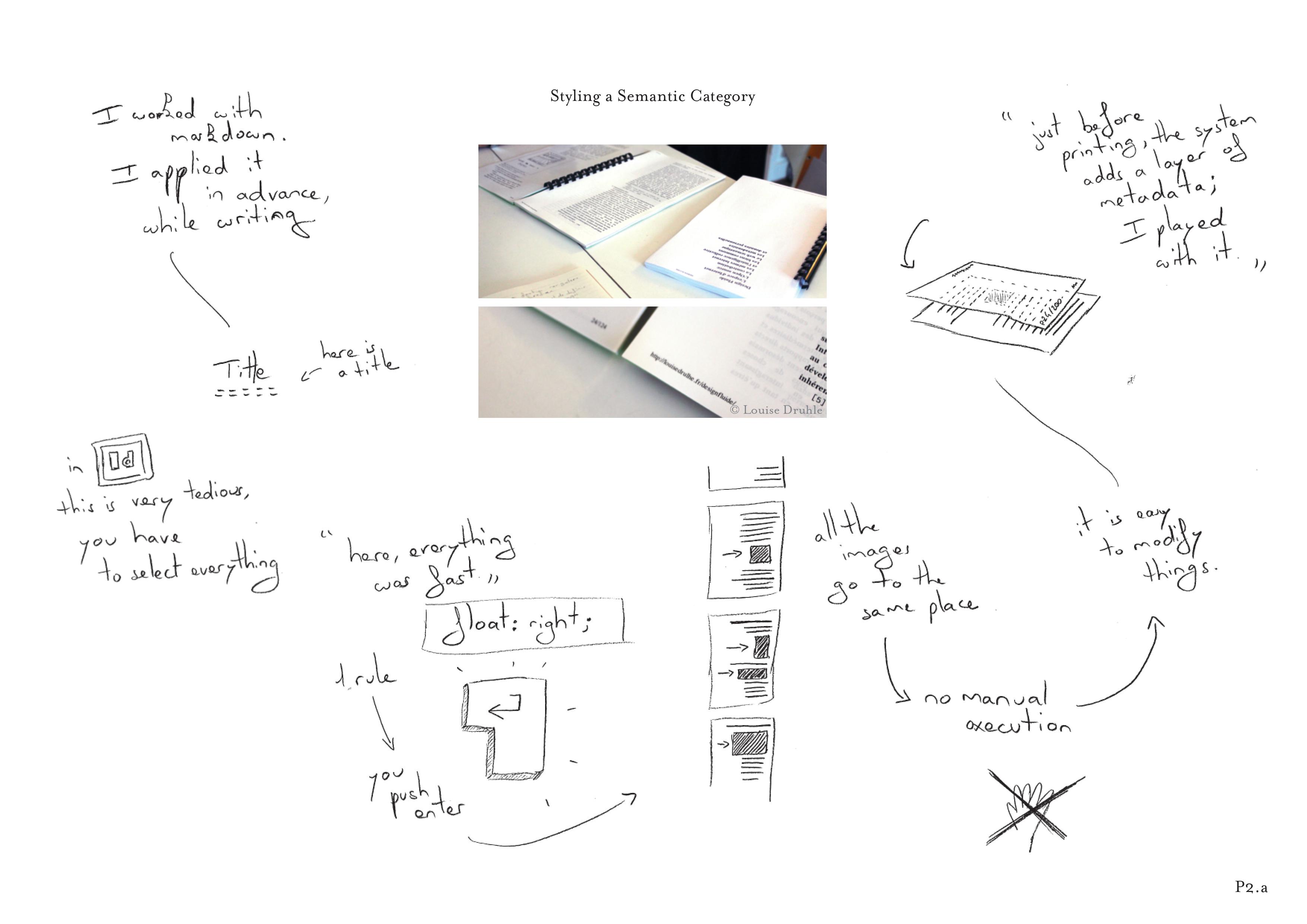

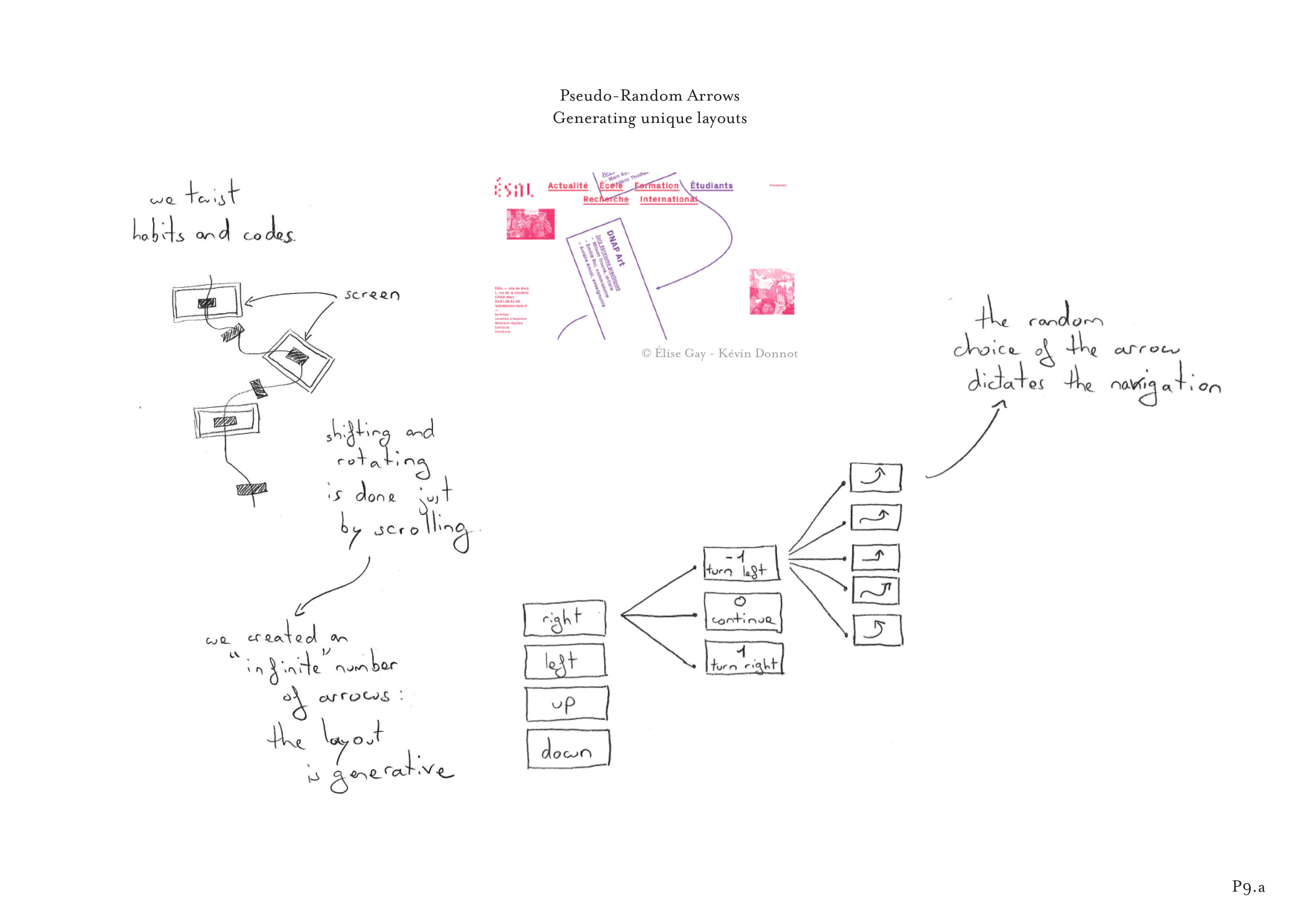

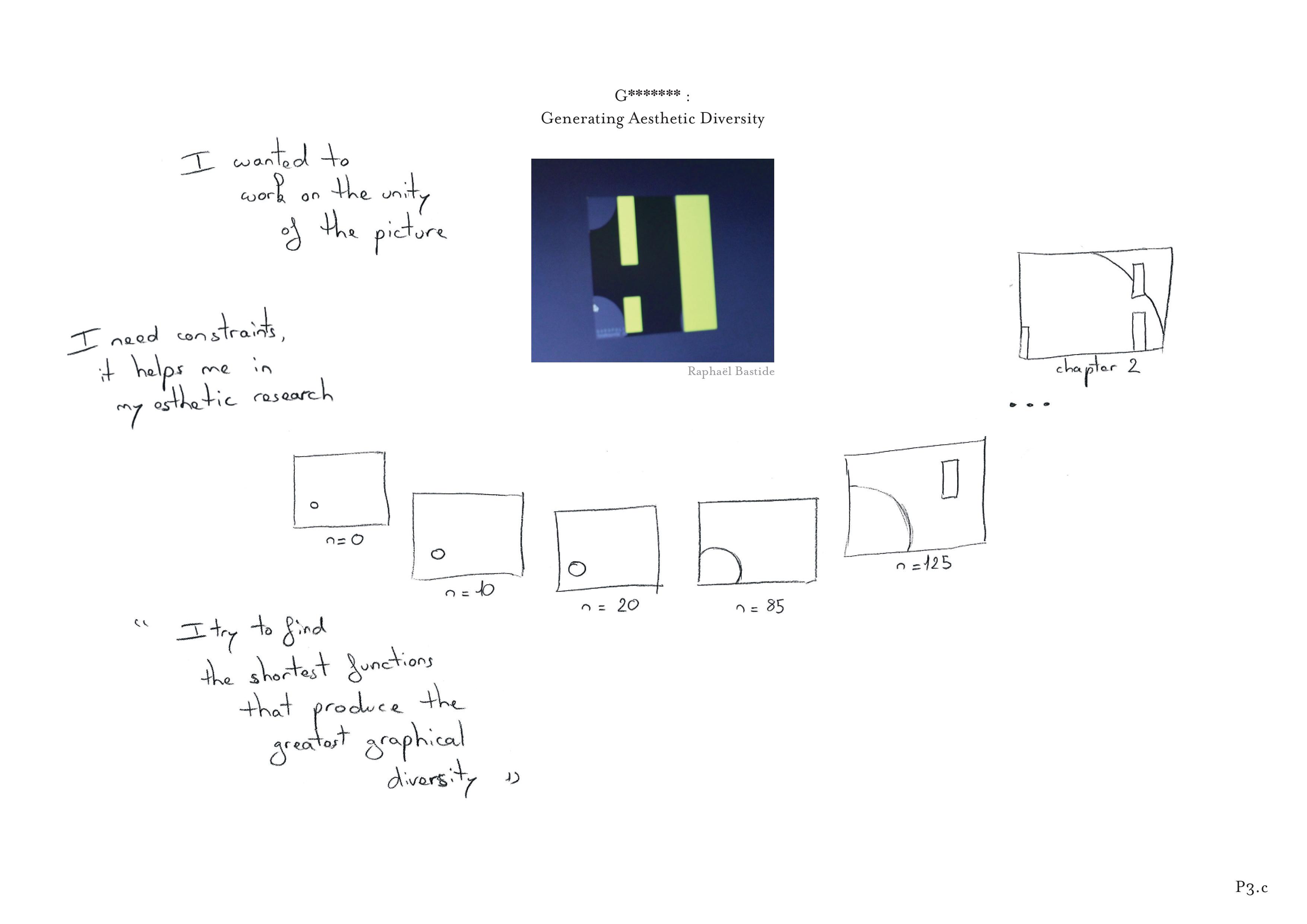

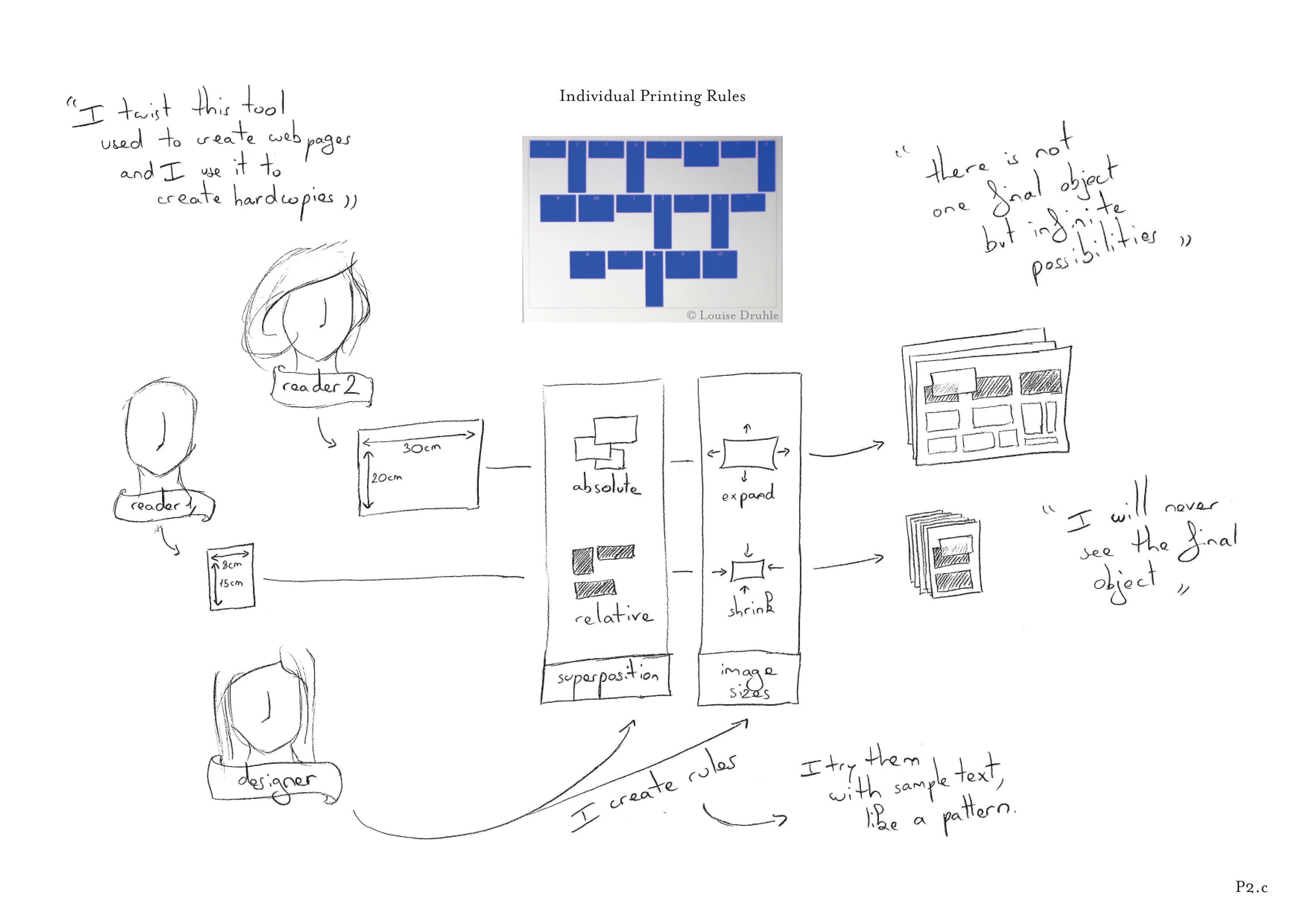

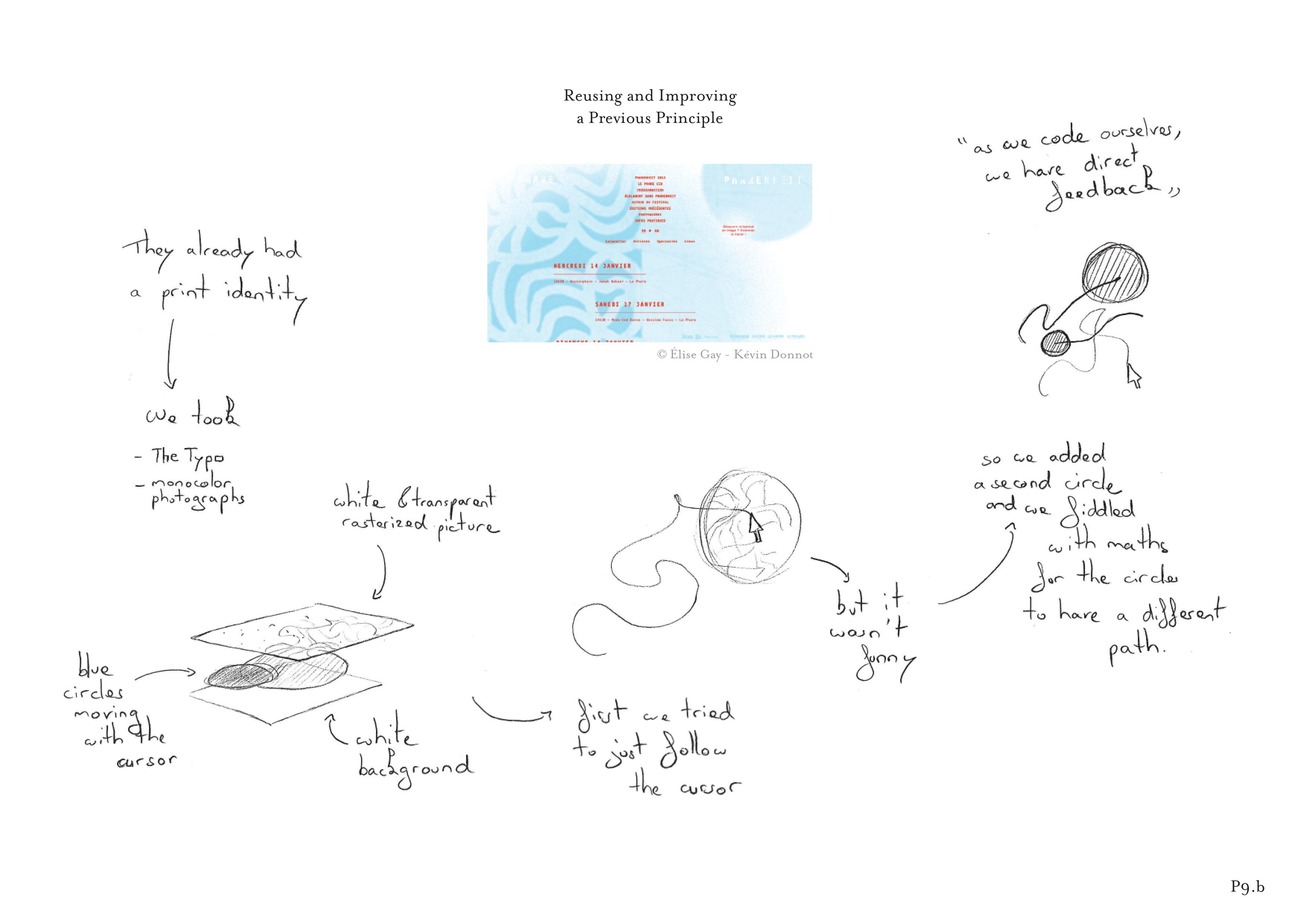

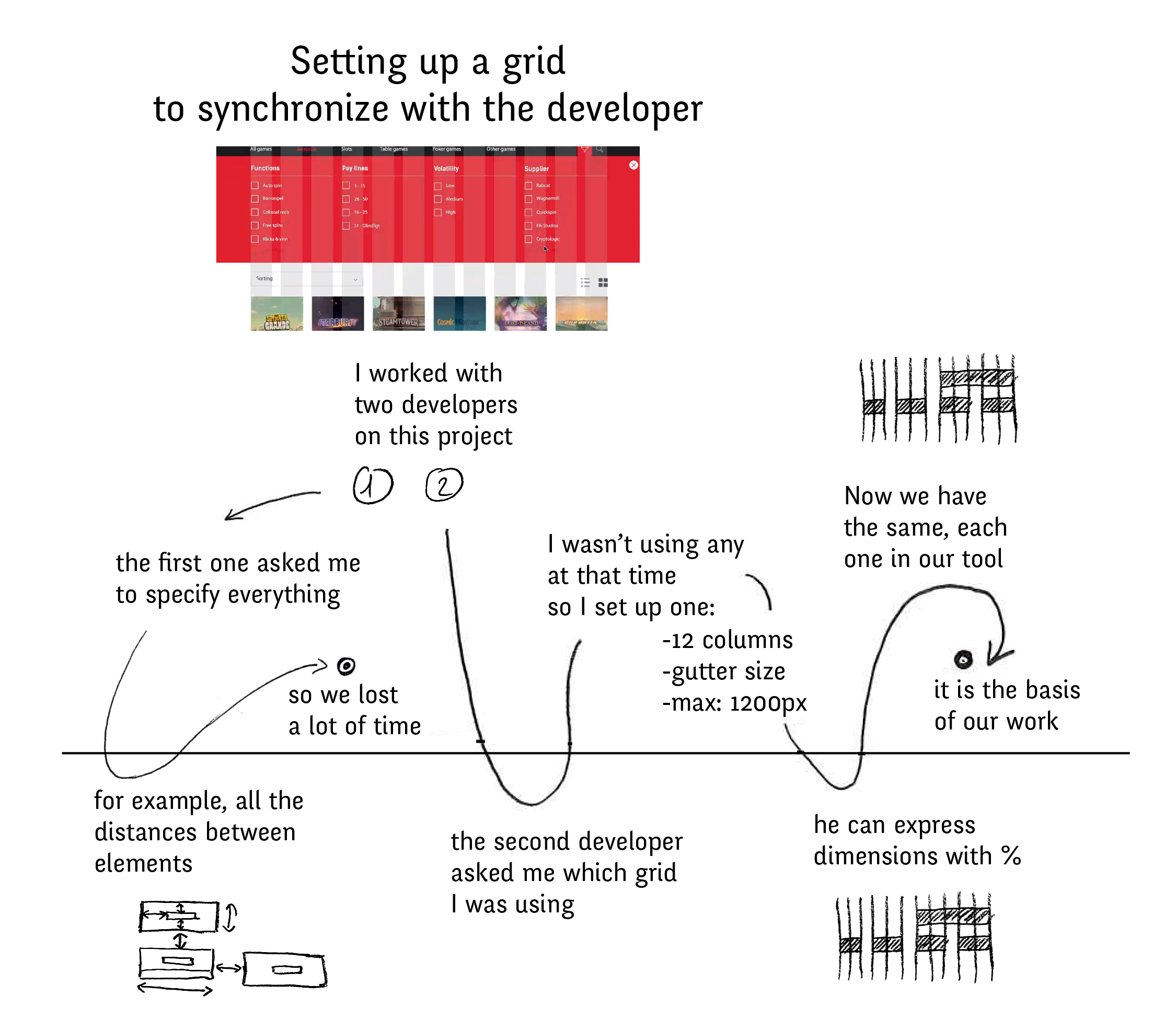

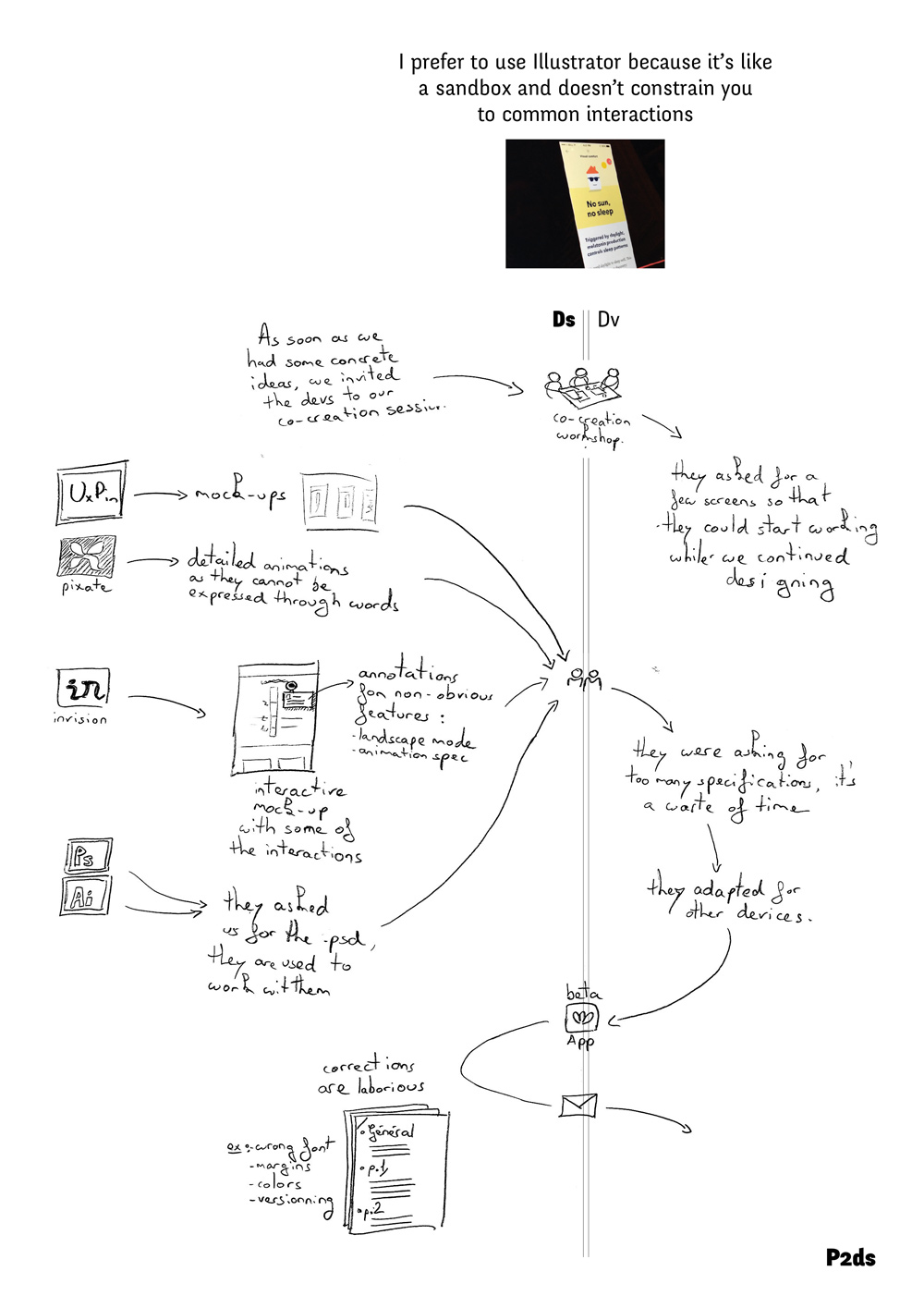

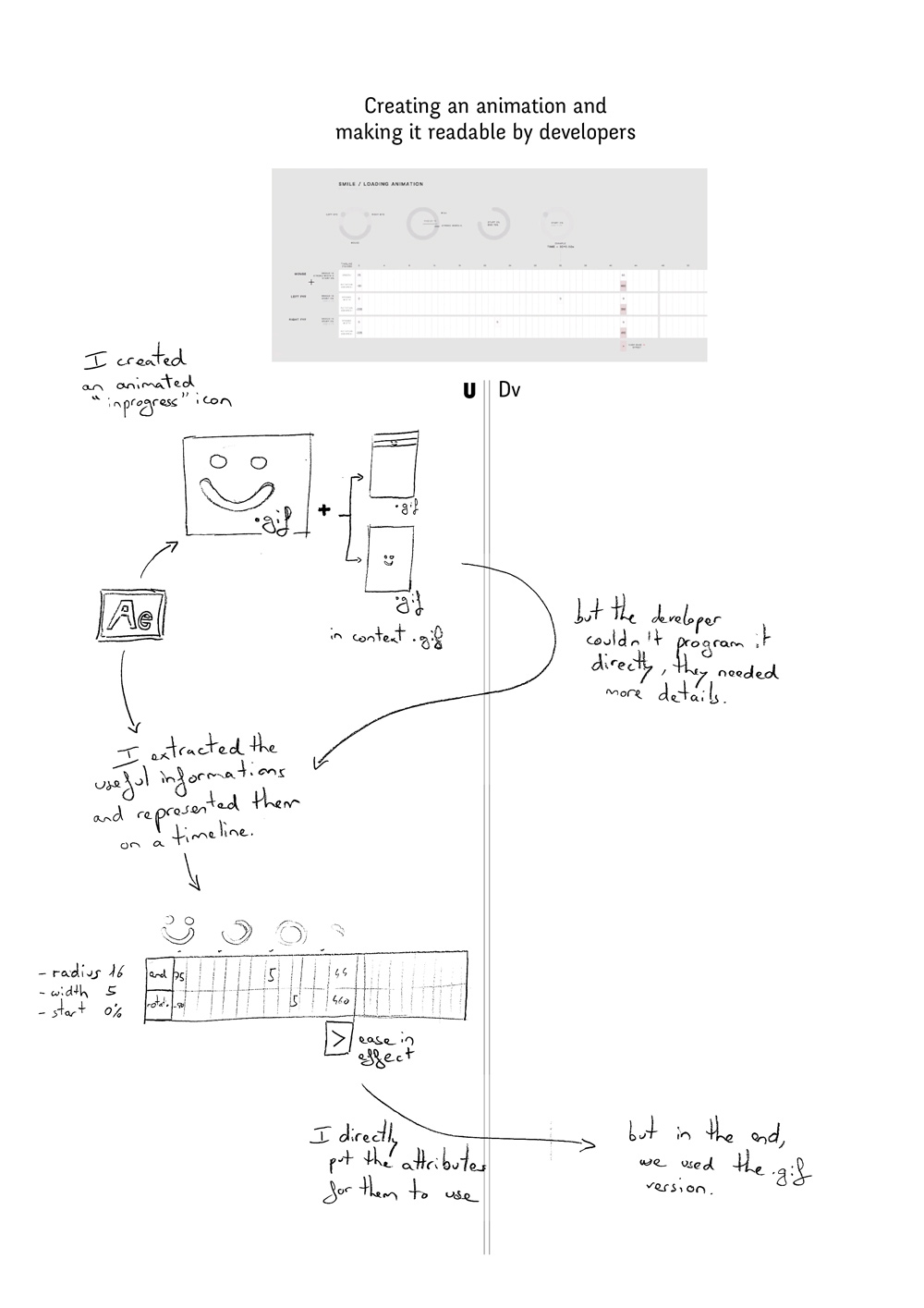

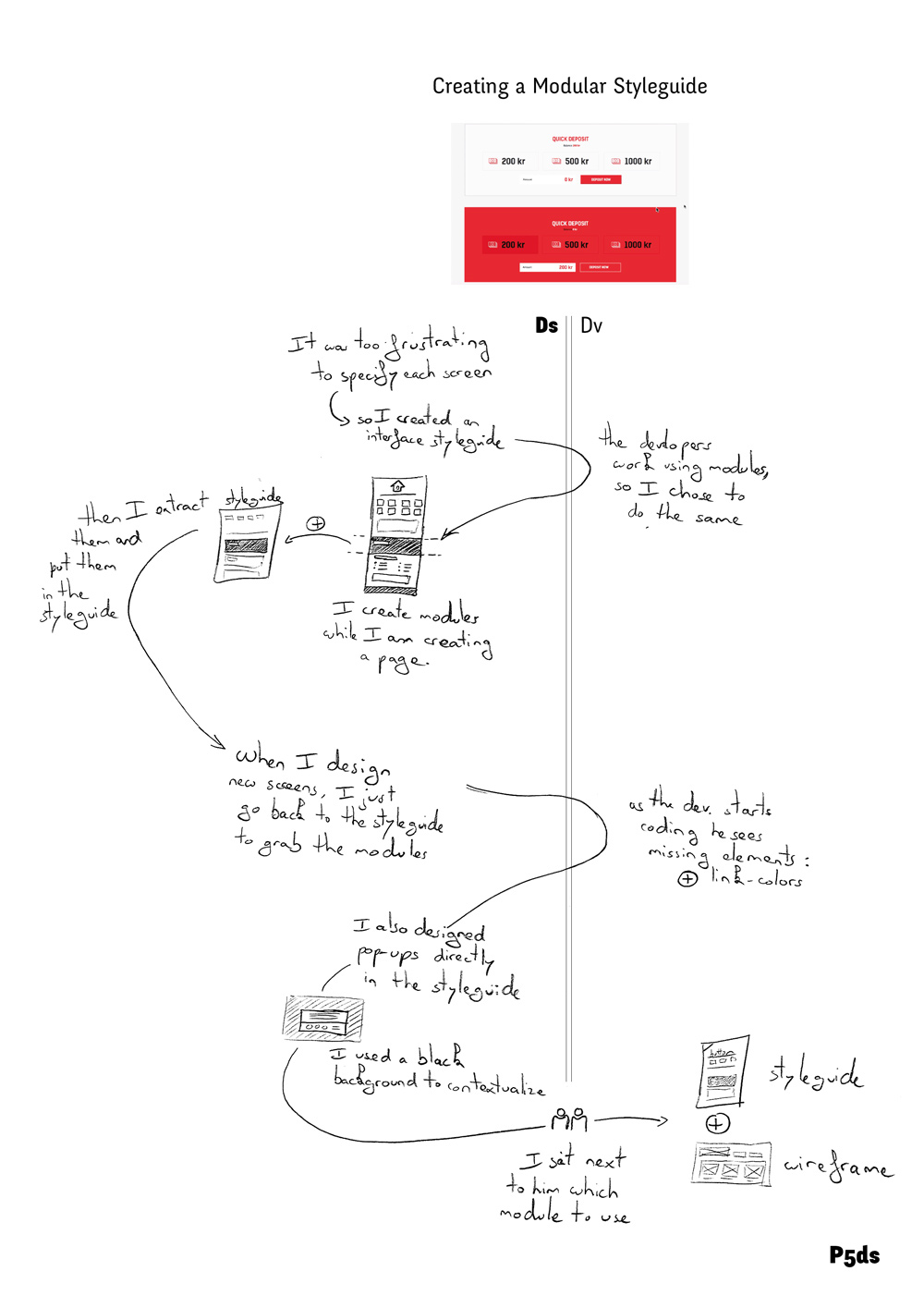

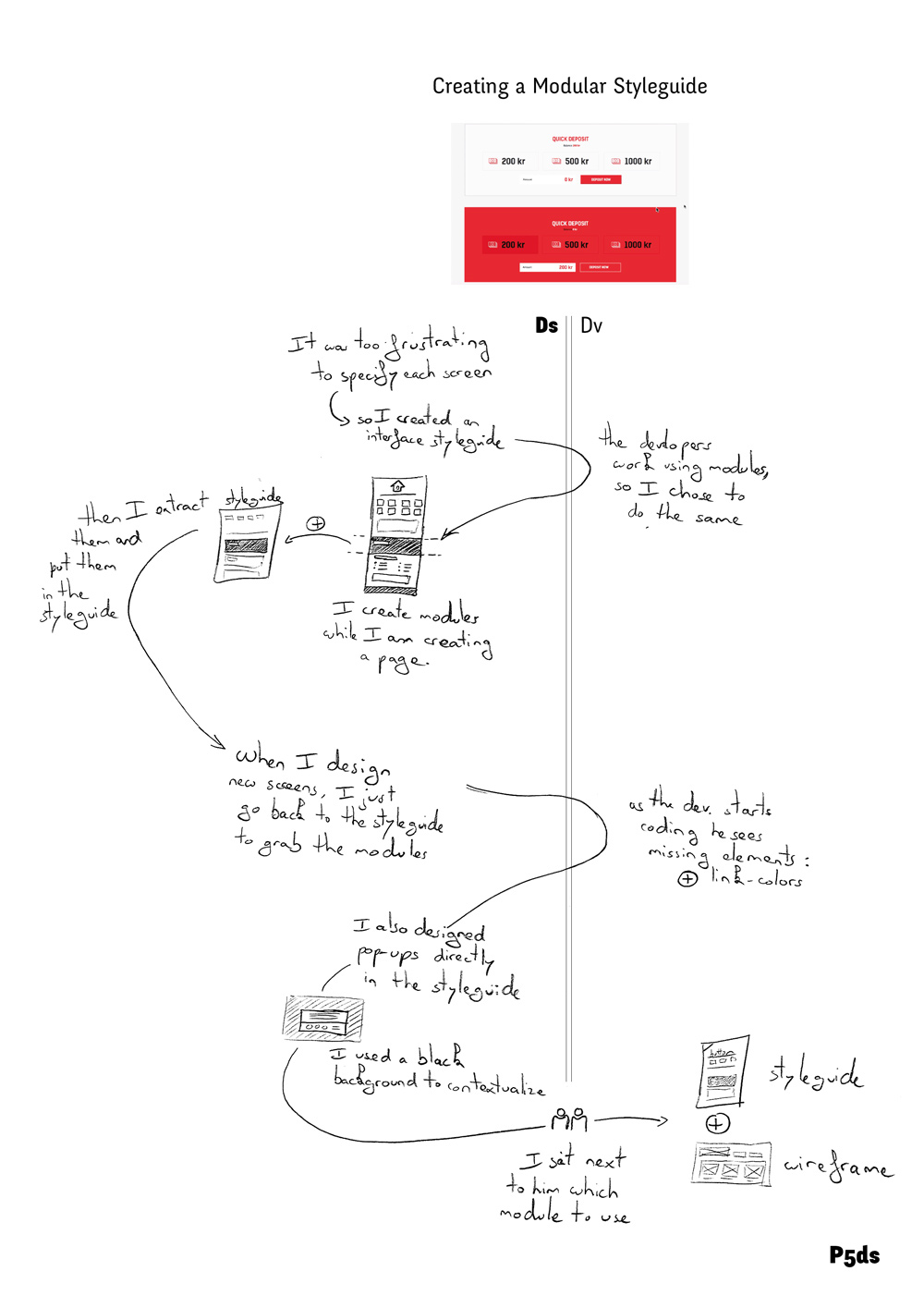

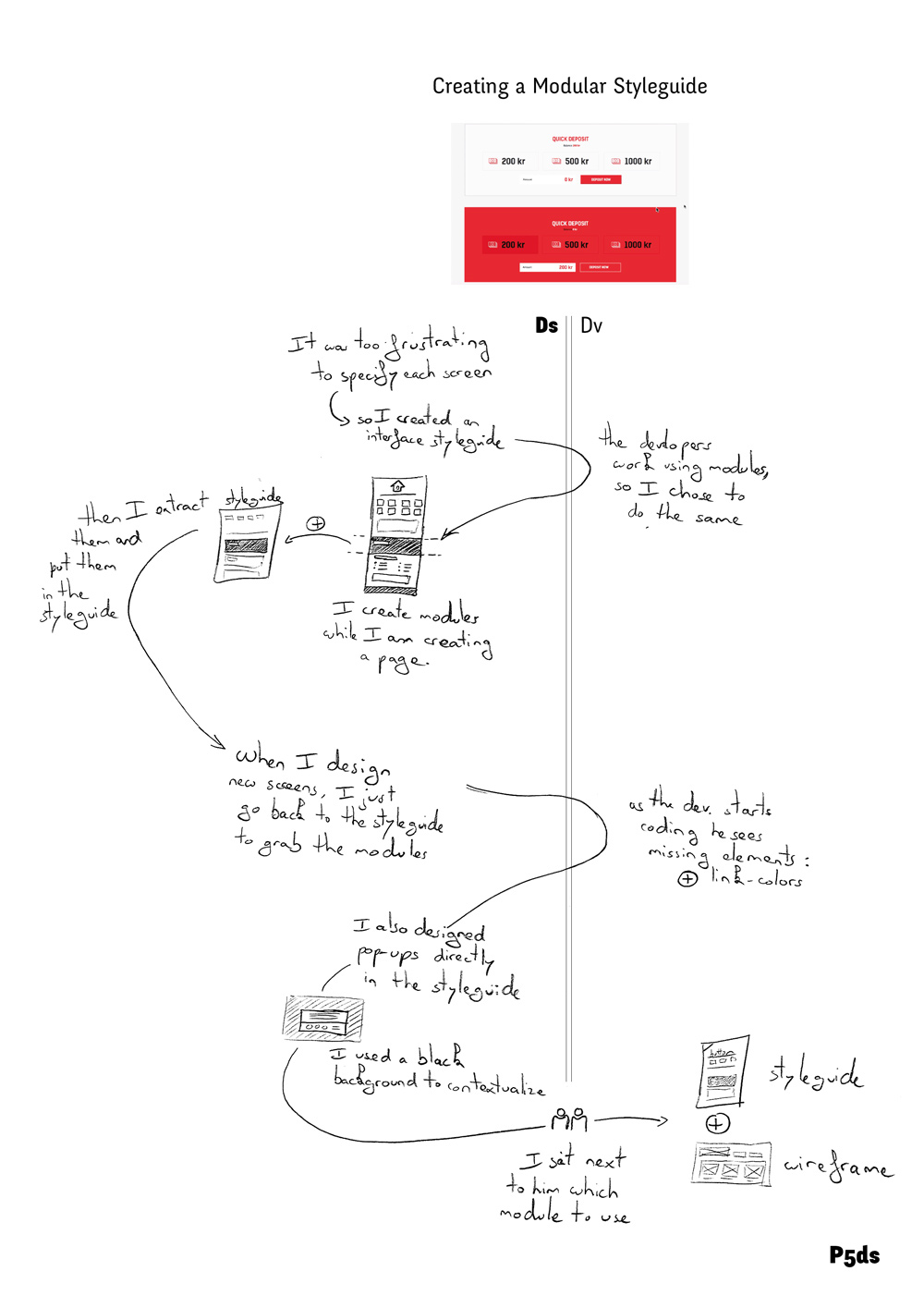

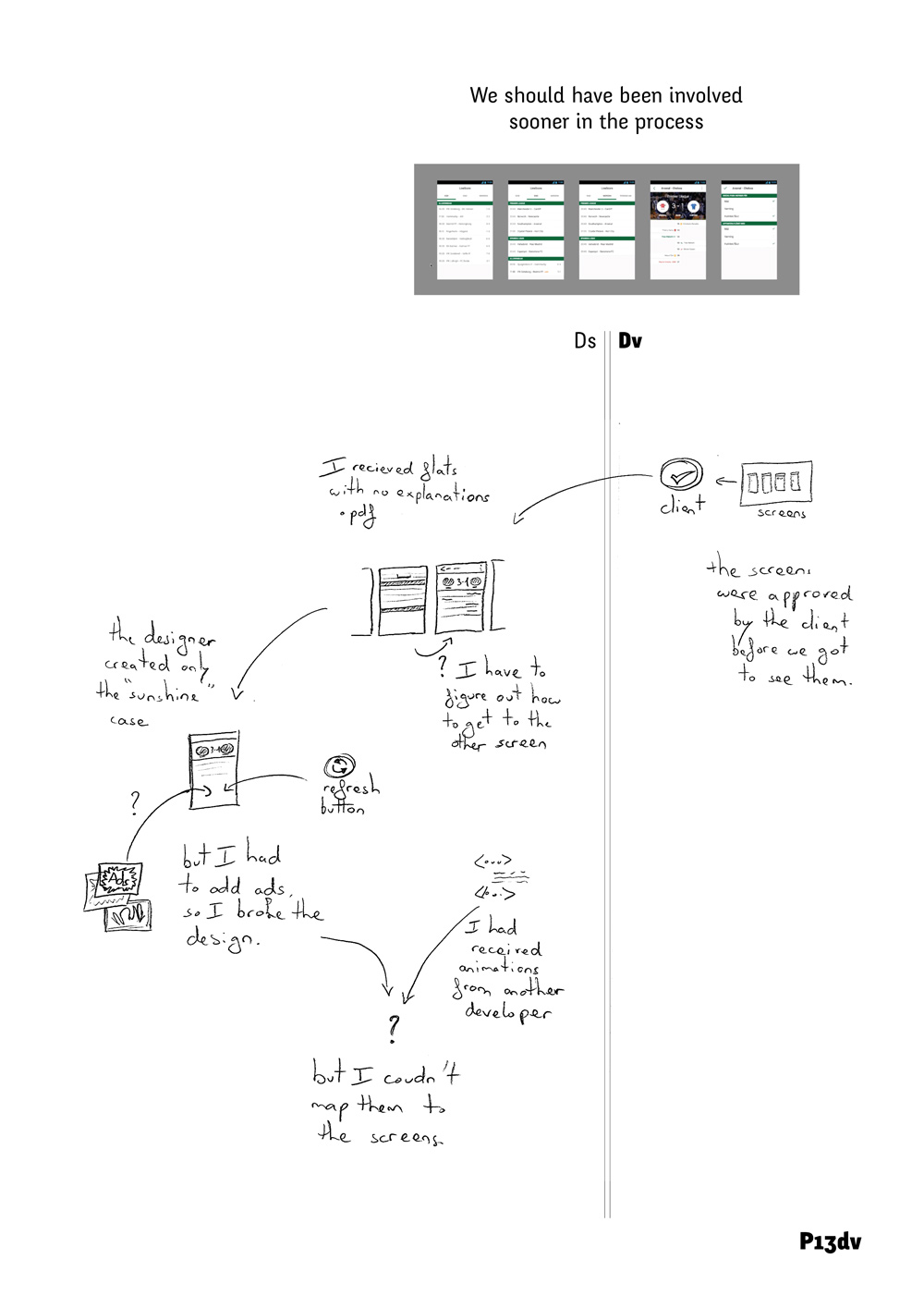

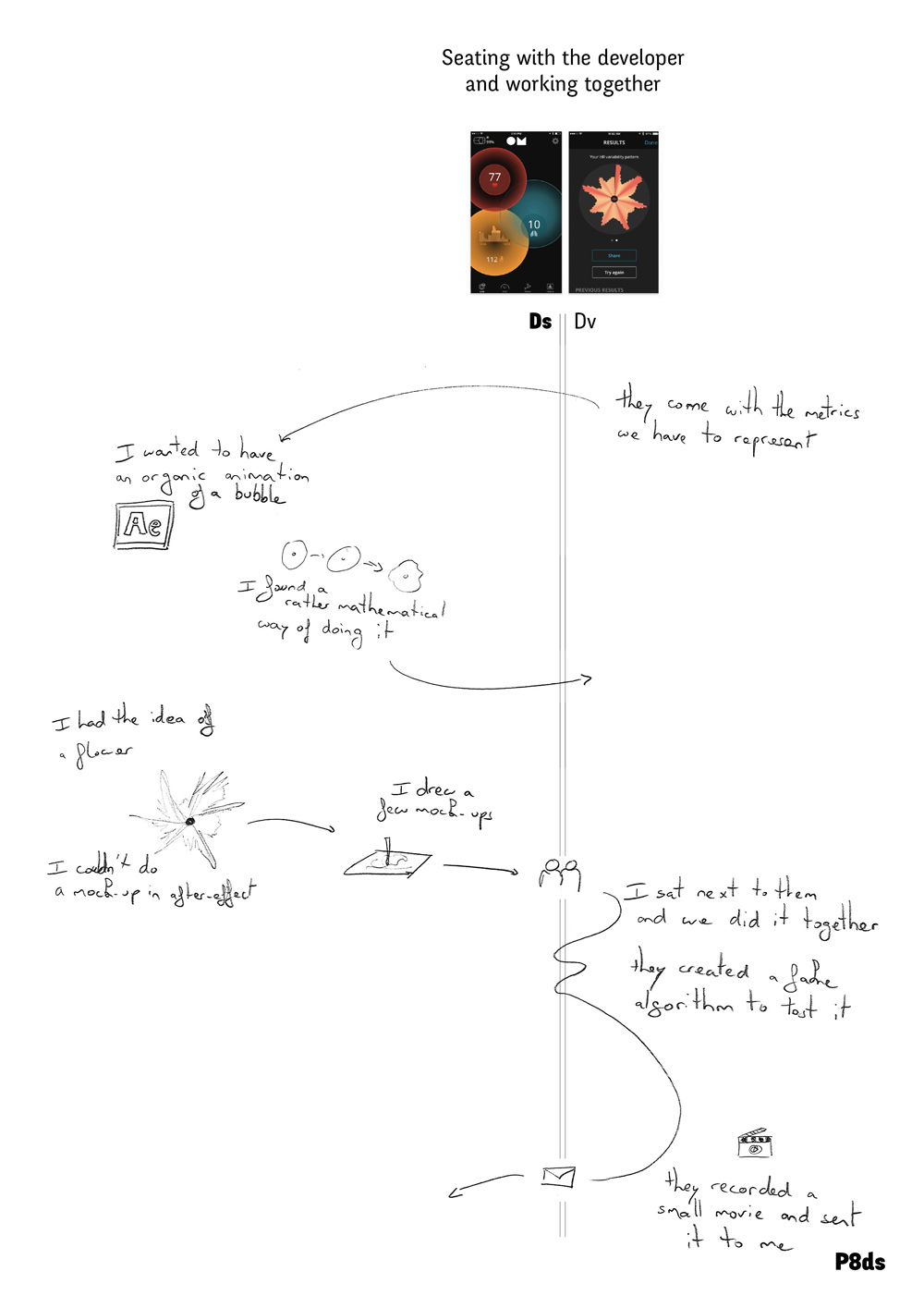

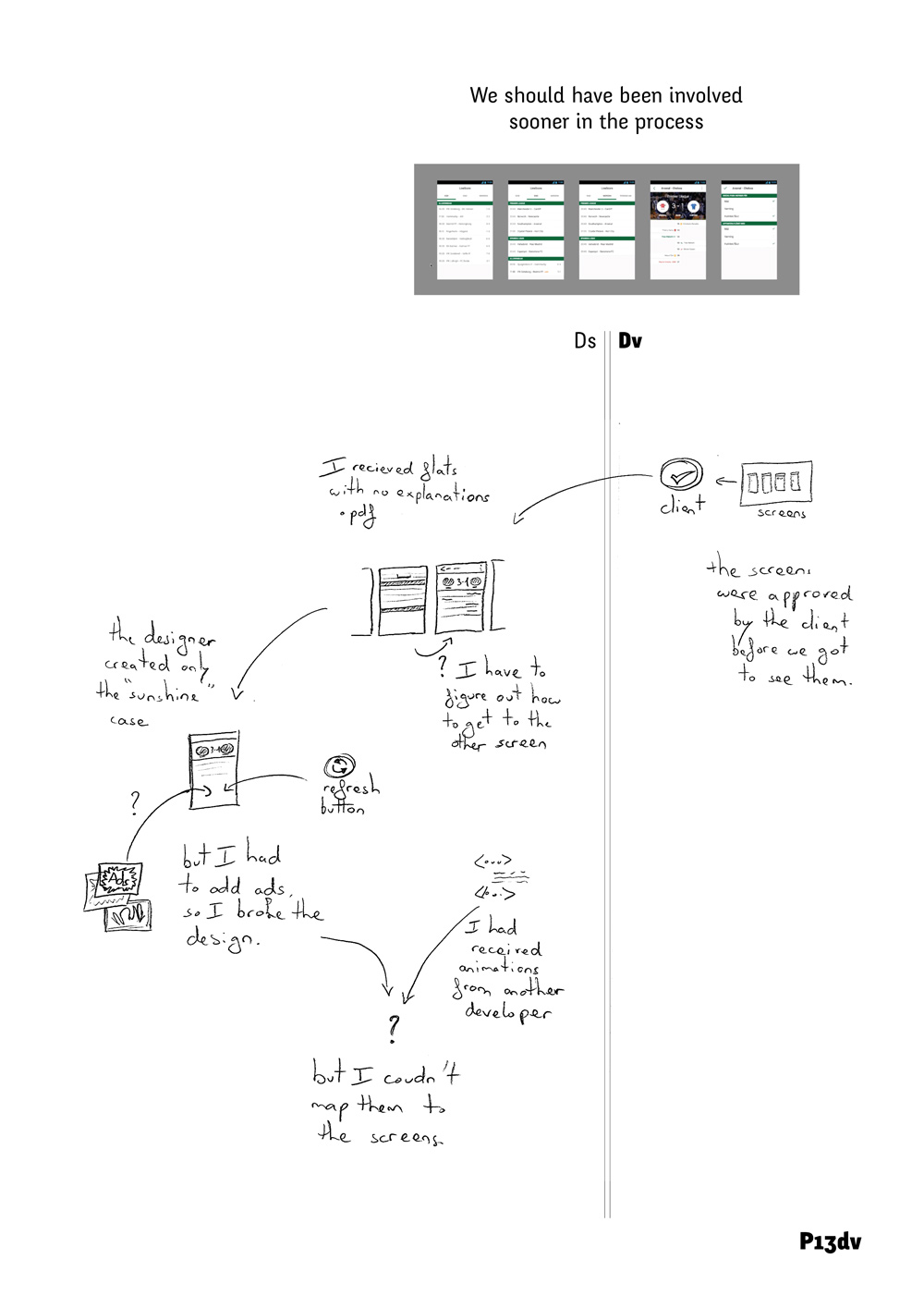

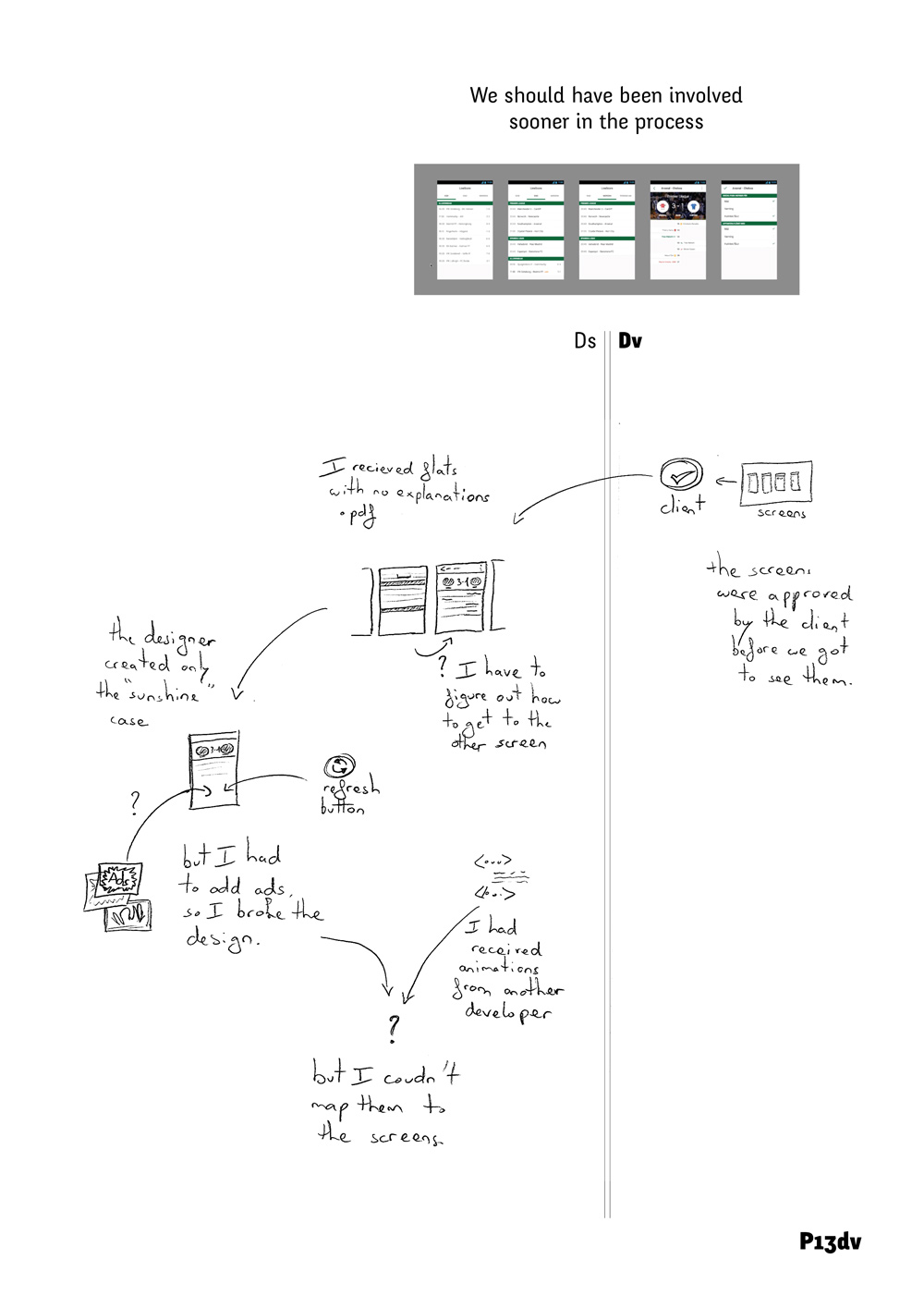

StoryPortraits

In the first part of this thesis, I inquire, document and analyze designers’ practices in order to inform the design of novel digital design tools. Artifacts occupy a central position in designers’ practices and this specificity guided my methodological choices. How can we, as design researchers, best convey the richness of the stories that designers tell about the material aspect of their design processes? In this chapter, I introduce StoryPortraits, a technique for interviewing, synthesizing and visualizing designers’ stories into a form that supports later analysis, and inspires design ideas. I then report on how we used and adapted them for analysis purposes as well as for design conversations.

Context

Interviewing people is one of the main methods used for understanding designers practices and experiences. When we conduct design research, our goal is generally not only to capture and analyze a phenomenon, but also to inspire ideas for products or tools. Wright and McCarthy suggest that user-generated stories (Wright and McCarthy, 2005) can inspire ideas throughout the design process. According to anthropologist Tim Ingold, “the advantage of stories, is that they provide to practitioners the means to say what they know without having to specify it.” p231 (Ingold, 2013). In our case, we are interested in retaining qualitative details from the data in a form that supports both analysis and design. In this context, representing the results of these interviews so as to support both analysis and design remains an open question. Current Human-Computer-Interaction (HCI) practice is largely dominated by written accounts, due mostly to the traditional publication format used in HCI. Trying to enrich this linear format, researchers have introduced several methods for documenting different aspects of interviews, including mind maps (Faste and Lin, 2012), and video summaries (Mackay et al., 2002).

Yet, it is generally when documenting their own design process that HCI and design researchers have developed creative techniques. They have also developed techniques to visualize the design process itself, such as previsualization animations (Wang et al., 2014), comics (Dykes et al., 2016), post-hoc annotated portfolios (Gaver and Bowers, 2012), and design workbooks (Gaver, 2011) that capture design iterations and inspire new design possibilities. However, these methods were created for documenting the design side of projects more than interview results. We lack a concise, visual-based method of capturing current design processes and using them as a foundation for design.

When trained as designers, design researchers use sketching as a fundamental medium of expression, but also as a medium for recording. In his interaction design sketchbook, Verplank (Verplank, 2009) describes sketching as an essential designer’s tool for capturing preliminary observations and ideas. As McKim explains, seeing, drawing and imagining are tightly linked: “Seeing feeds drawing, drawing improves seeing. What we see is influenced by what we imagine; what we imagine depends on what we see”. Following this path, we introduce StoryPortraits, which capture the situated nature of story-based data through sketches.

Critical Object Interviews

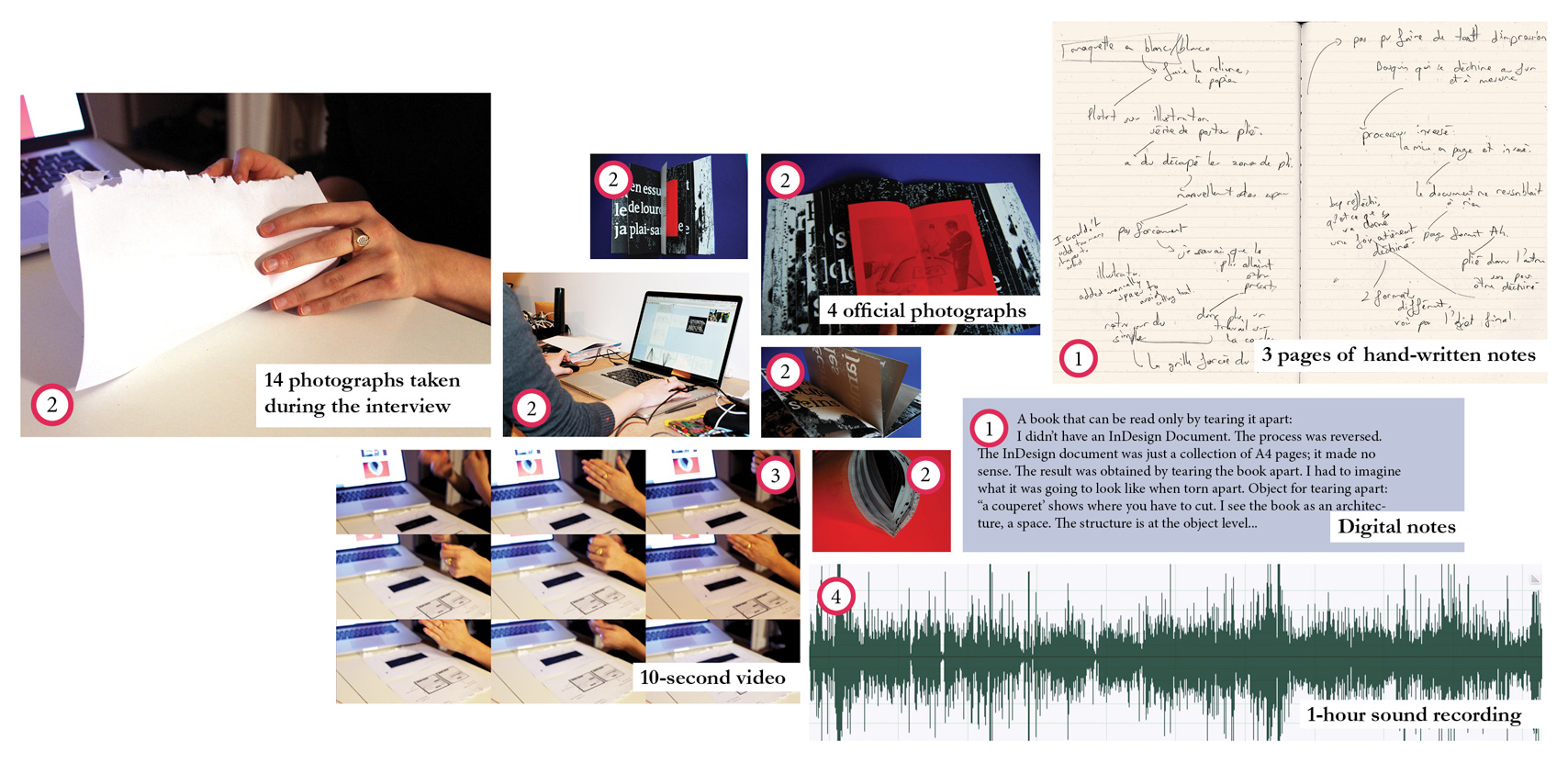

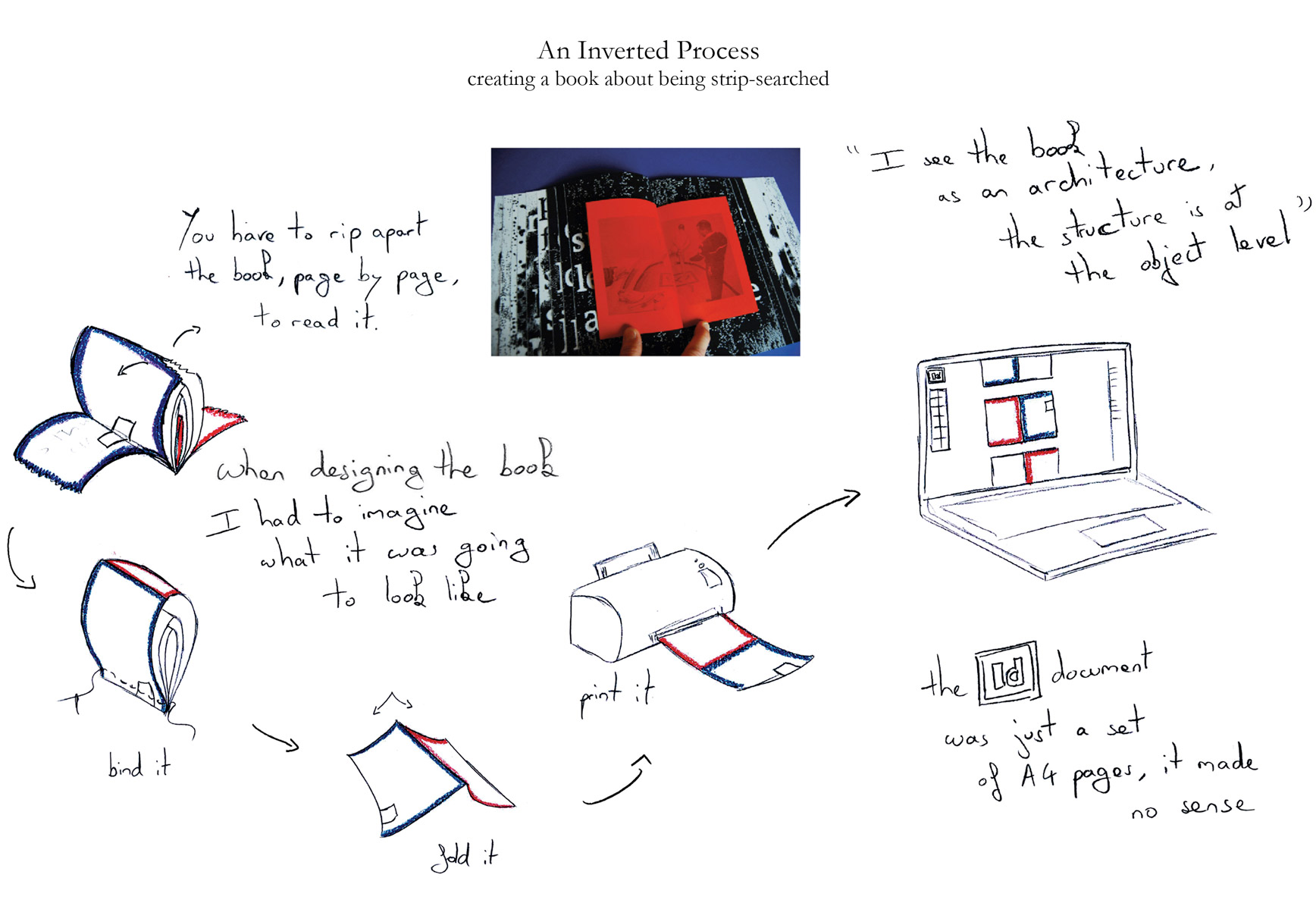

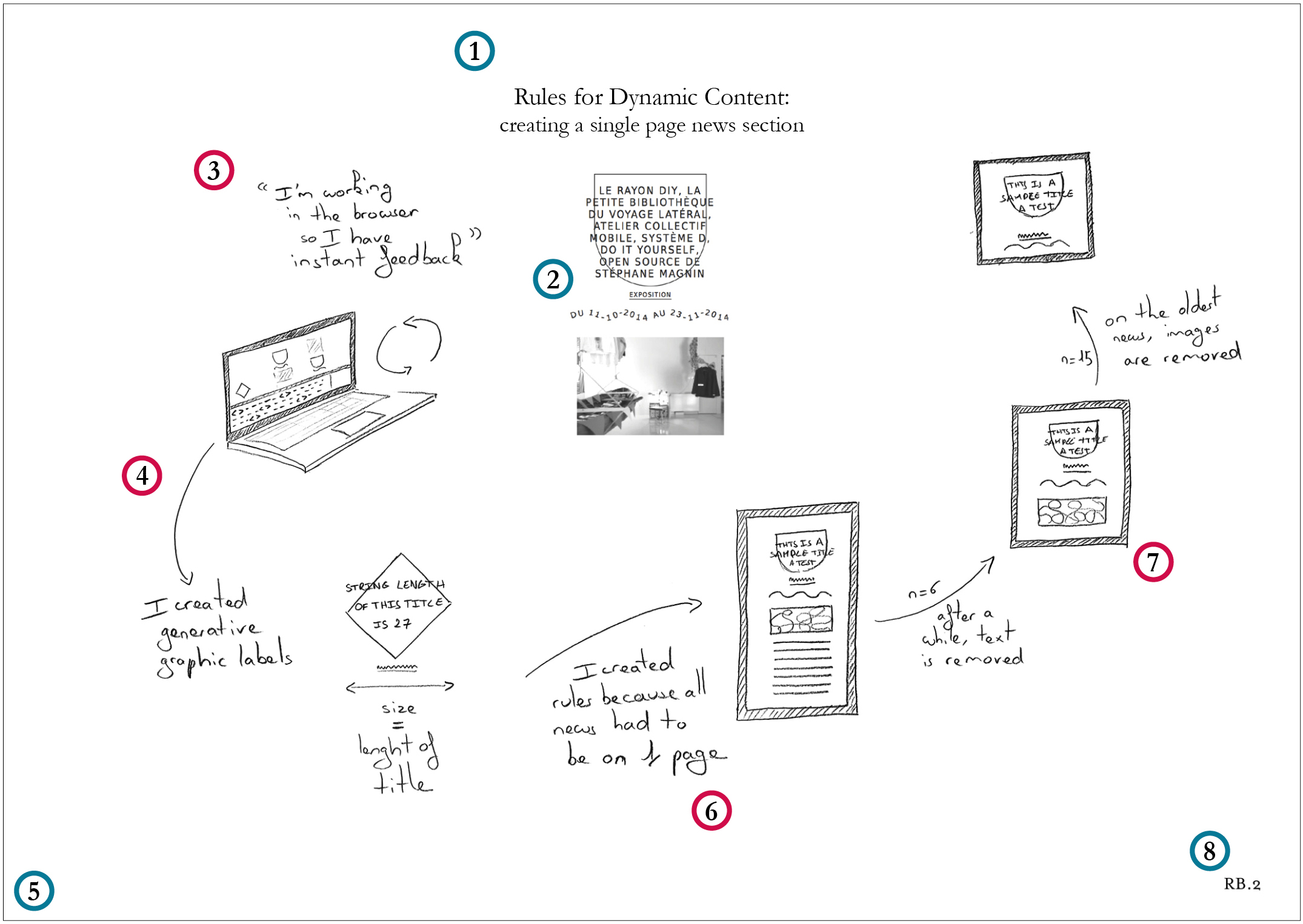

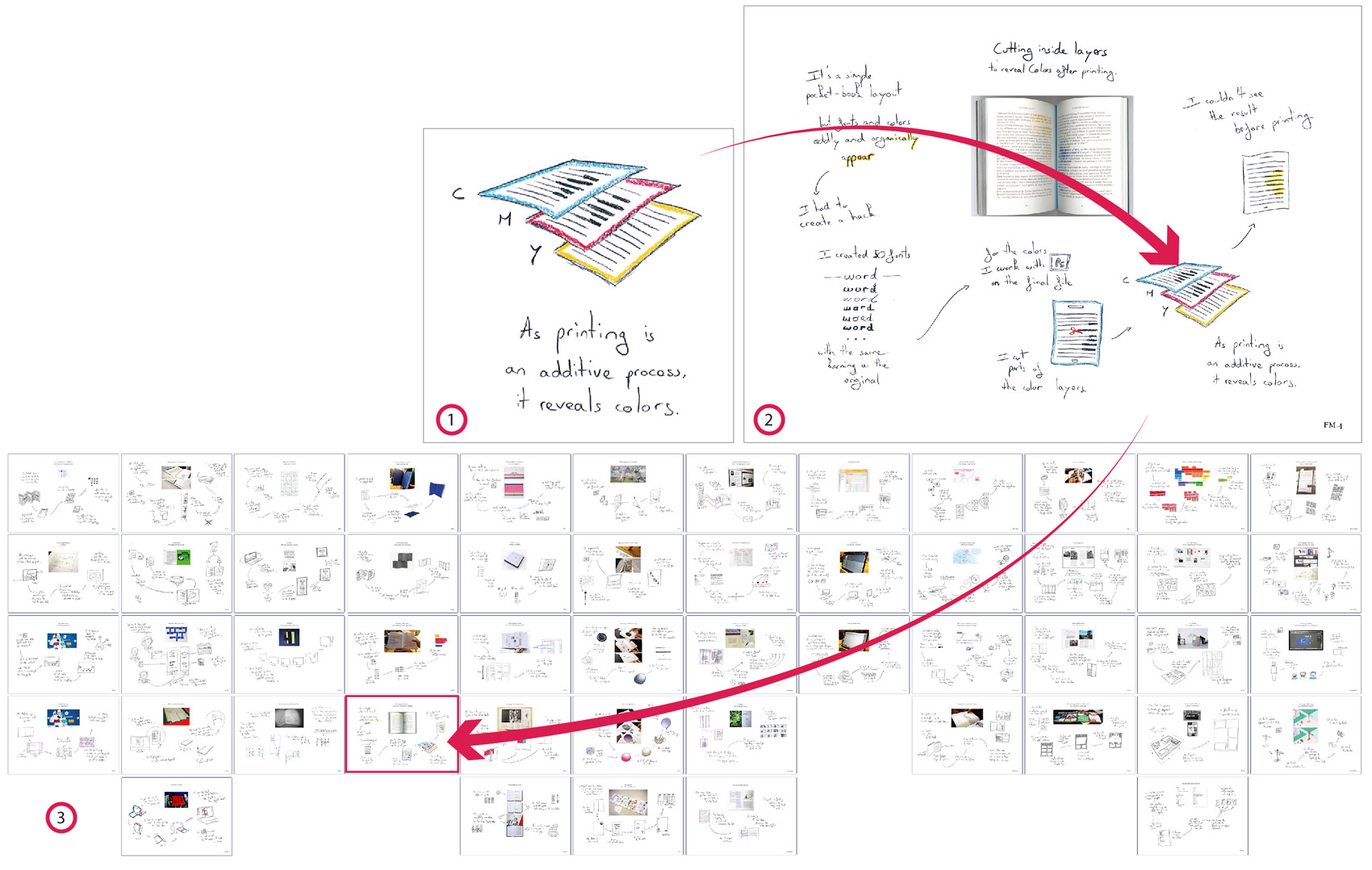

-During a critical object interview, an interviewee demonstrates the different steps in the process, guided by the artifacts at hand.